The glam metal era is loaded with memorable personalities from heroic acts including Poison, Mötley Crüe, Ratt, and more. But peel back the onion, and layers of incredible music teeming with vivid creativity are yearning to be rediscovered.

While Neverland wasn’t exactly a prototypical 1980s – 1990s glam metal band, they’re often lumped in with the era just the same. And though they’re most known for the track “Drinking Again,” which was included on the Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure soundtrack, in reality, the music of Neverland presented as a stark alternative to much of the FM radio fodder of the day. (They should not be confused with the Japanese band of the same name and era, or today’s Neverland country/rock/metal band from San Jose, California.)

At the forefront of it all was front man Dean Ortega, a thinking man’s rocker with sensibilities deeply rooted in AOR rock music and classic Disney films, of all places. Sadly, through shifting tides and shoddy dealings, Neverland never got its due, and before it was over, Ortega jettisoned himself for projects anew.

In the years since, Ortega has been a rover, still making music through various projects but mainly focusing on family life. With aspirations of raising children taking priority over the perilous rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle, Ortega keeps things simple these days, making the music that speaks to his soul through his band, Revolution Child.

In this rare career-spanning interview, vocalist and guitarist Dean Ortega runs through the hard-luck story of Neverland, one of many rock bands that should have made the big time, but had it slip away.

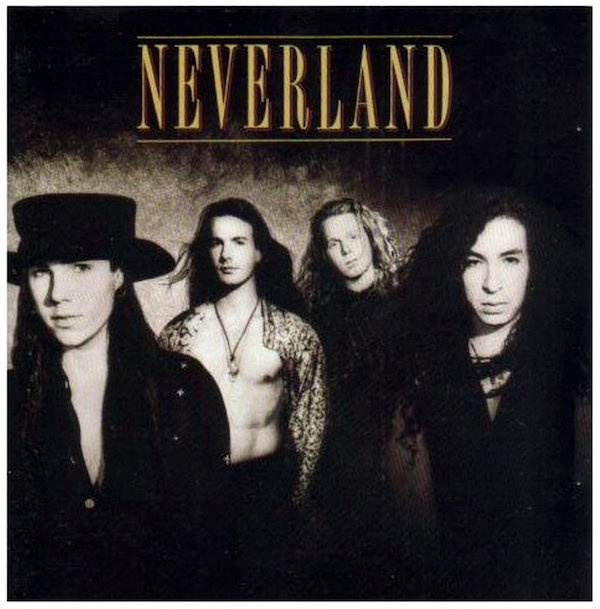

Neverland, album cover.

Andrew Daly: What first drew you toward rock music?

Dean Ortega: According to my mother, at the age of three, I pulled out all of the pots and pans in the kitchen and started pounding away on them to my favorite Beatles songs as if they were drums. From that point, I never looked back.

AD: Who were some of your early influences who shaped your vocal style?

DO: As a young child, I loved Disney movies. There was one movie that really got my attention, The Jungle Book. It was the song “I Wan’na Be Like You,” sung by the late great Louis Prima. His voice was so rich with character and confidence. It was undeniable that this is what got me singing, then followed by the Beatles, Jan and Dean, the Beach Boys, Three Dog Night, Harry Nilsson, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, and Iron Maiden.

AD: Growing up in California, paint a picture of the scene that shaped you.

DO: I was 12 and loved living in Whittier, California. It was a great place to grow up, besides living in a household that was very supportive of the arts. There was music everywhere around my neighborhood, a lot of rock bands that would rehearse in their garage-converted studios. Back then, you could pound on the door, and most of the time, they would welcome you with open arms and let you watch them practice.

At the time, I was a drummer, so all I wanted to do was learn as much as possible about the drums. At 12, I started a band; as time went on, I ended up playing with a few different bands, and it was all about the backyard parties in the Whittier, La Habra, and La Mirada areas. I played every weekend, just worked on my craft, and had a great following.

At the ripe age of 15, I had my first real Hollywood showcase at Gazzarri’s; my mother had to chaperone the band after she convinced Bill [Gazzarri] it was a great idea to let my underage band play there on a Sunday night for a battle of the bands. The winner got to play a regular spot on Saturday nights. We won, and that led to other opportunities all around the L.A. nightclub scene. After a few years of drumming [and] singing, I decided to dedicate myself to vocals, and since I couldn’t really write songs without an accompanying instrument, the logical one [to take up] at the time was the acoustic guitar.

AD: Walk me through your initial interactions with guitarist Patrick Sugg.

DO: [By] this time, I had played with a lot of really good bands around the Hollywood circuit: The Answer, XL, and Lace. But it was The Rozy Crucifixion that got the attention of Hector Sanchez, the A&R rep from Virgin Records, who brought me to A&M studios to meet [producer] Jimmy Iovine one afternoon. After sitting and talking about music in-depth for a good while with Jimmy, he asked me to play a song on the spot. Later, he told me, “The reason I wanted to work with you was because you were prepared.” Being prepared was the key to success. In other words, if I didn’t play the guitar and sing that day for him, he would have passed on me. So, thank God I was ready, and he liked what he heard. (laughs)

He then decided to play me a song by an up-and-coming young guitar player called Patrick Sugg, who he thought might be a good fit to collaborate with. After listening to the song, I was still not convinced. Although the guitar was great in the song he showed me, I still was hesitant about doing this because I was loyal to the guys in my band. After a week of considering meeting with Patrick, my manager, Cathy Pedley from Rozy Crucifixion, convinced me I should check it out. She said, “This could be the break you’ve been working so hard for. The guys in Rozy are your true friends, and they’ll understand.”

AD: Was the chemistry with Patrick immediate?

DO: Well, I can tell you this, I met with Patrick, and from then on, we were inseparable. We met every night at Jimmy’s office at A&M Studios at about 6:00 p.m. when the offices closed. And once we were there, we would write until early the next morning when the offices would open. It was unbelievable how easily the songs came, and we did this for months until Jimmy said, “You’re ready to demo some of your songs.” And just like that, he called on seasoned session players to play on our demos, but they were much older than us, and we didn’t have much in common with them. But the best part of this was we got to record all our demos at the best recording studio in the world, A&M. It was a dream come true.

AD: How did bassist/vocalist Gary Lee and drummer Scott Garrett enter the picture, leading up to the formation of Neverland?

DO: After we finished the demos, Patrick and I wanted to find the right players for the band, so the search went on for a long time before we found the right guys. During our demo sessions at A&M, Gary Lee was doing a recording session there with Rudy Richmond, the drummer from the Quireboys. This is where our paths crossed; at the time, we didn’t have a solid drummer yet, but we still invited Gary in for a jam, and he fit in perfectly – with his great backing vocals and superb bass playing, we could not let him slip away. We continued to play with many different drummers, but Patrick and I were still not satisfied with any of them.

Finally, one late night, Patrick and I were working on a song called “Time to Let Go,” we were rehearsing at the famous Gardner Studios behind Guitar Center on the Sunset Strip. [Producer] Chuck Reed acquired [the studio time] for us. And lo and behold, we hear a lone drummer practicing on the other side of the studio wall. We had never heard anybody in this other room in the past, and we had no idea there was a room there. We listened to this drummer with killer chops and meter, and we both thought, “This is the guy.” But now we had to figure out how to convince him to come and play with us. After pounding on the wall for what seemed like forever, Scott finally heard us, and we asked him to jam right then and there. He came over, and we hit it off right from the get-go, and thus Neverland was born.

Neverland: Gary Lee (bass), Dean Ortega (vocals), Patrick Sugg (guitar)and Scott Garrett (drums).

AD: What do you recall regarding Neverland’s first gig and subsequent rise on the club scene?

DO: Neverland’s first show was at the University of Santa Barbara in the quad at 1:00 p.m. It was good, but no one knew who we were. We had a good response and got asked to play at other local bars on Main Street a few times after that show. The crazy thing about Neverland was we really never played the [Sunset] Strip a lot, we played at Club Lingerie a few times in L.A. and one time at the Troubadour, but that was really about it as far as Hollywood goes.

Jimmy had other plans for us: he put us on a small club tour through the US for about three months with a band called Blonz, a band from the Midwest. He wanted us to [get some experience in to] tighten up the set. We then went on the road with The Divinyls for a while, then went to the East Coast, where we opened for Kix for about two months, getting better and better. Finally, we landed an arena tour with the Moody Blues, and that’s when we felt like we had arrived.

AD: As a late 1980s-era signing, what allowed Neverland to stand out amongst the many bands vying for time in front of record executives?

DO: I think Neverland stood out because we were not a heavy metal hair band from the ’80s; we were more like an AOR [album oriented rock] band. We were more like our heroes from the ’60s and ’70s with depth in our songs, not just the run-of-the-mill sex, drugs, rock and roll clichés. Don’t get me wrong; it’s not that I didn’t like that music; I actually love that stuff and still do to this day. But I felt like we made it a point to be conscientious and try to write songs with a bit more depth. We wanted to write about our experiences from life itself, and we wanted to be as original as we possibly could. It was important to us to try not to sound like anybody but ourselves.

Click here for a Neverland Spotify playlist.

AD: What made Interscope Records the right label for Neverland?

DO: Well, let’s face it, who knows what the right label is for anyone? At the time, we tried our best to make the right decisions. Interscope Records had a huge buzz. It was all about this up-and-coming label that was to be headed by Jimmy Lovine and Ted Fields, two of the biggest heavy hitters on the planet. [Interscope was founded in 1990 – Ed.] They covered a lot of ground when they decided to combine the music and movie industries. Not to mention, after all that Jimmy did for us at the beginning stages of the [earlier] A&M days, we felt it would only be fitting to give him first dibs at the band since he was so good to us. We also had a great lawyer at the time, Bill Coben, and he wouldn’t take “no” for an answer, and the bidding wars were long and drawn out. At the end of the day, he got us everything we could ever want from a label, so of course, it had to be Interscope Records.

AD: Can you recount Neverland’s process while recording its self-titled debut?

DO: Before we met Scott and Gary, Patrick and I had already written most of the songs. Once they joined the band, we started writing more fluently; since we had an actual band to work with, we could now add more aspects to the instrumentation of each song. Not to say they didn’t help in the arranging process, but for the most of it, Patrick and I would bring in our ideas, and we would work them out together first, then bring them to the band, and the band would develop the finished product.

As far as the recording of the album goes, once we figured out what songs to record, we had to find the perfect producer that we could all agree on. We met with several producers: some of the producers that were up for the task were Todd Rundgren, Steve Mac, Peter Frampton, Mutt Lange, Beau Hill, Paul O’Neill, and Bob Rock, to name a few. But Tim Palmer had the credentials that seemed to be the perfect fit for what we were looking for sonically overall. Thank God he liked our music and, like us as a band, he was great to work with.

If you think about where the band was at this moment in our career, we had just signed an incredible deal with Interscope Records, probably one of the biggest ones at the time, [and] we were so high on life, that poor guy had his work cut out for him. If Tim knew what was going to happen in the next few months, I don’t know if he would have taken this one on. (laughs) We set up everything so it could be recorded as live as possible; the band played together on all the tracks, then we would go back and fix things we didn’t like and add new ideas to each song. It was like painting a portrait of our lives. After it was all said and done, all I could say was [making the album] was a wild time at A&M Studios, but by the end of the day, we worked hard at getting things as close to perfect as possible.

AD: Despite the additional publicity from the inclusion of “Drinking Again” on the Bill and Ted Soundtrack, Neverland’s debut failed to hit. To what do you attribute the lack of attention?

DO: Well, considering the timing of our release, I feel we got lost in the shuffle. The [newer] technology of the music industry and social media was on the rise, not to mention the [then] new grunge scene was beginning to take over the airwaves, so yeah…a lot was going on at that time. The label was [trying to figure] out the next big thing and where we would fit in. So yes, I feel like they didn’t really know where we would integrate and how to properly place us in front of the right audience. It’s hard to say if Interscope properly supported us, but looking at it now, I feel like they were such a new label at the time; I think they were still getting all the right pieces in order as our record was released at the same time.

AD: Did it bother you that Neverland was lumped in with the glam bands of the era?

DO: Yes, this is true, we were lumped in with the glam pop band category, but I never felt we were that type of band at all. I mean, let’s face it, glam bands are bands like Hanoi Rocks, Poison, and Enuff Z’Nuff, which are all great, but we were nothing like those bands. It’s all about the overall sound of our music. Although our music was catchy, it wasn’t glam rock. We felt like we had no limits to our style of music. We wanted to bring all type of cultures into our music and try and filter it with the Neverland signature sound. So yes, in answer to your question, we were equipped to navigate through any changes that lay ahead.

AD: What led to you leaving Neverland in 1993?

DO: We started writing for the new record, and clashing personalities and egos got the best of the band. I didn’t really like the direction the band was headed, so I spoke to my manager Tom Hulett, one of the best managers at that time, and told him I was unhappy with the band and that I was going to leave and start a new project. He was very supportive and said he would remain my personal manager and help get me where he felt I should be at this point in my career. Unfortunately, tragedy struck, and Tom suddenly died. It was devastating; he was basically like a father figure to me. We were very close, and I didn’t want to continue after that, so I went on a hiatus for the next few years. Let’s just say you don’t know a person till you live with them for several months on a bus.

AD: How did you subsequently become involved with (Latin rock band) Tribe of Gypsies?

DO: Well, that came about through a mutual friend, a rock magazine journalist named Chris Leibundgut. He had interviewed me earlier when I was in Neverland, called me out of the blue, and said, “I have the perfect band for you. Man, you have to come to their rehearsal and check them out.” At the time, I was starting an early version of Revolution Child, writing with many different bands and doing studio work. I wasn’t interested in putting more on my plate at the time, but Chris wasn’t going to stop until I met with them, so we planned and went to see a rehearsal, and all I could say was it was magic from the minute I walked in.

I sat for about 10 minutes and immediately found myself engaged with the sound of the band and jumped right up and grabbed a mic, and started singing the first melodies and words of the song that turned out to be “We All Bleed Red.” From that point we all looked at each other and knew it was inevitable what was going to happen next. It was so easy to write music with those guys. The band appeared to be unstoppable, but [like] all things in life, nothing lasts forever.

AD: After releasing the second Tribe of Gypsies album, in fact titled Nothing Lasts Forever, how did you ride out the remainder of the 1990s?

DO: After the whirlwind of Tribe of Gypsies, from late 1995 till 1998 I continued to write music with several different artists and had just started toying with the idea of Revolution Child. But at that moment, I felt the clock running out [for wanting] to start a family. I always wanted to have kids [while I was] young enough to enjoy them, so my wife and I decided to start a family in 1999, and from that point on, it was all about family. Don’t get me wrong, I still had my music and played a show occasionally here and there, but I was and still am enjoying being a dad and dedicated the next several years to that.

AD: The Answer was a solid return to the scene for you with an early version of Revolution Child. How did the band get its start?

DO: Thank you. The Revolution Child lineup was De Autry Jones II on bass, keys, and backing vocals (a phenomenal musician) and Ron “stone groove” Thomas on drums. We later added Mike Thomas on guitar and backing vocals. Revolution Child was formed organically and was not premeditated at all. It was just a weekend jam session for a while, but then it started to gain momentum, and a great guy named Jon Sutherland (music journalist/music buff/manager) got wind of the project and said we should record an album.

Revolution Child: De Autry Jones II, Ron Thomas, and Dean Ortega.

So, we did, and Jon executive-produced it, and it was brilliant; he really helped us a lot. Revolution Child wasn’t just a band, but a brotherhood of great individuals who liked each other and worked well together. We could jam like no one else; it was as if we knew every next move before it even came out. We could write songs on the spot live on stage, and the best part about it was the fans would never know. They would ask after the show if that was a new song, and we would tell them, “no, we just made it up. I hope you liked it because it may never come back the same way you heard it.” (laughs)

AD: Fast forward to the present day. What led to the reformation of Revolution Child?

DO: Well, it all started again when an old friend of mine, Dan Sindel, reached out to me and asked if I wanted to start a cover band with him and a few of his friends. I told him I wasn’t interested in starting a cover band, but he was persistent and said it was only a jam session. I finally agreed to come by and jam, but I got bored doing covers as time passed. So, one day after a session, I talked with the bass player and drummer, and we started talking about our musical past and I showed them Revolution Child’s The Answer.

As it turns out, they instantly loved it, and we decided to give it a go. The result was overwhelming, with good energy. From that day forward, we started writing new songs and never looked back; thus, a new lineup was born – Hector Chaparro on bass and backing vocals and John Licali on drums and backing vocals. Since the new lineup has come together, we’ve produced and released two new tracks, “Delusional Life” and “Venom,” with plenty more to come. We plan on doing a few live streams and playing a few selected venues in the near future.

AD: You seem to be as creative as ever. What’s next?

DO: I’ve been wanting to release some solo acoustic stuff that’s been sitting on the back burner for way too long, so look out for that stuff soon. I want to continue to play as much as possible, write as much as possible, and feed my soul with the passion of music until I die.

All images courtesy of Dean Ortega.