Engineering can be maddening.

Take for example the challenge I faced some 40 years ago.

Back then, turntables and vinyl were king. There were no CD players, no personal computers. Hell, we made phone calls, wrote letters by hand or knocked them out on a (gasp) typewriter. We had just been wowed by a new fangled invention that could send copies of those letters over the telephone. It was called the Fax Machine.

Heady times, those were.

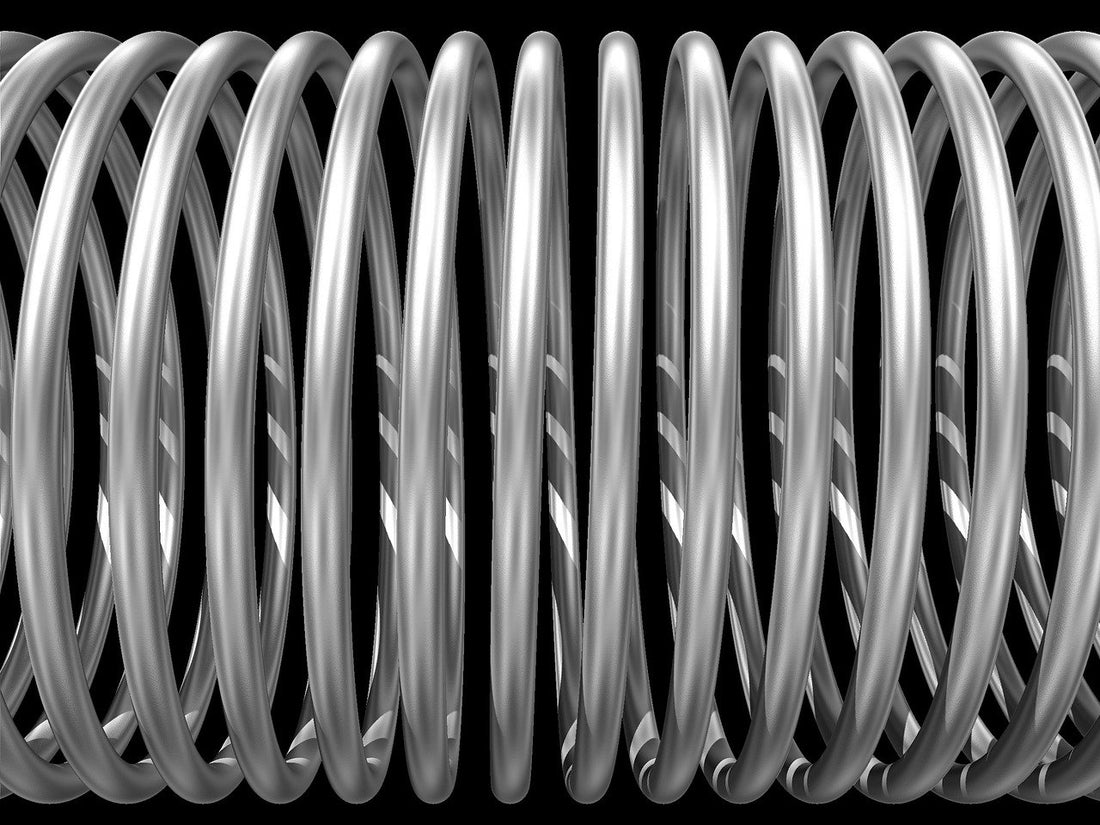

In the late 1970s and into the 1980s the vast majority of vinyl records were scraped with moving magnet cartridges. MM cartridges had been the gold standard for decades. These worked by a simple mechanism: a tiny iron magnet was attached to the end of the cantilever (a small, lightweight rod or beam that holds the stylus (needle) at one end and connects to the cartridge's internal components at the other), and, in close proximity to that magnet, were placed two small coils of wire, one for left and the other for right. When the grooves of the record forced the stylus mechanism to move in concert with the music, the magnet atop the cantilever inched closer and farther away from those coils, generating a tiny voltage which the phono preamplifier boosted loud enough to hear on our speakers. *Which is, of course, where the name Moving Magnet came from.

We engineering types dedicate our lives to pushing forward the state of the art. And, in this case, that state was about to change because of a fundamental problem. The mass of that heavy magnet. Like the mythical full range massless loudspeaker (remember the Hill Plasmatronic speakers?), the best we can hope for in any motion based system is to have zero mass.

No mass, no problem.

But, the world doesn't work that way (let's not get started on Quantum Entanglement which clearly demonstrates we still don't fully understand what the heck's going on). What engineering people do is obey the laws of physics and manipulate them to their advantage. In the case of a phono cartridge, reducing the lumborous mass atop the cantilever would surely have a big sonic advantage. Unfortunately, the lower the magnet's mass the lower it's magnetic field and, thus, the smaller its electrical output (and hence, the lower the volume level coming out of your speakers).

Flip it around.

In the 1950s, two companies—Denon and Ortofon—had been experimenting with building a different type of phono cartridge. This one would place those heavy magnets where the coils lived, and atop the cantilever/stylus arrangement, place a pair of lightweight copper coils. They understood that electrically it doesn't matter if you wave a magnet in front of a coil or the opposite. Coils and magnets moving in close proximity make electrical signals.

They named this type of phono cartridge in the same way the originators of the Moving Magnet chose to call it—by what is moving at the end of the cantilever.

The Moving Coil.

The story continues tomorrow.