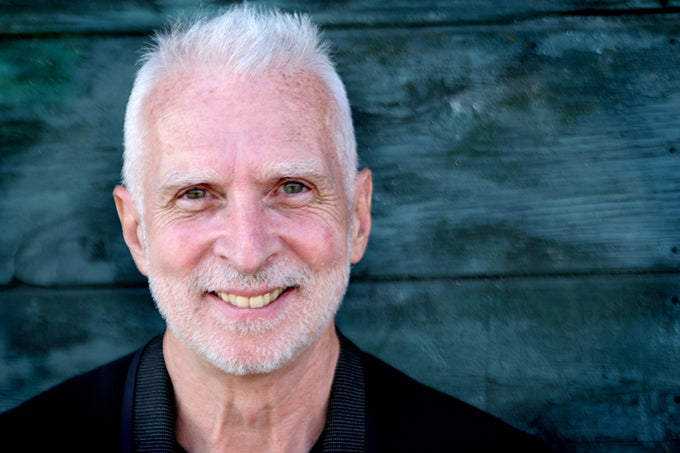

Musician, engineer, producer, professor of 18th Century English literature?!

You may not be familiar with the name Patrick Gleeson, but he has quite a résumé. He ditched a career as a college instructor to become an electronic music pioneer in the late 1960s and 1970s. He created a synthesized version of Gustav Holst’s The Planets that was nominated for a Grammy, composed soundtrack music for television and independent films, ran a recording studio in San Francisco (Different Fur Trading Company), and was a member of Herbie Hancock’s band. Gleeson also recorded synthesizer performances of Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons and the music from Star Wars, along with collaborations with other jazz and electronic music artists.

Part One of this interview appeared in Issue 131 with Part Two in Issue 132.

Rich Isaacs: Who were the other Grammy nominees for the Best Engineered Album, Classical the year you were nominated?

Patrick Gleeson: I don’t know the other nominees who didn’t win, but the winner had figured out a way to extract the piano part of an old recording of a Gershwin piece and surrounded it with a new recording. 1976 sounds right to me. [It was 1976, for Beyond the Sun: An Electronic Portrait of Holst’s The Planets – Ed.]

RI: You mentioned working with (Santana drummer) Michael Shrieve and (Miles Davis saxophonist) Sam Morrison earlier. Have you done any recordings yet?

PG: Oh, yeah, a lot, but the whole situation has been so messed up. We did a live performance that we recorded with a professional engineer in Seattle, a great performance. Since then, I’ve moved the music forward, so we need to have new recordings. We’ve been trying to do that in three different studios, and it’s really almost hopeless because you can’t react in real time to what the other person is doing [because of the latency inherent in recording remotely]. I think at this point, I’m ready to put that on hold until the coronavirus is over. Just by chance, this very morning, KamranV called me – an interesting, interesting man. I just love being around people who are a whole lot smarter than me, and he’s certainly one of them! He started out as, I think, the chief technical officer for maybe Yahoo. He left there early with a whole pile of money in his early 20s, and at that point, he just decided he could do what he wanted. He was the producer of the first Moogfest. Since then, he’s bought this huge, huge building in downtown LA and turned it into a music center with recording studios, rehearsal studios, and all kinds of things that are access points for musicians.

What he’s done with his own time – this guy is seriously smart – he’s developed a means by which you can take a stereo turntable, and with the software and hardware that he has been able to package at a very low price, under $300, you can turn that into a quadraphonic system. I imagine you probably have to put in a different [stylus], but I’m not sure about that.

RI: Yes, when they were doing the SQ and the QS quad formats back in the ’70s, a different stylus was required to play back quadraphonic records because the stylus had to be able reproduce much higher frequencies than what stereo recordings required – around 30 kilohertz.

PG: Well, what he’s done, he now has this package available. You can buy the system itself to make the recordings. You can buy what you need to cut your own vinyl for I think about $2,000.

RI: He’s not talking about converting existing stereo recordings into quadraphonic?

PG: No, he’s talking about cutting quadrophonic recordings. In fact, he has produced a record of Suzanne Ciani’s that’s in quad. The guy is not into the money so the release format is somewhere between a little bit bratty, and poignant. You pay a little under $300, and there are slightly under 300 releases of this album forever, and your album includes the vinyl and the hardware and software you need to turn this into a quadraphonic release into four different speakers. He’s a delightful guy, one of these guys that seems to be very happy about life. We’re going to do a quad album. He had a busy schedule, he was in Europe for a while, but he’s ready to work on our album. So I’m going to put the trio album with Michael and Sam on hold until the virus is over – it’ll be so much better, I would love to record it at Different Fur. I’m going to start the quad album with KamranV. And the piece you heard this morning is one of the pieces.

RI: About the trio with Michael and Sam, do you have any other musicians involved?

PG: You never know, but at this point, we’re thinking just a trio. And when we did it in Seattle, people loved it. It was really great. It was one long set with a 20-minute break, and when we came back for the second half of the evening, they stood up and applauded after every piece. I’d never seen that before. I don’t know if you’ve ever been in a performing band, but if you have, you can kinda tell how well your music went over by how long people hang around afterwards. If they really love it, they just stay on forever. And with this music, I was annoyed at several different venues because the promoter was saying, “we really have to close up now,” [but] we didn’t mind sticking around. People want a piece of you in that experience. Of course, they’ve had it and it’s not reproducible.

RI: How did Devo end up at your studio?

PG: (Independent filmmaker) Bruce Cotter. I used to go down with Bruce and watch [Devo] at the Mabuhay Gardens [in San Francisco]. Bruce became a very close friend of mine and kind of an art guru. I think Bruce understood who I was musically 10 years before I did, and he was a very eccentric man. [Which is] like saying, “King Kong was large.” He would come up and say, “Let’s hear what you’re doing.” And he would just sit there and listen. One time, he said, “I want to ask you a question: Why does the music that you’re playing now and the music you make for my movies, why doesn’t any of your other music sound like that?” Well, he was ten years ahead of me: It all should’ve sounded like that. But at the time, I think I lacked the confidence to just venture off into that kind of weirdness. In a way, he was a guiding light for me.

RI: I recorded those two Devo shows on a reel-to-reel. I can actually lay claim to being the engineer and producer of the first full Devo album, because somebody to whom I gave a copy bootlegged it. It was a direct mono feed from the board – I had asked their permission and they said “yeah.” So in August and September of 1977, I was recording those shows at the Mabuhay.

PG: You put one over on Devo. They kinda put one over on me. I produced two of the songs on one of their albums, but they didn’t give me credit. We didn’t actually ever file suit, but my lawyer sent them a letter of advice, and they finally paid me I think $10,000, but claimed they couldn’t give me credit because the album had already been released. It just wasn’t worth going through suing them.

RI: It was funny the way I found out about the bootleg. I was managing the store Aquarius Records in the middle of ’77 during the whole punk thing, so I got to know some of the KSAN DJs. In fact I ended up helping Norman Davis on his import music show for several months. Sean Donohue called me up one day and said, “Hey, I just wanted to congratulate the producer of the first Devo album.” I went, “What the hell are you talking about?” He said, “Didn’t you hear? Your recording’s been bootlegged.” And I thought, “They’re gonna kill me!” They had my name and address – I had been totally upfront. But I was just naïve about giving people copies of it. People saw me recording at the show and they knew where I worked. They would come in and ask for a copy of it, and I’d say sure. I actually have two different bootleg LP pressings that are sourced from my original recordings. Of course, I have the reel-to-reel masters and those bootlegs were done from cassette dubs, but it was still such a clean feed that it sounds pretty good.

PG: For some reason or other, mono sounds fine for punk. They weren’t exactly punk, but they were punk-ish, punk adjacent.

RI: Who were some of your biggest influences?

PG: The three people in my life who were most influential musically were Herbie Hancock, Gil Evans, and Bruce. I was so lucky to have those three guys take enough of an interest in what I was doing to help me out. They were amazing! Herbie, in two years on the road, probably made five comments or suggestions – maybe five – but he led by example. I learned from him every single night. And the most important lesson I learned from Herbie is: the only thing that matters is how well you listen to everybody else. Especially in improvisation. Gil said the same thing.

The first night I ever played live with Herbie was at the Village Vanguard, and guess who was in the audience? Gil Evans and his best friend, Miles Davis. I literally almost crapped my pants. There was a period of about 20 minutes where I was thinking, “Oh, God, I hope I don’t disgrace myself.” I was so flustered and scared. Then Gil invited me back to his pad in Westbeth (www.westbeth.org), which was this beautiful sort of special housing unit for artists only that New York has. He would sit down and use a little cassette recorder to record the Village Vanguard evenings, and then he’d have me come back the next day and we’d listen to them together. And that was like five master classes in a row.

We would listen together and every once in a while he would just say something. One thing I remember so clearly. I was in real trouble [musically], and Gil heard it. He stopped the recorder and he said, “So what’s going on there?” I said, “I couldn’t think of a thing to play. I didn’t know what to play next.” Gil said to me, “Yeah, that happens to me a lot. But you know what I find? When that happens, I just put my hands in my lap and listen, and pretty soon I find that I’m playing again.” If that isn’t incredibly valuable advice! And bigger than what he said, was what he meant: that listening is more important than chops, more important than anything. Sometimes I hear very young, very talented musicians who are, understandably, just wild about their chops. It’s all about their chops. That’s like stage two [in your musical development], but there are more than two stages.

Dr. Patrick Gleeson and Herbie Hancock.

Dr. Patrick Gleeson and Herbie Hancock.

RI: There were a couple of your albums that I was listening to for the first time over the last few days, and I was really interested in the album Slide. I noticed that you had musicians from Group 87, the Yellowjackets, and (Kronos Quartet cellist) Joan Jeanrenaud on there – was she your wife at the time?

PG: Yes.

RI: Was there anyone else? It seems like there was some percussion.

PG: The percussion was me. There was just Marc Russo and Joan and Peter Maunu.

RI: Related to that, on the Bennie Maupin album, Driving While Black, there was quite a mix of electronic percussion and acoustic drums, and I was wondering if you were involved in the programming of the electronic stuff.

PG: Yes, it was just Bennie and me. The way that album was put together…I had already produced one or two albums for him, and then we’d been in the band together and had played on other records by other people. So I really understood Bennie. I deeply understand where he’s coming from musically, to the extent that I’m able to understand anything – I’m limited, of course. I’m deeply sympathetic to what he’s doing. So what I did with that album was, we talked about where we were going to go. I sent him some very, very early versions of every tune – one of which he rejected. He said it was just way too close to something from a Miles album. He was undoubtedly right: I’ve been stealing from Miles all my life.

Then I just completed the whole album – quote “completed” unquote the whole album – and Benny came over to my house and studio. I said, “Do you want to listen to what we’re going to be recording?” and he said, “Nah, let’s just start it.” So what you hear is a combination of the first take, second take, and the third take – but mostly, I would say, 60 to 70 percent the first take, maybe five percent I took from the third take. And this is the first time he’s heard the music, he doesn’t know where it’s going – he’s improvising. We did it in, I think, two afternoons. And after he left, I went back and pared down what I was doing and redid some stuff to match what he was doing. I’ve always found that a very friendly way of coming to a recording. If you’re going to have to do a synthesized orchestration for the guys to know where you’re going, then be very, very willing to change that orchestration drastically to match what they’re doing. If you do it right, it sounds like it was all recorded together. Slide was done that way.

RI: Was it just the two of you?

PG: Yes.

RI: So you did the drums and the electronic drums?

PG: Yes, but they’re all electric.

RI: But it sounded in places like some of it was acoustic.

PG: They were originally acoustic samples.

RI: But it’s all done through programming?

PG: Yeah.

RI: Arthur Brown (of The Crazy World of Arthur Brown) was one of the very first recording artists to use a drum machine with his band Kingdom Come (not the “hair metal” band of the 80s) – it was the Ace Tone Rhythm Ace drum machine, and it was a precursor to the Roland and Linn drum machines. Arthur tells a story about one gig at the Marquee Club where damp conditions caused it to misfire, and they had to follow it for 75 minutes. So do you have some weird stories like that to tell?

PG: I did a concert with a West Coast orchestra. I had two double-manual Prophet 10 synthesizers. And one of them, after a certain number of minutes, overheated and in the middle of this live orchestral performance, the second Prophet 10 began doing random sequencing. The conductor and orchestra stopped, and I just turned that machine off, and we started the piece over again.

RI: Who are some of the people you have most enjoyed working with?

PG: Well, Herbie, of course. Highest on the list, I suppose. Probably Lenny White’s high up on that list. Bennie Maupin. All the people I played with on Slide are certainly people I enjoyed working with. Those are the ones that first come to mind.

RI: You wrote in your bio that you told yourself you’d stop scoring films when it stopped scaring you. What was it about doing soundtracks that was frightening?

PG: Number one, I’d never done a soundtrack in my life, and suddenly I’m now hired to do a network series. I’d never scored to image in my life, except avant-garde stuff with Bruce. So I’m not competent. I may be talented, I may have a potential, but it’s not yet been realized, and I’ve got four days to realize it.

RI: What was that TV series?

PG: I can’t think of the name of it now. It was a story line of four little girls living with this man who’s their guardian, in this big house. One is Black – I can’t remember her name but she went on to be a pretty well-known actress – and one I think was maybe Latin or Asian. It was a comedy and supposed to be about the 1950s. I got my first introduction to what TV scoring was going to be about when they called me in after the third episode. J. Peter Robinson was doing the series before that, and he started getting feature offers. So Peter called the producer, Len Hill, and said, “I’ll do the next couple of shows for you, but then I want to move on.” And Len, being the a-hole he was, said, “I’m going to be very disappointed in you unless you can find me someone of similar caliber.”

Peter gave three of us (potential scorers) examples of what he was doing with the show and had us submit tapes, asking us basically to do something that was a rip-off. And I got the gig. The producer said, “now, Pat, what you’re doing is very nice, but it’s not exactly what we need. We need an underscore – what you’re doing is more like an overscore.” He also said: “just so we get off on a premise we both agree on: you’re coming in hard on all these cues. Start every cue with like a two- or three-second drift into the cue.” Then another thing happened that got us off to a rather strange start – when we talked about [what the score needed], he said, “it’s ‘50s rock-n-roll high school.” I said, “oh, perfect! Chuck Berry!” He said, “yeah, Chuck Berry – that’d be great!” Well, every time he hears a Chuck Berry tune [in the score], the guy craps! Way too energetic. Took up way too much audio space. So it turned out just to be another dreary TV sitcom. But it paid $10,000 a week to start. At one point, I was making $25,000 a week.

PG: I can see why, in your bio, you called it “stupid money.”

RI: And there were repercussions to that that went on and on. What happened was, the colleges – may they roast in hell – looked at what was happening in the TV industry and realized here was a great new opportunity to enroll students in film-scoring programs. First there was just Columbia, UCLA and USC – and they had all very good instructors and very good programs. But within two or three years after [the colleges] realized what the f*ck was going on, and particularly when you could do all this with synthesizers, [you’d see] film programs at Podunk U by a guy who had once scored a local McDonald’s commercial. It was just incredible.

And then, the next thing that happened in my life – this is the mid-‘80s – I was getting calls from young guys, it was all guys at that time, [and the conversations would go something like this]:

“Mr. Gleeson, I want to get some advice from you. I’ve graduated from (wherever) and I’ve been out of school for over a year and I’ve never gotten a gig.”

“Yes, it’s tough to get started.”

“Now I do have an opportunity, but I don’t know whether or not to take it.”

“I’m sure, whatever it is, you should take it.”

“They’re willing to have me score (something for television), but they don’t want to pay anything for it.”

I construed that as meaning very low pay, and I responded with that understanding until [the guy would get] very upset with me.

“No, you don’t understand. They don’t want to pay me anything. They say it will be good for my bio.”

“That’s just terrible, but at least you’ll get the writer’s share of publishing.”

“They’re taking that, too.”

So that’s what happened because guys like me, and J. Peter Robinson, and Cory Lerios from Pablo Cruise – we all got onto the Synclavier [an early digital synthesizer – Ed.] early. Of course, you had to have money, because the Synclavier was so expensive – which was very nice for all of us because it limited the number of people [who had access to the instrument]. Then it almost became de rigueur for a few years that to score a network series, you had to do it with the Synclavier, if you weren’t doing it with a live orchestra.

It was such a good thing that we ruined it for ourselves. When I started, there were maybe 250 people worldwide doing what we were doing. Supply and demand then created a glut of composers. I now know a guy who’s won a couple Emmys, and he’s working for about $4,000 a week, which is just stupid. There are expenses that come with that – you’re buying new equipment and new software. So $4,000 a week doesn’t leave a lot of profit.

RI: Because Copper magazine is produced with audio and music enthusiasts in mind, we’re always interested in hearing about what sound systems musicians have, although it seems like an awful lot of musicians do not seem to care about really high-end reproduction at home. I’m wondering where you stand on that.

PG: In my studio, I have the medium-sized PMC monitor speakers, which are now ridiculously expensive. I think the ones I have now sell for $11,000 a pair. I didn’t pay that much for them. When I got mine 17 years ago, I think they were $5,600 a pair. I have Bryston amps [and] now that I’m going quad, I just acquired a couple of nice medium-sized Hafler [amps]. Downstairs – you would just scoff – we have a little disc player/music system, and you can plug your iPhone into the back of it. It’s a little box about 14 inches wide and 10 inches deep with built-in speakers.

My wife Charmaine listens to music in the house more than I do. I find it difficult to do anything else when I’m listening to music, and vice versa. I think that started to happen when I was with Herbie. When I first joined [his band], I was humiliated to discover about myself that I would space out, having little fantasies of this and that while on the bandstand. When you do that with a band like Herbie’s, you’re lost. So, quickly, I disciplined myself.

Then I discovered that the reverse was [also] true. Billy Hart was the drummer in Herbie’s band, an amazing guy with a strange, wonderful sense of humor. Once Billy and I were staying on the tenth floor of a hotel together. We got into the elevator and Billy started talking to me. At the ground floor he said, “You haven’t heard a word I said.” They were playing Muzak in the elevator and one of the violins was out of tune, and that’s all I heard for 10 floors all the way down.