An Individual Approach to Computer Audio

Mention the words “computer audio” and it is likely to mean different things to different people. To traditional audiophiles, it could mean convenient access to their music collection, be it ripped CDs or streaming, while ultimate-performance enthusiasts would naturally marry high-resolution formats with the latest DAC technology. The younger generation may be drawn to the user-friendly way of enjoying music from a familiar smartphone interface. Computer hobbyists can find an additional way to enjoy a favorite pastime via high-res music listening, and specification enthusiasts can indulge in a race to the next dB.

The good news is that the

hobby of computer audio can provide enjoyment to more people than just traditional audiophiles, and in more ways than before. A larger market results in greater variety and better-quality products at better prices, and that is good for audiophiles. The current availability of a wide range of quality DACs at the $1,000 to $2,000 price point is an example.

Chord

Qutest DAC, US$1,695 from various retailers.

However, computer audio has also brought a hornet’s nest of sometimes complicated hardware and software setup requirements, (sometimes unnecessary) jargon, and wildly differing and often less-than-helpful advice. Plenty of arguments on chat groups lead nowhere, and many need attention from the moderator. There was less “noise” in the heyday of vinyl, when audiophiles had more consensus on the direction of how to achieve the best sound from records, and what was necessary to get there. Back then it was possible for a dedicated audiophile to audition most of the leading sources, amplifiers and speakers, and in the most effective combinations, and this carried over to much of the CD era.

In the world of computer audio, the greater complexity means that there are simply too many variables for even the most dedicated enthusiast to be an expert on everything. No one can possibly try every type of software, computer, DAC, LAN switch, cable, power supply and so on and in all possible configurations. Even a conceptually simple test between any of these can be hard to arrange, and A/B comparisons are either hard to do or impossible. For example, how would someone compare the sound quality of Tidal via two different internet service providers feeding the same hi-fi system in the same room?

In a world where no one has the same goals, systems or circumstances, then everyone is right, because they have figured out what works for

them. It is my belief that in the era of computer audio, the audiophile must march to his or her own beat, so if you disagree with what I am writing, good for you!

Objectives

Why consider computer audio? Many if not most

Copper readers are experienced audiophiles with a good sounding high-end system that represents a significant investment in time and money. Equally important, readers already possess the most important measuring instrument – a trained set of ears.

Some may be interested in an easy way to add streaming audio to an existing system, while others may want to go all-in and retire the CD transport, and still others may want to move towards a whole-house network setup with different systems for different music or rooms.

The desired level of technology involvement is a consideration. One should be able to enjoy computer audio without having to do computer engineering. Yet if computer engineering is your thing, then why not? This is, after all, a hobby, and if someone says you are wasting time assembling Raspberry Pis but that is what you enjoy, then you know what to do. Already we can see there is not going to be a one-size-fits-all solution.

My basic philosophy is to do what is right to maximize your own enjoyment. To make the hobby sustainable, my belief is that one should aim to retain as much of their existing system as possible. Incremental rather than wholesale changes are preferred, so that progress can be made in a step-by-step rather than a random fashion. In this article, I would like to discuss some common considerations based on my own experience.

A Personal Note

I may be the luckiest audiophile in the world. On a given day I could be treated to a Chopin Nocturne played on a Steinway Model A. How about a Bach Cello Suite played on an 1840 Kennedy cello? Maybe a Salzedo tango played on a Lyon & Healy concert grand harp?

All this right in my own lounge. You see, my family members are gifted musicians and there is often live music in the house. The experience of a concert instrument unleashed at close range is astounding – once heard, it is hard to view recorded music in the same realm.

But live music in an ideal setting does not happen on demand. I also like a variety of genres, composers and artists. Like many UK audiophiles, I spent too many evenings tuning my Linn Sondek turntable to sound euphoric on a small selection of records (in reply to my good friend Dr. Adrian Wu). Imperial College, where I studied electrical engineering, had an active audio society. Manufacturers such as Meridian, Naim and Dynavector would come to demo their equipment. They must have thought we had good ears because as students we certainly did not have good credit.

When CD arrived in 1982, it did not deliver “perfect sound forever” but it did bring the enjoyment of convenience that enabled each listening session to have more music and less fiddling around. (I concede that some folks prefer to fiddle around and that’s fine.) As CD sound quality improved over the years, it brought a welcome level of consistency and enjoyment across genres. I began to buy CDs exclusively but kept my Linn.

iTunes: the First Popular Computer Audio

In 2005, along with my first iPod came my interest in iTunes which, for me, was a defining product in computer audio. iTunes was not intended to be a high-end product and its sound quality was sufficient only for casual listening, but for the first time, I could easily browse my entire CD library and find any track by artist, album or song. Whereas before I felt I did not have enough CDs and often struggled to find something to listen to, now the effect was like having a larger library at no additional outlay. I transferred my entire CD collection to the computer in lossless formats and since I kept my originals, I could use the CD transport whenever better sound was required. But, I thought, what if there could be an iTunes with sound approaching or even comparable to a CD transport?

High-Resolution Computer Audio Software

Bit-for-bit computer audio software such as the

JRiver Media Center (PC) and

Audirvana (Mac) promises to combine iTunes-like easy browsing with much improved sound quality. They were easy to set up and operate – if you could install Word, you could handle JRiver. When I changed to JRiver in 2010, computer audio sound quality was some way below a CD transport, but the combination of an entire music library controlled from the listening chair and with good enough sound quality was persuasive.

JRiver had two key audiophile features. Memory playback involves the pre-loading of an entire track from a hard drive to semiconductor memory before the first note is played. Many things happen when music is read from a disk drive. The disk spins to the angle where the track is stored, powerful motors move the magnetic heads to the correct position, and the data is read, checked for read errors and re-read if necessary. With so much going on, some audiophiles could even hear differences between different models of hard drives. With memory playback, however, the computer merely needs to feed the track from memory to audio hardware during playback. By decreasing the work performed in real time, the sound quality could be improved.

JRiver could send the audio data directly to compatible audio hardware – at the time often a professional sound card such as a

Lynx or

ESI – via a technology used in studios called ASIO (Audio Stream Input/Output) that gave much better sound because it bypassed Windows’ multiple layers of audio processing. Microsoft’s more recent WASAPI tries to do the same thing but does not sound as transparent in my experience. With user-friendly bit-perfect software like JRiver, computer audio began to gain traction.

Building a Music Library

The availability of a digital music library is, of course, critical. Most audiophiles have hundreds of CDs or even thousands, so this can form a good basis. Transferring (“ripping”) CDs to a computer for personal use is legal and accepted (see

About Piracy - RIAA).

Exact Audio Copy is a popular software utility (see

Tom Gibbs' article in Issue 143), and, for whatever software you might decide upon, a lossless audio format, usually FLAC or AIFF, should be chosen. The software should be set up to automatically fill in the fields for artist, album, track and genre by matching the CD with an online database (the computer needs to have internet access during ripping), but manual editing is sometimes required. Ripping 1,000 CDs sounds daunting, but it is not that hard once you set up a production line.

One can of course also purchase tracks, albums and entire libraries online, and some of my favorite albums are now available in hi-res. However, I think there is something wrong with having to purchase the same music three times – the first time for vinyl, the second time for CD and now for hi-res, so I have kept my purchases to new releases.

Nowadays, by far the biggest source of music for computer audio is hi-res streaming. I am a fan of Tidal HiFi because it caters to my musical tastes (classical and jazz) and the audio quality is excellent. If Tidal suits you, there is no need to rip your CDs. Simply take out a subscription to

Tidal HiFi and enjoy a library of 60 million tracks at CD-quality or better. Tidal hi-res is streamed in MQA format and my experience has been very positive. The big announcement in hi-res streaming this year (2021) was the availability of Apple Music in hi-res, and audiophiles will need to figure out how best to use it and whether it has competitive sound quality.

USB DACs

Computer audiophiles have long recognized that computers are bad places in which to put audio hardware such as DACs. The inside of a computer is an extremely noisy electrical environment and the switching power supplies are designed for electrical efficiency and not sound quality. A few manufacturers have made efforts to design audiophile sound cards but with mixed results.

When high-end USB input DACs became available that allowed computer audiophiles to move the DAC outside of the computer, sound cards went out of fashion overnight. USB DACs further improved once engineers figured out how to turn what is basically a dirt-cheap data link into a high-end interface. Nowadays pretty much all USB DACS use asynchronous transfer, which improves sound quality by increasing the isolation between the DAC and the computer.

Directly Connecting a Windows or MacOS Computer to a DAC

At this point, we have a PC or a Mac running bit-perfect software directly connected to a USB DAC. Sound quality has improved but it is probably still way below a CD transport. Why is that?

If you open Task Manager on a PC or Activity Monitor on a Mac, you will see its doing hundreds of tasks at the same time. All those tasks enable office workers to get their documents done, work-from-home folks to do video conferencing, students to research their homework and everyone else to watch YouTube and play games at the same time. Very few tasks have anything to do with audio, and every unnecessary task is detrimental to sound quality because it makes the computer work harder for no gain. How can Windows or MacOS possibly compete with a dedicated CD transport that is designed specifically for music playback?

You could try using “optimizing” software that streamlines Windows or MacOS by shutting off some unnecessary tasks. But shut off too many and the computer stops working. It is simply impossible to turn Windows or MacOS into something they are not.

Running hundreds of concurrent tasks requires powerful processors. Look under the hood of any recent computer, even a laptop, and you will see at least a quad-core processor that uses so much power it needs fancy cooling. All that power is consumed by billions of transistors switching on and off at mind-boggling speeds. Imagine 30 billion tiny light switches inside your computer flipping on and off three billion times a second, happily generating electrical noise and RF interference.

Audiophile Computers

If you must use Windows, you can consider an “audiophile computer.” Potential European suppliers include

Audio PC Shop and

Pachanko Labs, and some suppliers use chassis from a company called

HDPLEX.

Some argue that equipment upstream of an asynchronous USB DAC cannot affect sound because bits are bits. As audiophiles, you must trust your ears.

Look inside an audiophile computer and you should see a gaming-grade computer motherboard. (The best-quality motherboards are designed for eSports.) The motherboard may have some modifications, such as higher quality clock chips, to make it more suitable for audio. You should find a medium-power processor – appropriate for the job and with reduced electrical and fan noise. Quality solid state drives such Samsung are standard. No audio engineer expects you to drive your high-end DAC from a consumer motherboard so look for a separate audio-grade USB or SP/DIF/AES board. A linear power supply is preferred but adds considerably to the cost. Decent casework completes the picture. If you must use MacOS, your options are effectively limited to Apple’s product line.

With an audiophile computer, sound quality has improved to the limit of what can be done with a computer directly connected to a DAC, but in my experience may still be below what can be heard from a high-end CD transport.

The fundamental problem is that the PC industry does not make computers designed for audiophiles. Development and tooling costs are high and factories are running flat-out, shipping 500 office and gaming computers

every second. To them, the audiophile market is but a rounding error – it does not pay to make computers designed for us. The audiophile computers I see advertised, even those incorporating significant engineering, are still office or gaming computers at heart. (There is a better place for these in a computer audio system, see my comments in the next installment.) In the same way that a heavily-modified production car still cannot match a specialist racer up Pikes Peak, a computer based on standard parts will have difficulty matching the sound quality of a CD transport.

Linux, and Streamers Designed for Audio

If Windows or MacOS involves an uphill battle, why not find a better alternative?

Streamers (or network players) can play music from your ripped CD library stored on disk or network drive and from your online sources such as Tidal hi-res, all at high-end sound quality. They connect to your existing DAC, can be controlled from iPad, smartphone or another device, and are not that expensive. How is this possible? Enter the Linux operating system.

Unlike Windows or MacOS, Linux is open sourced (any computer engineer can work with it) and configurable for optimum performance for each application. Your router runs Linux, and so does your smart TV, smart doorbell and your Mercedes. Did I mention SpaceX rockets? Linux’s configurability means high-end manufacturers can offer minimalist software configurations that do away with all those sound-quality-sapping superfluous tasks.

With much less processing work to be done, a genuinely lower-power processor will suffice. In a stroke of good fortune, it turns out that smartphone processors are very suitable for audio streamers. Smartphone processors are low-power (consuming only a few watts), low-noise, and suitable for linear power supplies at reasonable prices.

If a streamer satisfies your needs, it is hard to argue why you would need anything more.

In Part Two of this series, we’ll discuss the Raspberry Pi phenomenon, endpoint streamers, Roon and how to optimize its use, why computer switches and networks can matter, why Wi-Fi can be a sonically superior alternative, and other considerations.

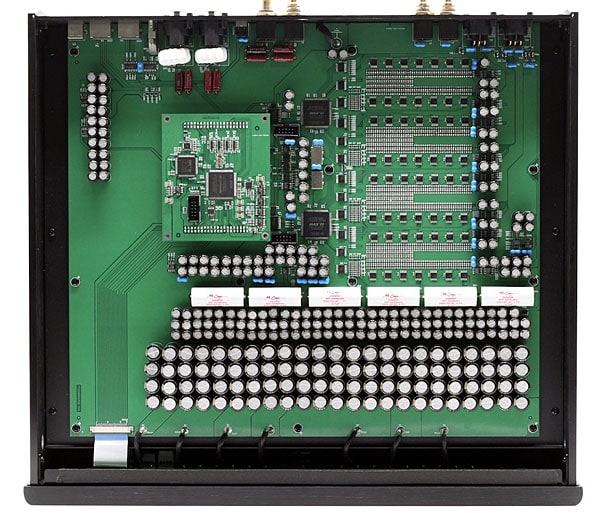

Header image: the inside of a Denafrips Terminator II DAC.

Chord Qutest DAC, US$1,695 from various retailers.

Chord Qutest DAC, US$1,695 from various retailers. Older Apple iPod models. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Chris Harrison.

Older Apple iPod models. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Chris Harrison.

AudioQuest Dragonfly Cobalt USB DAC.

AudioQuest Dragonfly Cobalt USB DAC.

Chord Qutest DAC, US$1,695 from various retailers.

Chord Qutest DAC, US$1,695 from various retailers. Older Apple iPod models. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Chris Harrison.

Older Apple iPod models. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Chris Harrison.

AudioQuest Dragonfly Cobalt USB DAC.

AudioQuest Dragonfly Cobalt USB DAC.