Many listeners avoid 20th-century classical music: they associate it with compositions that are aggressive, clamorous, dissonant and, in general, irritating. They don’t like the atonal or 12-tone (dodecaphonic) music that dominated the second half of the century. And they avoid composers who have a reputation for writing “difficult” works. As a result, listeners don’t explore pieces they might enjoy that were written during other periods of a composer’s life, or investigate pieces similar to ones they already appreciate.

To use a hypothetical example from art history: maybe you’ve been avoiding Picasso because you don’t relish paintings from his Cubist period. You might prefer less-abstract works from his Blue Period where subjects are dominated by different shades of blue, or the circus world of his Rose period. Don’t adore any of these? Try the Vollard suite with a Minotaur theme. Don’t like Minotaurs? Consider Picasso’s earliest, most traditional works. If you like those, don’t stop there: try exploring art from his neoclassical period.

Listeners can approach some 20th century music the same way. Composers’ works are often classified into periods and styles, and the few pieces that have become famous don’t necessarily represent a composer’s entire output. The same composer with a “difficult” reputation might have, at a different time, developed musical ideas you would find intriguing, and compositions that are emotionally satisfying.

Prokofiev: Enfant Terrible

Most critics would agree that Prokofiev’s best-known piece is Peter and the Wolf (1936). This composition for children is lyrical and charming, has wide appeal, and has been narrated by a wide variety of people including Jacqueline du Pré, Sophia Loren, Leonard Bernstein, Alice Cooper, David Bowie, Mikhail Gorbachev, Sting, Peter Ustinov, Sean Connery, Lorne Greene, Boris Karloff, and Viola Davis.

In contrast to the likable Peter, Prokofiev was referred to as an “enfant terrible” partly because he was arrogant (he could be rude and insulting, and as a student, criticized others but rejected criticism of his own works); partly due to the spiky, aggressive style of his music. [1] However, Prokofiev wrote in a variety of styles through several periods, culminating in a style that was a blend of traditional tonal and melodic means, dissonant harmonies, aggressive approaches, and the innovations of 20th-century music. Some of the most popular compositions that contradict his “terrible” reputation include Symphony No. 1 (Classical Symphony), Piano Concerto No. 3 (the last movement has one of those lyrical themes that sticks in your mind), Symphony No. 5, the two violin concertos, several ballets (including the often overlooked The Stone Flower), and the Lieutenant Kije suite. [2]

“Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” (audio) You don’t have to be intimidated by Peter’s wolf or 20th-century music. Prepare for your encounters by smiling along with Barbra Streisand’s rendition of “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” from her first LP, The Barbra Streisand Album (1963).

Symphony No. 1 (video) Paavo Järvi conducts the very classic and melodic “Classical” Symphony No. 1 with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

Piano Concerto No. 3 (video) This video was recorded at the Singapore International Piano Festival in 2018 in front of an ecstatic audience and featuring a fabulous, percussive performance by pianist Martha Argerich. Don’t miss this one!

Violin Concerto No. 1 (video) Midori performs an exciting, dramatic, and colorful interpretation of the composer’s first violin concerto. And, if you enjoy hearing where our new artists are coming from, check out Gil Shaham playing the same composition with the National Youth Orchestra 2 (NYO2), an orchestral training program for talented young instrumentalists ages 14 – 17 created by Carnegie Hall’s Weill Music Institute.

Stravinsky: Madman

During its 1913 premier, The Rite of Spring caused a riot. Puccini later called the ballet “the work of a madman” and an anonymous writer expressed a similar opinion in a letter to the Boston Herald:

Who wrote this fiendish Rite of Spring,

What right had he to write the thing,

Against our helpless ears to fling

Its crash, clash, cling, clang, bing, bang bing?

And then to call it Rite of Spring,

The season when on joyous wing

The birds melodious carols sing

And harmony’s in everything!

He who could write the Rite of Spring,

If I be right, by right should swing!

If you’ve avoided Stravinsky’s music based on this ballet, you’ve missed many works you might enjoy. The Rite doesn’t have much in common with compositions from other periods of his life (Stravinsky said it “was guided by no system whatever”) and he is, in fact, considered to be a neo-classic composer. [3] Stravinsky’s two other early ballets for ballet impresario Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes (The Firebird and Petrushka) are colorful and melodic, closer to the Romanticism of Stravinsky’s teacher Rimsky-Korsakov than the “crash, clash, cling, clang, bing” of his third ballet.

Stravinsky’s works are characterized by their unique timbres, constantly shifting rhythms, lean orchestrations, dissonant harmonies, and cool detachment – a style that influenced the way later composers used rhythm and form. Stravinsky’s last period consisted of dodecaphonic works that, despite being based on atonal 12-tone techniques, still sound like Stravinsky.

Recommended compositions: Pulcinella (ballet), Oedipus Rex (oratorio), Les Noces (based on the texts of Russian village wedding songs), Symphony of Psalms (choral symphony), the jazzy and rhythmically driven Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra, The Soldier’s Tale (mixed media – considered avant-garde at the time), The Rake’s Progress (a mock-serious pastiche of late 18th-century grand opera), and Symphonies of Wind Instruments.

Capriccio for piano and orchestra (video) A terrific performance of the “Rubies” portion of the Jewels ballet choreographed by George Balanchine and danced here by Diana Vishneva.

Circus Polka for a Young Elephant (audio) Elihau Inbal conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra in a piece written for the elephant ballet of the Barnum & Bailey’s Circus. The piece was later choreographed by Balanchine.

Symphony in Three Movements (video) Recorded at Skidmore College’s Mostly Modern Festival, this is a sharp, driven performance that sounds even better than some of the “name brand” recordings.

Maurice Ravel: The Great Impressionist

Whether you’ve heard it in the film 10 or someplace else, most listeners are familiar with Bolero. Ravel, however, wasn’t a fan of his own composition: He considered it trivial and once described Bolero as “a piece for orchestra without music.” [4] Ravel said:

“It constitutes an experiment in a very special and limited direction, and should not be suspected of aiming at achieving anything different from, or anything more than, it actually does achieve. Before its first performance, I issued a warning to the effect that what I had written was a piece lasting seventeen minutes and consisting wholly of ‘orchestral tissue without music’ – of one very long, gradual crescendo. There are no contrasts, and practically no invention except the plan and the manner of execution.” [5]

Bolero, originally a ballet score, is much more accomplished than Ravel’s warnings imply. If you watch and listen closely you’ll find rich sounds, constantly changing dynamics, and a variety of wonderful orchestral colors while the musicians practically dance to the music on the way to its conclusion.

Ravel and Debussy were the defining composers of Impressionism and many critics claim Ravel was influenced by Debussy. However, Ravel claimed he was much more influenced by Mozart and Couperin (whose compositions are very structured) and influenced by world music including American jazz, Asian music, and traditional European folk music. In keeping with the French school of music, Ravel’s melodies are almost exclusively modal instead of using major or minor scales.

Recommended compositions: Like The Rite of Spring, Ravel’s Bolero is an anomaly. There’s a wide variety of other compositions to enjoy including: the impressionistic ballet Daphnis et Chloé, suites (e.g., Ma mère l’oye), one-movement dance pieces (e.g., La valse), re-styled dances (e.g., Pavane pour une infante défunte and Le Tombeau de Couperin), the captivating Piano Trio, two jazzy piano concertos (including the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand), several short orchestral pieces like La Valse, many piano works, the violin sonatas and, of course, the beautiful Schéhérazade with orchestra and vocal soloist. [6]

Bolero/Lorenzo Viotti conducting the Münchner Philharmoniker (video) Expressive players and conductor, a sharp performance, and some nice scenery make this video special.

Daphnis et Chloé/Charles Munch conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra (audio) A classic, lush-sounding performance from the RCA Living Stereo series. This is often considered to be the best-recorded version.

Daphnis et Chloé/Pierre Boulez conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (audio) Not enough time to listen to the complete ballet? Start at the end (“Troisième partie – Danse générale”) with Pierre Boulez conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in a transparent-sounding and exciting performance.

Piano Concerto in G Major/Philippe Jordan conducting the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester with Jean-Yves Thibaudet, piano (video) Jazzy outer movements with a tranquil second movement and superb performances by all.

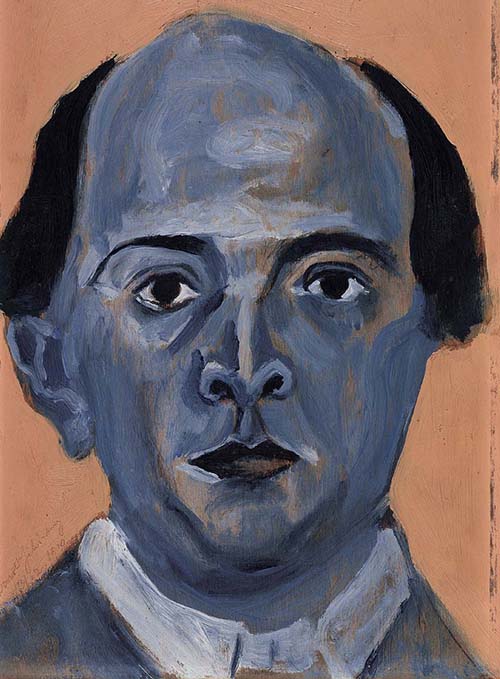

Arnold Schoenberg: The Revolutionary

Read the name Arnold Schoenberg and 12-tone music comes immediately to mind.

Schoenberg’s 12-tone method of composition grew out of post-Romantic music that had become extremely complex with huge blocks of sound. Convinced that this music couldn’t develop any further, he started composing using atonal motifs. This led to organizing notes into rows of 12 without relationships to each other and without tonal centers, a composition technique Schoenberg viewed as revolutionary because it was different from any music previously composed.

During the composer’s pre-revolutionary period, he wrote the symphonic cantata Gurrelieder for five soloists, narrator, four choruses, and large orchestra that pushed chromatic writing to extremes but was still within the limits of tonality. It’s engrossing, sometimes moving music that can be especially appreciated by listeners who enjoy the large works of Richard Strauss (before he reverted to a more conservative style), Mahler, and Wagner. The other work suggested below, Verklärte Nacht (in its original string quartet version) is lyrical and expressive without a tone row to be found.

As the old Alka-Seltzer ad said: “Try it, you’ll like it.” If you do like it, you might want to explore some of Schoenberg’s other early and transitional works.

Gurrelieder Part 13: “Waldemar: Herrgott, weisst du, was du tatest”/Riccardo Chailly conducting the RSO (audio) This is the best performance on CD and has the best sound, spoiled somewhat by a change of perspective from disc 1 to disc 2.

Verklärte Nacht/The Quatuor Ebène (with additional players) (video) A terrific quartet playing a listener favorite, usually heard in its orchestral version.

John Cage and the Sound of Silence

Cage’s most (in)famous musical composition is 4’33″, which refers to four minutes and thirty three seconds of silence. It can be performed any time. Any place. By any number of people. It doesn’t even have to last for four minutes and 33 seconds because there isn’t an indication in the score of how long a performance should be. 4′33″ was first performed in 1952 and quickly became controversial because it consisted of silence or, more accurately, ambient sounds – what Cage called “the absence of intended sounds.” Sounds like a cough during a concert. The rustle of a paper program. The air conditioning. A member of the audience shifting in his or her seat. The sound of a musician’s foot moving on the stage floor.

Cage’s early period involved writing dodecaphonic music in the style of his teacher Schoenberg, but by 1939 he had started to experiment with unorthodox instruments to go beyond conventional Western music. He invented the “prepared piano” by placing pieces of chalk between the piano strings to create special effects, [7] and eventually regarded all kinds of sounds as musical. Cage encouraged audiences to focus on all types of sonic phenomena rather than just those elements chosen by a composer, and pioneered “indeterminism” in his music. To ensure randomness and eliminate any element of personal taste on the part of a performer, he used a number of devices including unspecified instruments and numbers of performers, unfixed duration of sounds and entire pieces, inexact notations, and sequences of events determined by random means.

Cage was one of the most influential composers and theorists of the 20th-century and changed the way people think about music. You can read more about Cage in his two books, Silence, and A Year from Monday.

4’33″/Kirill Petrenko conducting the Berliner Philharmoniker (video) One of the world’s greatest orchestras plays silently, and the site includes some entertaining YouTube listener comments.

Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano/Maro Ajemian, piano (audio) A sample of Cage’s non-traditional sounds incorporated into his compositions.

[1] Prokofiev graduated from the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1914 with performance degrees in piano and conducting, and won first prize at his exams by playing his own Piano Concerto No. 1 (1911). His second piano concerto (1912), as clangorous and dissonant as the first, helped establish his reputation as an enfant terrible.

[2] Prokofiev and Stravinsky were friends although Prokofiev didn’t enjoy Stravinsky’s later works. Stravinsky modestly described Prokofiev as the greatest Russian composer of his day, after himself.

[3] Neoclassicism was a twentieth-century movement especially popular during the interwar period. Composers who were part of this movement sought a return to aesthetic principles associated with the concept of “classicism,” namely order, balance, clarity, economy, and emotional restraint.

[4] New World Encyclopedia

[5] From a newspaper interview with The Daily Telegraph in July 1931.

[6] Not to be confused with the equally beautiful Scheherazade by Rimsky-Korsakov.

[7] Don’t try this at home, especially with cured meat.

Header image: Arnold Schoenberg, self portrait, 1910.