When the legendary Al Schmitt passed away on April 26, 2021 at age 91, he left behind a tremendous musical legacy. He was one of the last of the great, surviving music recording engineers to have worked during the post-World War II era through to the present. In addition to 20 Grammy wins, Schmitt amassed credits for over 150 RIAA-certified Gold and Platinum albums. Like his mentor Tom Dowd, Schmitt was musically omnivorous and worked in almost every genre of popular music, with artists including Duke Ellington, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Frank Sinatra, Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, Jefferson Airplane, Toto, Steely Dan, Jackson Browne, Diana Krall, Shelby Lynne, Henry Mancini, Luis Miguel, Trisha Yearwood, and The Mavericks, just to name a few.

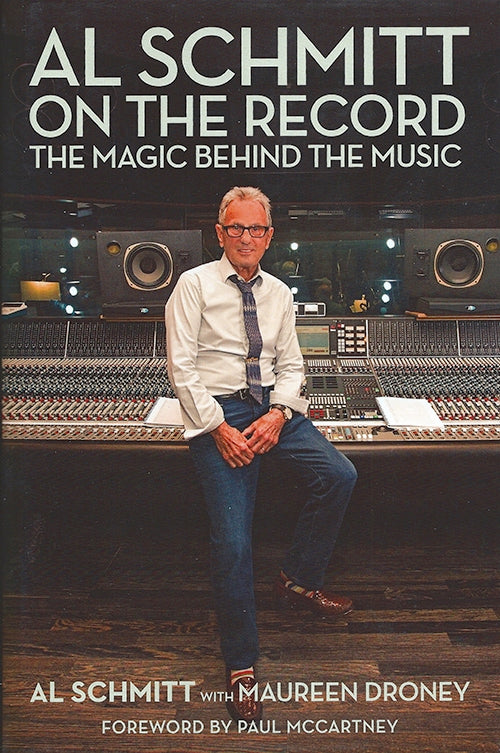

As he entered semi-retirement in 2018 (although he continued to work on records in 2019), Schmitt published his autobiography, Al Schmitt On the Record: The Magic Behind the Music. I was fortunate to briefly meet Mr. Schmitt in 2019, following a presentation he gave for Mixing With The Masters at the Audio Engineering Society (AES) conference in New York. Although authorship of the book is credited to Schmitt with Maureen Droney (senior managing director of the Recording Academy Producers & Engineers Wing), the stories and explanations that comprise the bulk of the memoirs are unmistakably in Schmitt’s gruff voice, and his hardscrabble Brooklyn roots and attitude permeate through every page.

Inspired by his uncle, who was an audio engineer prior to World War II, Schmitt and his younger brother Richy would follow the same path after Schmitt finished his service in the US Navy. As a fresh-faced assistant to Tom Dowd, Al Schmitt recalled his baptism of fire: being mistakenly scheduled as the recording engineer for a session with the Mercer Ellington band, with Duke Ellington in attendance. Schmitt had no experience as a main recording engineer and, knowing who Duke Ellington was, went into a panic. However, Duke reassured and encouraged him. Emerging from the experience successful and confident, Schmitt would snowball the serendipitous Ellington session accident into a career that covered a wide cross section of the last 70 years of popular music.

Al Schmitt. Courtesy of Chris Schmitt.

Two of the most remarkable aspects of Al Schmitt’s approach to producing and mixing were his sublimation of ego, and his open-mindedness towards new technology, the latter particularly striking when compared to the number of his peers and younger colleagues who long wistfully for the older sounds of analog equipment and gear.

Schmitt’s ability to put his ego out of the way was a huge part of why he was constantly active long into his 80s. His willingness to work in any music genre and to deliver the best sound possible for the artist, without injecting his own trademarks, (like Phil Spector, for example), resonated across the industry, making him the first-choice request of producers like Tommy LiPuma and Phil Ramone (a top-notch engineer in his own right), and such a diverse range of artists.

The incongruous relationship between hippie counterculture forerunners Jefferson Airplane and Schmitt, the ex-Navy Brooklynite who always came to the studio in a suit and tie, was especially fascinating. Schmitt recalled that the sessions were nothing like he had ever previously experienced, with long hours throughout the night as the Airplane composed much of After Bathing at Baxter’s (1967) in the studio, with the number of takes of a song running into the mid-hundreds at times. Unhappy with producer Rick Jerrard, who had put the band on the map with the previous album Surrealistic Pillow (1967) and its iconic singles “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit,” the Airplane told RCA Records that they specifically wanted Schmitt, whom they liked personally after meeting him, to produce their next LP. (Schmitt was working for RCA at the time.) They were apparently unaware of his past work with Sam Cooke and others, but his patience, experience, and musical sensibilities proved invaluable, with Grace Slick especially singling out Schmitt as the one who “saved all their asses” in the studio during the recording of Baxter’s.

For his part, Schmitt, who likened his job of producing the Airplane to being “the dogcatcher with the butterfly net,” was able to look past the chaotic goings-on and appreciate the musical virtuosity of bassist Jack Casady (in spite of his volume, which required his speaker cabinets to be recorded from a separate room!) and lead guitarist Jorma Kaukonen, as well as the studio discipline of vocalist Slick, who was practical, a perfectionist, and as Schmitt recalled: “…she was smart, a Vassar girl, you know.”

Schmitt went on to continue as Jefferson Airplane’s producer for Crown of Creation (1968), Bless Its Pointed Little Head (1969), and Volunteers (1969), the last one as an independent producer apart from RCA. He also would produce the first three albums for Kaukonen and Casady’s spinoff band Hot Tuna, as well as Paul Kantner’s Jefferson Starship debut, Blows Against the Empire (1970). The personal relationship continued until Schmitt’s death, with Schmitt recounting in the book that he still spoke regularly with Kaukonen and Casady, whom he described as having since transformed from drugged-out hippies to the “salt of the earth.”

Schmitt recalled the making of his collaboration with producer LiPuma on George Benson’s groundbreaking Breezin’, the first record to feature the hotshot jazz guitarist as a vocalist. Excited about the prospect of showcasing his singing talents, Benson nailed a number of the songs, including the hit “This Masquerade,” on the first takes. Schmitt’s use of a cheap Electro-Voice 666 mic, originally intended solely for a guide vocal scratch track, wound up becoming Benson’s lucky charm, and he superstitiously stuck by it for his subsequent records. Schmitt also recalled the problems of recording the strings in a Munich, Germany studio, as the multi-track tapes were recorded at 30 ips and the main studios there only recorded at 7-1/2 and 15 ips. They finally located the only studio in Munich with a 24-track recorder operating at 30 ips, but the room was so small that the violinists’ bows were hitting the ceiling when they played. Needless to say, the lack of air and the quality of the sound in the room made for string tracks that fell considerably below Schmitt’s professional standards.

Ironically, Schmitt won an engineering Grammy in 1976 for Breezin’. Upon hearing that he was nominated, Schmitt laughed, and his response was: “Really? Has anybody listened to the strings?”

In the book, Benson comments that Schmitt’s recording of his guitar was “the best he had ever heard” when they first worked together on Breezin’. In another story indicative of Schmitt’s innate instincts for when a performance was stellar, and the benefits of his fastidious work habits, Benson cited his hit rendition of “On Broadway” from Weekend in L.A. Recorded with the Wally Heider mobile unit, Benson felt that his second show’s performance of “On Broadway” was “magnificent,” and Schmitt made him a cassette copy. After the shows were completed, Benson and producer Tommy LiPuma met to review the tapes to mixdown to 2-track, but could not locate the second performance of “On Broadway.” The multitrack reel was nowhere to be found, and LiPuma was concerned that it had been erased and recorded over, as the concerts had run longer than anticipated, and LiPuma had re-recorded over the first show’s reels to continue recording, since Benson was less than satisfied with the first show’s performance.

However, Schmitt had also realized that the second show’s “On Broadway” was exceptional, and had safely stored the multitrack master tape away. Benson considers “On Broadway” one of the most important songs he has ever recorded and credits Schmitt with saving his career as a result.

One of Al Schmitt’s more unique workarounds is the now-famous tape loop he created for Jeff Porcaro’s drum track from Toto’s signature song “Africa.” In pre-digital-age 1982, the only way to create a repeating musical loop was by splicing a length of tape into an actual loop. Although Toto was comprised of some of the finest studio musicians in Los Angeles and Porcaro was one of the top A-list drummers in the industry, he and percussionist Lenny Castro were unable to play the part envisioned for “Africa” with the metronomic precision Porcaro wanted for the entire track. Choosing the best two bars, Schmitt had to create a tape loop that would be long enough for the repeating two-bar section. As a result, the tape loop “had to go from the left reel of the tape machine, around the mic stand [a few feet away], and then back to the right reel of the tape machine.”

Schmitt was open-minded enough to embrace technology, but without becoming dependent on it, in pursuit of maintaining his professional standards. As someone who had learned audio engineering in the early direct-to-acetate mono recording era, a key component of Schmitt’s ability to capture such great sounds and performances was via his skillful use of microphones. Unlike other engineers, Schmitt’s school of thought focused on capturing the desired sound at the source – the mic – which would subsequently introduce less noise and/or artificiality into the sound by requiring less equalization and other processing during the mixing stage, and result in a more pristine final product. Schmitt’s encyclopedic knowledge of microphones, their applications, and their tonal qualities determined his infallible microphone selections for every vocalist, instrument, producer’s demands, or task at hand. Schmitt would choose each mic for its unique qualities and ability to match the kind of room it would be used in and where it should be placed, and the playing or singing style of the artist. All of these decisions were things Schmitt would determine based on a combination of instinct, experience, and mental calculations of acoustic physics.

While he had vintage Neumann, Sennheiser, RCA and other microphones in his huge personal collection, Schmitt’s focus on quality led him to eschew preconceived biases and objectively add microphones from Audio-Technica and other newer manufacturers to his rotation whenever they would better deliver the sounds he was pursuing. Schmitt’s longtime recording venue of choice was Capitol Studios, and Schmitt worked there so frequently that he had an office on the premises and jokingly referred to manager Paula Salvatore as his “other wife.”

Al Schmitt’s use of Capitol’s legendary echo chambers and the studio’s famous mic collection also became a mainstay of his M.O. As Schmitt’s longtime assistant Steve Genewick details in Appendix A of the book, Schmitt would routinely blend Capitol’s chamber Four – his favorite – with a Lexicon 480 digital reverb processor, his personal Bricasti reverb, and Capitol’s EMT 250 plate reverb in order to quickly create a sense of space and depth that he felt would best enhance a mix.

Al Schmitt On the Record: The Magic Behind the Music not only contains the author’s philosophies and perspectives on music and the industry, but freely includes very specific details about Schmitt’s methodologies, equipment choices, and microphone placement secrets.

Reminiscences from Shelby Lynne (whose Dusty Springfield tribute, Just a Little Lovin’ has been praised for its pristine sound) on working with Schmitt and producer Phil Ramone were effusive, and somewhat ironic, as she chose Schmitt specifically for his engineering expertise because she wanted to record to analog multitrack, and Schmitt was initially reluctant, as he had been working so often in digital!

In addition to his meticulous use of microphones, Schmitt developed a habit of recording with the final mix already in mind, unlike other engineers who focused more on capturing individual sounds with mixing decisions left for later. Engineers Steve Genewick, Niko Bolas and Bill Smith all learned from Schmitt and believe that Schmitt’s unique approach was borne from his long experience in recording from the mono days all the way through multitrack tape and then to digital. Schmitt’s knowledge of what the actual instruments should sound like when played together played a huge part in his expertise, and he would choose new tools that enhanced his main objectives of making records, but without becoming dependent on them, and losing his fundamental principles, which stemmed from the ability to make records using bare bones equipment.

Al Schmitt On the Record: The Magic Behind the Music is a fitting legacy for a titan of the music recording industry. It contains a wealth of information not only for audio engineering enthusiasts, but for music historians and readers who are curious about the making of iconic records, some of which are likely to be part of their music libraries.