I installed a new cartridge on my record player about a month ago. I bought my previous cartridge about six years ago during a visit to Japan, when the yen/dollar exchange rate just happened to have hit bottom. It was my first Ikeda cartridge. Isamu Ikeda is a grand master phono cartridge builder, and some consider him the father of moving coil cartridges in Japan, having founded Fidelity Research in 1964. The Fidelity Research FR64 tonearm, and the FR1 and FR7 cartridges were iconic products, but these were rare birds outside Japan in that era.

Ikeda Sound Labs was established in 2011 and continues to manufacture tonearms and cartridges. The original FR1 and FR7 were cantilever-less designs, similar to the Decca cartridges. This design excels at lifelike dynamics, but the cartridges are very difficult to align and can only be used with well-damped tonearms. The modern Ikeda cartridges all employ a cantilever, and can be matched with many different tonearm models. The orange-colored 9TT is in the middle of the range, with the blue-colored 9TP (called Kai in the export market) at the top, and the green-colored 9TS at the entry level. You should be aware of several issues with these cartridges. They are very heavy, and have a very low output of 0.17mV. (The FET/tube cascode input of my phono preamplifier has no problem coping with the low signal voltage without the need for a transformer.)

During the past six years, I have transferred over 600 LPs to DSD using the 9TT cartridge, as well as enjoying it for day-to-day listening. I recently detected more background noise and distortion when playing LPs, and so I decided to replace it with a new one. I love the sound of the 9TT and I have no desire to change. But it brings up the question: how does one decide on which cartridge to buy, other than by reading reviews or consulting with experts? I doubt many dealers are willing to let customers home-audition cartridges, and the performance of a cartridge very much depends on how it matches with the rest of the record player as well as the phono preamplifier. Rather than take the risk of ending up with something I wouldn’t like, I went and bought another 9TT.

To be honest, I have been listening to tapes more than anything else nowadays, having accumulated more than 200 titles. Most of my tapes are copies of production masters, made for me by mastering engineers who operate or used to operate mastering facilities, and I have also bought commercial titles from The Tape Project, Analogue Productions, Horch House and Reel to Reel Tapes Russia. It is always interesting to compare the LPs and tapes of the same recordings. Having installed the new cartridge, I decided to look through my LP collection and re-evaluate the more interesting titles, some of which I have not heard for years or even decades.

I would like to share my findings with Copper readers as I go through my collection. This is not a “Best LPs” list in the vein of “The Super Disc List” that Harry Pearson began publishing in The Absolute Sound magazine (and which is still published today at various intervals). I find such lists useful in helping me discover new music, but I certainly do not confine myself to “audiophile” recordings. In fact, I almost never buy records unless the music interests me. Some of the recordings on my list rarely appear on the radar screen of audiophiles, but nevertheless have astonished me with their technical excellence. I have chosen the recordings for their sonic merit; I do not feel I am qualified to judge the merit of the musical performances and will therefore only make some passing comments on this aspect.

Why confine the scope of this survey to just analog recordings? One of my previous articles touched on the merits of analog and digital recordings. I was most actively buying records and learning about music at a time when digital recording was still in its infancy, and I have been too busy with the responsibilities of being a working adult and a parent in the past two decades to keep up with new recordings. However, I genuinely believe that most of the great recordings (in the classical repertoire anyway) were made between the early 1950s and the late 1970s. Classical music labels at that time had the financial resources to devote to recording projects, whereas nowadays, music has become a commodity with limited profit potential. During the analog age, recording engineers had to rely on getting everything right during the sessions, whereas it is all too easy nowadays to correct mistakes during post-production, but the result is never optimal. I also find the sonic results of the simple microphone techniques of yesteryear more desirable than that of employing multiple microphones, typical of modern digital recordings. Furthermore, most music nowadays is consumed on headphones, earbuds, car audio systems and computer speakers. There is just not much incentive for record producers to prioritize sound quality.

Readers need to understand that the sound quality of an LP does not necessarily reflect that of the recording itself. It is useful to reiterate the process of making an LP in order to understand the factors that can affect the sound quality. Before the widespread use of multi-track, sessions were recorded onto two-track or three-track tapes. Decca engineers typically used eight to 12 microphones, and mixed the inputs in real time onto two-track tape. At RCA and Mercury, three-track tape was used, and this was mixed into stereo during post-production. This is more desirable, because every extra track adds 3 dB of noise, hence the need to use noise reduction systems in multi-track setups, which are another potential source of signal degradation. If multi-track tape was used, this was usually mixed into stereo before editing.

Some companies might edit the session tapes directly, or make a copy for editing. The edited tape with all the splices is called an edited work part, and will then be transferred with the necessary corrections (frequency response adjustments, added reverb etc.) to create a master. Multiple masters, called safety masters, are often created for backup purposes. Again, 3 dB of additional tape hiss is added every time the tape is copied. A copy made using high-quality, well-maintained and properly aligned professional tape machines has barely-discernible differences from the original.

The studio master is then copied to make production masters, which are sent to mastering facilities in the different markets for LP and cassette production. The lacquer for producing LPs is usually cut directly from this master. The necessary compression, RIAA equalization and so on are usually applied during transfer from the tape to the cutting lathe, although another tape copy incorporating these changes is occasionally made. This is a crucial stage for ensuring the sound quality of the final product, but the engineer is sometimes constrained by commercial and practical considerations. For example, the length of the program might necessitate the use of compression in order to fit onto one side of an LP. While it makes no difference whether a reel of tape has 20 or 30 minutes of music, or even longer if one uses larger flanges, it makes a great deal of difference to an LP. The closer the groove is cut towards the center of the record, the higher the distortion. Groove width needs to be reduced, which means lower dynamic headroom. When faced with these constrains, the skill and experience of the mastering engineer come into play.

Once the lacquer is cut, it is sent to be electroplated with nickel to produce a negative image called the father. The father can be used to stamp records, with a limit of only 1,500 disks, but the sound quality starts to deteriorate long before reaching this number. In order to produce a larger quantity of records, the father is electroplated to create a mother, which in turn is used to create a number of stampers. Each step will result in a little loss in sound quality, which is why some audiophile labels release limited edition LPs (usually 300 to 500 copies) stamped directly from the father.

The quality of an LP therefore depends on the skill of the mastering engineer and the care he took to cut the lacquer. It depends on the quality of the work to create the stampers. It depends on the quality control process and rejecting substandard disks. It depends on the vinyl formulation used, and the age of the stamper used to produce that particular disk. On the second hand market, Decca LPs originally sold in the UK often command a higher price than their London-branded (the Decca trademark belonged to another company in the US) LP counterparts originally sold in the US. However, the Decca and London LPs have the same dead wax markings, meaning the same lacquer was used and the LPs were pressed in the same plants in England. Decca later moved their record production to Holland. Once again, for the same title, the Made in England LPs are usually more valuable, but I find some of the Made in Holland LPs can actually be sonically superior, probably because they were manufactured at a later date with a more advanced process.

On the other hand, to name another example, the Angel LPs sold in the US were made in the US, and are generally inferior to the equivalent Made in England EMI LPs.

For a long time, I had the impression that Decca recordings are far superior overall to EMI recordings. However, after having listened to some EMI master tapes and contemporary reissues, I have to revise my opinion. Decca recordings are still superior, but the margin is not so wide. I can only come to the conclusion that the LP production part of EMI was letting this side of the manufacturing process down.

In general, I find the recent audiophile reissues generally more consistent and are of higher quality than the original issues, since each production run is likely to be far smaller and more care is taken to preserve the best-possible sound quality.

Malcolm Arnold, London Philharmonic Orchestra – English, Scottish and Cornish Dances

Lyrita Recorded Edition SRCS 109

Since Harry Pearson’s Super Disc List has already been mentioned, we might as well start with one of his favorite LPs. I have to thank HP for helping me discover this record label. Lyrita was an independent English music label with a mission to promote British composers. It had released about 100 LPs before closing its doors, reemerging again several years later to market CDs of their catalog. The company did not have its own recording team, and outsourced its projects to Decca. The LPs were initially pressed by Decca, later by Nimbus, and finally by EMI. Many experts consider the Decca and Nimbus pressings superior to those by EMI. The sound quality of these LPs is consistently excellent. Most music lovers are probably familiar with British composers such as Holst, Britten, Elgar, Walton, Vaughan Williams and Arnold, but the Lyrita catalog also contains lesser-known works of these composers, as well as works of more obscure composers not found elsewhere. I bought a bunch of these LPs when the company held a stock clearance before ceasing business activities in the late 1980s.

The music on this LP is very accessible, perhaps a bit lightweight but quite endearing. You might have heard snippets of it on the radio or even on TV adverts if you live in the UK. Hearing it is one of those, “Ahhh, this is where it comes from!” moments. The sound is vintage Decca, with a wide soundstage, good separation, beautiful string tone and great dynamics. Is it “Best of the Bunch” as HP claimed? In my opinion, this LP is not amongst Decca’s highest achievements, and not even the best of the Lyritas. The low end can sometimes sound a bit bloated, which muddles the sound during the more complex passages. The string tone can also sound a bit homogenized at times. It is nevertheless an excellent recording overall. Being awarded “Best of the Bunch” by HP, one would expect this LP to have been reissued a million times. Strangely, it has never been reissued since its initial release. As it remains on the Super LP list, expect to pay three figures for a good copy. Chad, are you paying attention?

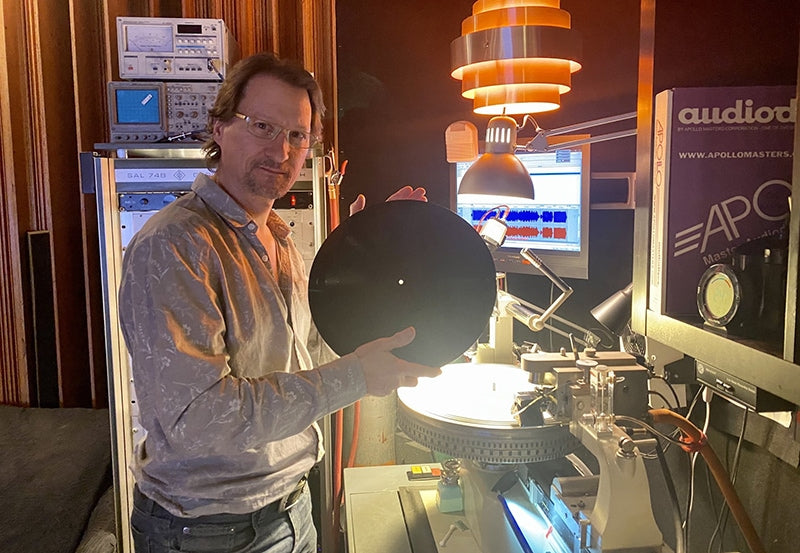

Header image: Greg Reierson of Rare Form Mastering. Photo courtesy of Greg Reierson.