If you have listened to any popular music from the last 75 years or so that was remastered for CD, DSD, SACD or limited-edition vinyl, there are very good odds that you have heard the work of mastering engineer and audio restoration expert Steve Hoffman.

Steve has remastered and restored thousands of classic records from artists as diverse as Ray Charles, Frank Sinatra, The Eagles, Chicago, Sonny Rollins, Muddy Waters, Buddy Holly, Bob Marley, The Beach Boys, Bob Dylan, Rage Against the Machine, Steely Dan, Johnny Cash, Nat King Cole, Earth, Wind and Fire and countless others…the list is staggering in both volume and breadth of musical genres.

Steve Hoffman’s philosophy on remastering is predicated upon a quest to capture what he refers to as the “breath of life”, i.e., to make the artist sound as true to life as possible. Steve’s touch has wowed millions of listeners and has garnered a huge fan base – an anomaly when one considers that the average music listener has no idea what an audio mastering engineer even does. Yet Steve is well-known enough to host an extremely popular forum, (www.stevehoffman.tv), with about 127,000 subscribers.

Such is the magical connection of music. Steve Hoffman’s decisions in the studio have preserved and improved much of the beloved recorded music we own today in our personal libraries, and I think I can speak for every music lover to say that we are all grateful to him for his work.

Copper last spoke with Steve a few years ago (Issues 36 and 37). He discussed some of his past work, his love of vintage tube equipment, his preference for analog tape editing, some of his theories on remastering, and some of the obstacles he had to overcome on the technical, psychological and political fronts.

During this period of COVID-19 lockdown, Copper was fortunate that Steve had some downtime between projects, which allowed him to do this follow-up interview.

John Seetoo: You have lamented that a lot of the recorded sound of contemporary bands is the result of over-compressing the dynamic range, what’s become known as the “loudness wars,” and that the sound is sometimes unduly harsh-sounding due to digital signal processing and a focus on mixing for streaming and headphone listening. As a result, your preference leans much more towards audio restorations of music recorded on classic analog tube equipment. Would you consider new mastering projects but from artists and producers who appreciate and continue to use old-school tube gear and analog tape, such as the Foo Fighters or Tony Visconti?

Steve Hoffman: Of course, but no one wants this type of “old school” mastering any more. It’s not “loud enough.”

JS: As the source material in such a project would be fresh, instead of choosing from multiple versions as you would do with your re-mastering projects of classic material, would your approach in working with the producers and artists differ, if they wanted to make changes after the fact, vs. your standard “do no harm approach?” For example, you dissuaded Ray Charles from wanting to redo his vocal on “Hit the Road Jack.”

SH: I would encourage producers not to squash the dynamics in the original mix, but rather leave that option for mastering so that there would be some dynamic range to work with in going back to the original master tapes. Some producers don’t understand that at all.

JS: The Steve Hoffman “breath of life” philosophy of focusing on making sure that a singer sounds like the actual person or a soloist’s instrument sounds like the real thing and letting the rest of the pieces fall into place is likely a huge part of why you have such a devoted fan base.

Without divulging any trade secrets, how do you approach separation and maintaining realism in duets with vocalists with similar voices, such as when you re-mastered The Righteous Brothers – if you are working off of a mono mix?

SH: Mono, stereo, doesn’t matter, a human person sounds like a human person. You know it when you hear it, right? Well, so do we all. I just make sure that this is something that will work for everything. In mastering I strive to make human voices sound real. It doesn’t matter how many are singing at one time. Unless they are on two different microphones, and then it’s more of a struggle to get them to sound human.

JS: How would you approach that same question regarding the sound of instruments? For example, with a group like The Allman Brothers Band, where Duane Allman and Dickey Betts had similar Gibson Les Paul guitars and Marshall amps?

SH: Nice question. First time I’ve ever been asked this one! I would concentrate on the drums first if I could. Make sure there was something there that sounded “real.” How much of that goosing of course depends on what it’s doing to the rest of the instruments. Strike a fair balance between everything, that’s the ticket. Hard to know when to stop, but it takes practice.

I’ve done just about everything to goose something into sounding better: EQ changes, slight tube compression, adding layers of tube [electronics] in playback to add body to dead-sounding stuff, using different tape machines, feeding the signal back into a big room and adding a bit of the “room” to make it sound more pleasurable, etc. Whatever it takes.

JS: While a mono mix can often be the best source material for a restoration job, have you ever been required to create a stereo master from a mono mix for the sake of a client’s marketing agenda? If so, did you keep it analog or have you deployed digital to achieve acceptable results?

SH:I never have, not once since 1982.

JS: You’ve cited the Beatles’ “She Loves You” as an example of a song with multiple tape edits that used echo to hide the splices. In your re-mastering work, have you ever had to add echo or some other processing to conceal a physical analog edit that wasn’t on the original master?

SH: A few times, usually at the end of a song when it’s cut too close. Listen to Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say” on the two-disk Ray set I did. The last note cuts (chopped off by engineer Tom Dowd). I added reverb to match at the end only, sounds better. Normally I just leave obvious splices, console pops, etc. I like to hear that stuff, it makes me appreciate how much a song is worked on by all concerned. No one else agrees with me on this though!

JS: You have mentioned your close working relationships with people like Ray Charles, Sammy Davis Jr., Ian Anderson and others whose records you have restored. How do you approach re-mastering records where the artists and/or producers have passed away or are unavailable for input feedback? Do you choose a personal favorite recording from that artist’s catalog as a reference?

SH: I never ask artists for feedback. That way lies disaster, trust me. If they like what I do, great, but I never ask for their blessing. Would be pointless.

JS: As a tube gear aficionado, have you been following the explosion of new, boutique manufacturer-designed headphone tube amps? Have you heard anything that could change what has been your negative opinion towards headphones?

SH: I don’t hate headphones; I just wore them for years [when I was] in radio broadcasting and I’m done. Back when I was living at home, I needed good cans so as to not wake my parents. Now, it doesn’t matter, I’m sleeping too! I have a nice Woo Audio (made in New York City) headphone amp and a few pairs of headphones. I enjoy them once in a while, but not for any critical listening. The mix balance on cans throws me way off.

JS: You had a revelatory experience with the small McIntosh tube amps back in the 1990s, but now your website lists Audio Note as your exclusive brand for preamp and power amp use. What is it about Audio Note gear that appeals to you, and what features, if any, are missing that could cause you to switch if you found them in another brand?

SH: I got involved by accident with Audio Note UK. My friend was looking for a turntable and the Audio Note rep brought one over for him to try. We started chatting and I told him I always wanted to hear an Ongaku, ever since the days I saw the circuit in [the now discontinued] Sound Practices magazine. He said he had one and brought it over. That was the start of it. I love single-ended triode [amplifiers], and finding speakers that can move me musically on 10 watts was always the goal. The Audio Note AN-E speakers do that nicely.

That being said, I use the PS Audio PerfectWave transport and DirectStream DAC as my main digital playback system. Works quite well with the Audio Note UK gear.

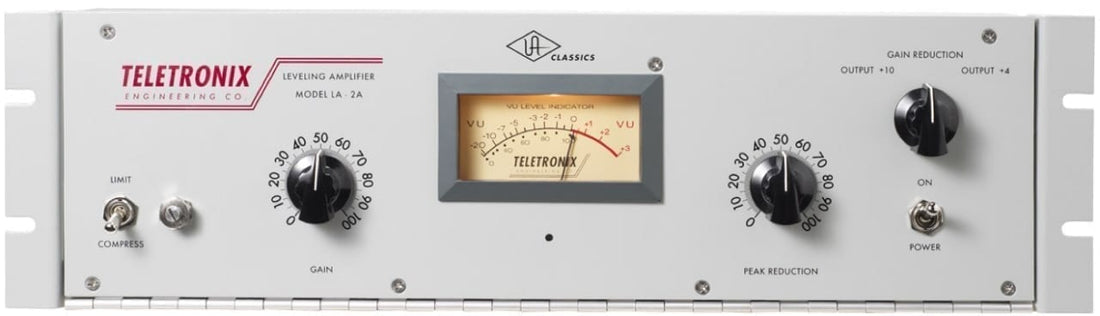

JS: You are known for trying to keep the signal chain as minimal as possible and will sometimes bypass a console or swap tubes to get a different sound instead of deploying any outboard processing. In your mastering work. Are you using vintage gear like Pultec equalizers and Teletronix LA-2A compressors, or any comparable newer gear when needed? What kind of processing equipment are you currently using?

SH: I use and trust the GML 9500 Mastering EQ unit, my vintage Universal Audio EQ’s and the Teletronix LA-2A when needed (which is seldom). I’ve also used the Sontec MES-432C parametric equalizer. Anything else is just for a needed “trick” or so during mixing, which I do a bit of when I get something old that needs a remix.

JS: Do you use your personal analog Ampex and Otari analog tape machines exclusively, or would you rent a Studer or other unit for playback as needed?

SH: I use my home stuff rarely, mainly to fix splices. When I’m ready to actually master I’ll use a studio that has what I want. Marsh Mastering in Hollywood has the Studer and Ampex machines I like.

JS: For monitoring you use Audio Note and Rogers LS3/5a speakers combined with a Tannoy 15-inch subwoofer. What do you like about this combination, and what steps led to your arriving at it? (According to the website as of Feb. 2020.)

SH: No, I don’t use that combo. The Audio Note stuff is all AN speakers. Another system has vintage McIntosh [and] Marantz [electronics] and my 1968 Tannoy Lancaster speakers. The Rogers LS3/5as I have are used when I need a “dinky” perspective.

JS: You have several different turntable (VPI, Technics) and cartridge (Grado, Shure) systems. Do you often find that vinyl or old acetates are a better audio source for a restoration project rather than tape, or do you only use them when they are the sole existing source?

SH: I haven’t used acetates in years but it is seldom all there is (from the recording tape era). There is always a country that has a dub tape of something. Pre-1949 I’ve used transcription lacquers, etc. for sources but [I haven’t had to do that] for a long time. I use my turntables for listening fun.

JS: If you were re-mastering a recording of an unfamiliar world music genre, like Indonesian gamelan music or Tuvan throat singing, would you approach the project on the fly with your subjective first gut instincts or would you research some other recordings first to get a range perspective on how the instruments and singers can sound?

SH: I would do the research first, yes. Crucial not to go in blind. On the other hand, sometimes ignorance is true bliss because the music is usually transferred with a light hand and that’s always better than some compressed lute with too much air and extra echo to make it sound like you’re listening in the cheap seats…

JS: Have you ever had to compile a single master from several disparate versions with drastically different EQ requirements, due to age and damage rendering each version unusable on its own? In such a case, would you rely on an intact earlier digital transfer, or would you maintain it in the analog realm like the way you re-mastered Jethro Tull’s Aqualung?

SH: It would depend. I’ve had to use many, many “pieced” songs in my years of doing this. Even I can’t remember where the changes are, so I must have done a good job. I would do it digitally if it was really tricky but in the 90’s only analog would do. Now, if it’s going on a 16-bit CD, I’d do it digitally. [If it was being remastered for] SACD, in DSD, and so on. However, if it’s an LP [re-master[, it will remain analog and I’d rather have a slightly damaged section than dump to digital. I mean, what’s the point of that to make an analog record?

JS: Popular music often has a drum beat or other areas where a tape edit can seem relatively seamless. How do you approach edits in classical or jazz music, where the edit points may stand out more glaringly? Would you use echo or other processing when doing a restoration in that instance, or do some kind of cross fade to hide the edit point?

SH.: Well, the trick is to echo the beginning of the edit piece as well. Usually edits can be heard because the original engineer spliced a section without echo but without the echo from the earlier section coming through. Common mistake. I’ll do a backward (tape reversed) echo splotch to get some reverb at the beginning of the splice to match the passage before. Then no one can tell. But editing classical is hard (but not impossible, as 70 years of finely-edited LPs have shown us.) And believe me, there are more edits in our beloved RCA-Victor Living Stereos and Decca/Londons than you could possibly imagine. I once counted over 40 splices in one short Living Stereo passage and I swear I couldn’t hear one of them. Only (by) watching the tape is there a clue. That’s a true pro job!

JS: Have you ever been approached to restore the audio for a film? If so, what challenges and protocol changes did you have to overcome? If not, is there any film in particular that you think could benefit from a Steve Hoffman audio restoration?

SH: Film audio? No, but film music, yes. I worked (moonlighted, actually) at Warner Bros. and helped with score restorations on some of their classic flicks (The Music Man, Gypsy, etc.) Grim work with decomposing stock. Bad for the lungs. Had to quit after a while, couldn’t take the smell any more.

But you’re asking if certain films could use a sonic remix? Sure, but that’s not my area. Would be fun to try though…

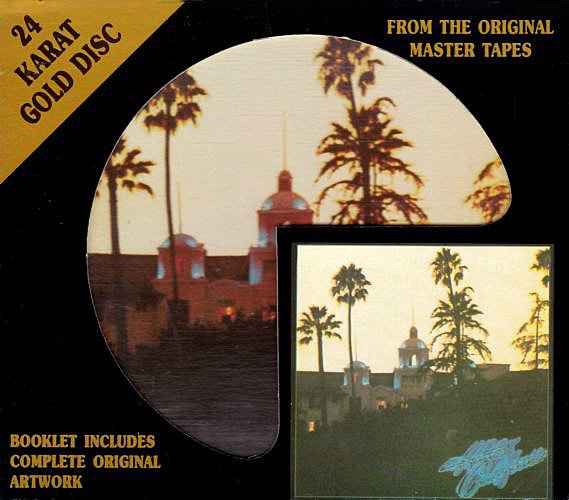

JS: In another interview, you cited The Eagles’ Hotel California as a particularly challenging project, due to excessive boominess on the original mix. Do you find that these kinds of issues increased due to the exponential rise of variable-location multi-track recording, and that completed projects in a single studio with a limited track count often led to a better-sounding finished mix? Or do you think it has more to do with the engineer and choice of room for the session in question? Please cite examples, pro or con.

SH: It all comes down to the final mix stage. Sometimes the monitors used cannot show what is actually happening – a good thing in some cases, not so good in others. If there are changes in sound from track to track, I usually leave them for the most part. I think it’s charming. But wild changes of course are disturbing to most and those have to be “fixed” in mastering. Engineers that mix on dinky speakers usually only ever listen on similar speakers. I never mix or master on dinky speakers; they can really throw you off. I could write a book on this subject but I’ll stop here.

JS: The late Dennis Ferrante (John Lennon, Lou Reed, Wynton Marsalis) told me that when he did the remixes for the Elvis Presley CD box set Walk A Mile in My Shoes, he had to go back to the original multi-track tapes because the 4-track mix-downs from RCA were done haphazardly – the stereo balance had a -5dB volume discrepancy, and percussionist Ralph MacDonald’s parts were erroneously muted in the mix-downs.

Would you ever take a project that might require restoring or re-recording an instrument or other parts to a mix before re-mastering, or do you only work with finished mixes?

SH: I guess I could but why would multi-tracks be mixed down to 4? You mean for Quad [quadraphonic sound] or something?? I only know of Columbia [Records] and their weird habit of mixing down 8 channels to 3 and then from that to stereo or mono. The Byrds [recordings] are like that. It’s a pain in the butt because goofs and bad mixing choices are there for all time. Yet, going back to the multi and starting over is also bad; you lose all the charm of the original versions and everything sounds “modern.” I hate those remixes, never listen to them (talking about YOU, Pet Sounds!) I’ve flown in instruments before. Sheet, I’ve even added a snare drum to a damaged section of a song that lost the snare. Used my own. Was fun, and a little naughty.

JS: As a guitarist who appreciates vintage instruments, what is Steve Hoffman’s favorite guitar sound and what records have you mastered that have achieved your “breath of life” standard of that sound, when the original-release guitar sound may have been less than optimal due to a label rush job, pressing from a backup master, etc.?

SH: Wow, these questions are amazing. Really giving me a workout. My favorite guitar sound? Hmmm, Stratocaster into a tweed Fender Bassman (Buddy Holly, The Fireballs’ sound*), Gibson humbucker with treble rolled off (“Dark Eyed Woman” by Spirit), a bunch. I like songs where the guitar is so unprocessed that I can tell what the heck it is, James Burton’s Tele in Ricky Nelson’s stuff, Steve Cropper’s Tele and Bassman duo on the Stax/Volt stuff, etc. Too much processing and it doesn’t matter what guitar is even used.

Albums that I have brought out a better guitar sound than the originals? Hmm, hard to say. Buddy Holly, some Beach Boys; in jazz, Barney Kessel in The Poll Winners stuff, Kenny Burrell, Grant Green.

(*note: The Fireballs were a band contracted by Producer Norman Petty during the 1960s to add backing track overdubs to Buddy Holly’s unreleased demos posthumously.)

JS: Are you excited about any current or upcoming projects that you are at liberty to share with Copper readers?

SH: Can’t share, everything is on hold, no one has a clue as to what will be released. It’s sad but that’s life.

JS: What would be the top 10 achievements of your career that you would like to be best remembered for after you decide to retire? The list can include recordings, techniques, or philosophies.

SH: I can’t. It’s too Sophie’s Choice for me…I like to think I’ve spread the word to let recordings sound as natural as possible, even Death Metal, etc. And the importance of [using] a good original source when doing reissues.