Lou Reed passed away on Oct. 27, 2013 but interest in him remains high, as evidenced this past June by the opening of an exhibit at the New York Public Library (NYPL) for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center; the November vinyl release of his earliest, pre-Velvet Underground demos, and an early-December tribute commemorating the 50th anniversary of his breakthrough Transformer album.

What might be of special interest to readers of Copper is that renowned mastering engineer Bob Ludwig once told me Lou Reed cared more about sound than any other musician with whom he ever worked. When I finally had the opportunity to interview Reed in February 2003, after 25 years of trying, much of what we talked about was his search for sonic perfection.

“Mastering is such an astonishing experience,” Reed said, at his Soho, New York office for Sister Ray Enterprises. “The technology has improved in a staggering way. I was able to go back to all the old Velvet Underground records on up and really make them sound the way they’re supposed to sound.”

A few months later, BMG was releasing a two-CD retrospective, NYC Man. “I don’t like to listen to my old stuff. But when I do hear [older CDs], it’s only upsetting because you say, ‘If only I could do this, listen to that: Why didn’t they clean the vocal track? There should be more bass on this.’ If you made a [vinyl] record that’s 20 minutes long, you’ve lost bottom, you’ve lost volume. Then they made a CD of it and kept it that way. So you have these CDs floating around that have no known bottom.

There’s no reason for it – they’re just mimicking the vinyl. If you can go back and remaster it, as opposed to them – all they’re going to do is the minimum – you can address these problems, which is what I did.”

Reed clarified that “them” meant the record company. “Yeah, they’re just going to throw it in and reproduce it – badly. I’ve listened to some of those reproductions that they’ve done. It’s unbelievable how chintzy they are.”

Reed’s Stereo Binaural Quest

At the time of the interview, Reed was promoting The Raven, his mostly spoken-word rewriting of Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories and poems, utilizing the talents of actors including Willem Dafoe, Elizabeth Ashley, Amanda Plummer, and Steve Buscemi, amid sound effects. The Raven is closer in style to a radio drama of yesteryear such as Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds than a conventional rock album. In 2019, The Raven was released on three-LP vinyl for the first time for Record Store Day.

Lou Reed, The Raven, 3-LP album cover.

“It was very hard to do this – very complicated, complex, so many different levels,” Reed explained. “You couldn’t have done it without the use of computers. The music is analog, but the acting, the effects, the placement of the effects, you had to put it in a computer to move it around, hear if it works. The stuff really worked, trying to move things spatially. It was all about space, depth. I brought in every [music effects] toy I own.”

I asked whether the sound effects and spatial relationships that play with the listener’s imagination would have been better suited for a surround mix. Reed responded, “Yes, I would [still] like to do a 5.1,” although he preferred to instead mix The Raven in the stereo binaural system, a recording process developed by German recording engineer Manfred Schunke that Reed used on three albums in the late 1970s: Street Hassle, The Bells, and Live: Take No Prisoners.

“Play the whole thing for a head. [Binaural recording involves the use of microphones placed in the ears of a dummy head. When played back, especially over headphones, the sense of 3D realism can be startling. – Ed.] I’ve been obsessed with that for a long time,” explained Reed. “Now it works. We figured out what was wrong. It was a phasing problem. On the way to vinyl, something happened with phasing and the effect went away. But it’s back and is pretty astonishing. If you sit in the sweet spot, it’s amazing. That was 1978. I’ve waited 24 years to get a shot at this again.”

Reed said he “begged and pleaded” with the Warner top brass to give The Raven a binaural treatment, but to no avail. Still, Reed was pretty happy with the sonic qualities of what has been released. “[The Raven’s] stereo imaging is pretty large. You’ve got things coming at you from the back, diagonally. You don’t have anything coming directly in back of you, true.”

Reed was certainly on the right track given all the current attention currently on Dolby Atmos’ immersive audio experience.

The author’s autographed LP of Metal Machine Music and 8-track of The Velvet Underground Live at Max’s Kansas City.

Words & Music, Copyright 1965

While The Raven could be considered near-audiophile caliber for a two-channel CD in 2003, Light in the Attic’s (LITA) November 2022 vinyl release of Words & Music, May 1965 isn’t a high-fidelity recording by any stretch of the imagination – but it’s a historical landmark. Words & Music May 1965 features some of Reed’s earliest recordings, made from a reel-to-reel tape found in his office after his death, in a still-sealed package that he mailed to himself for the “poor man’s copyright” protection.

Lou Reed, Words & Music 1965, album cover.

Accompanied by future bandmate John Cale while both were employed by the low-budget label Pickwick, these decidedly lo-fi recordings of Reed’s formative years show a folkie side that rarely emerged in his later music.

The deluxe LITA set includes two 45-RPM 12-inch LPs, pressed on HQ-audiophile-quality 180-gram vinyl at Record Technology Inc., plus a bonus 7-inch disc, housed in its own unique die-cut picture sleeve and manufactured at Third Man Pressing. The set includes the only vinyl release of six previously-unreleased bonus tracks, including a cover of Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” an instrumental version of “Baby Follow Me Down,” which Dylan covered on his debut album, and a doo-wop serenade recorded in 1958 when the Reed was just 16 years old.

Sylvia Reed, Lou’s second wife in a relationship that spanned 17 years that included her managing Lou Reed’s business affairs, recently told me she knew of the 1965 tape, and presumably he did too. I find it interesting that Lou didn’t offer this early music when the Velvet Underground five-CD boxed set, Peel Slowly and See, was released by Polydor in 1995, although the set included some early Velvets demos and original folkie songs.

In any case, Words & Music was released in conjunction with the New York Public Library exhibit, titled “Caught Between the Twisted Stars,” which closes on March 4, 2023. Digital archives are available to researchers who require an in-person appointment.

Transformer Celebrated 50 Years Later

As much as Reed strived for sonic perfection in the studio, he loved performing live and hearing other people sing his songs, another thing he mentioned during my interview with him.

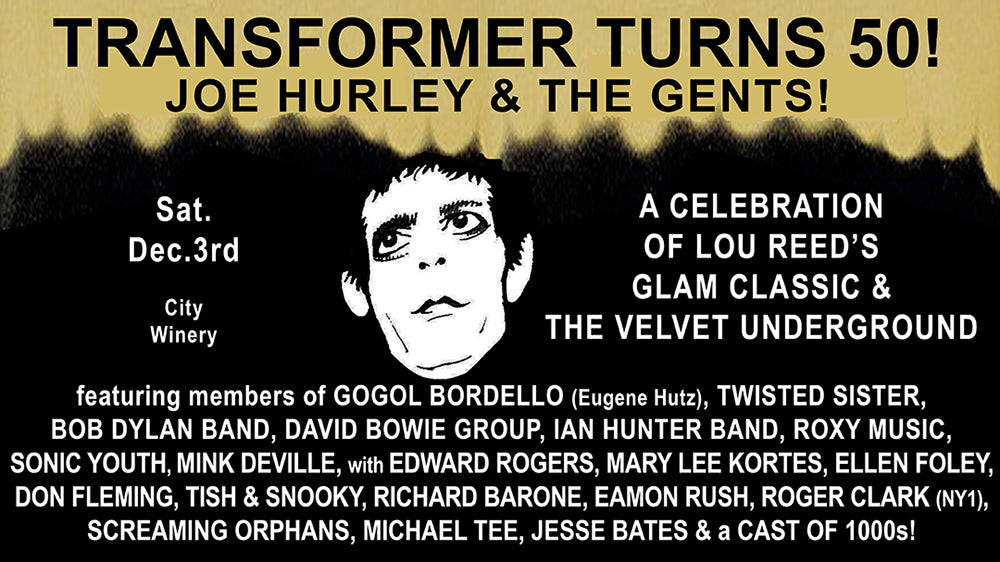

Speaking of which, another New York institution, Joe Hurley, organized “Transformer Turns 50: A Celebration of Lou Reed’s Glam Classics and the Velvet Underground” on December 3, 2022 at New York’s City Winery.

London-bred Hurley’s baritone vocals have been a fixture on the NYC scene for more than three decades, and he’s mounted similar tributes in recent years to Marc Bolan/T.Rex, and to Irish music, celebrating Hurley’s heritage. He might be best known, however, as the reader of two-thirds of the audiobook for Keith Richards’s memoir, Life; the first third was read by Johnny Depp with a cameo from Keith himself at the end. It won Audiobook of the Year in 2011 from the Audio Publishers Association.

The band: Don Fleming, JF, Joe Hurley, Steve Holley (obscured on drums), Edward Rogers, Sal Maida, Stan Harrison, and Kenny Margolis. Courtesy of Melani Rogers.

The band: Don Fleming, JF, Joe Hurley, Steve Holley (obscured on drums), Edward Rogers, Sal Maida, Stan Harrison, and Kenny Margolis. Courtesy of Melani Rogers.

Joe Hurley performing at the “Transformer Turns 50” event. Courtesy of Jeff Kaufman.

It was Hurley’s original material that piqued my interest almost three decades ago with original compositions like “Amsterdam Mistress,” a heartfelt ballad of a brief encounter while visiting abroad, which reminded me of Ian Hunter’s “Angel of Eighth Avenue” on Mott the Hoople’s Wildlife. Prior to the Lou Reed tribute, Joe Hurley and the Gents played a 40-minute set of his own material, including “Amsterdam Mistress.” It was great to hear those songs again.

Speaking of Mott the Hoople, David Bowie produced their breakthrough All the Young Dudes in 1972, the same year that he and Mick Ronson also produced Transformer, Lou’s breakthrough as a solo artist.

Hurley’s all-star band was anchored by the rhythm section of drummer Steve Holley, who’s played with Ian Hunter for 20-plus years, and Sal Maida, who played bass for Roxy Music’s live shows in 1973 and 1974.

Edward Rogers co-hosted the two-hour concert with Hurley, with whom he kicked off the concert by singing in unison on the Velvet Underground’s “We’re Gonna Have a Real Good Time Together.”

Another featured performer, Sonic Youth co-founder Lee Ranaldo, took the lead vocals on the Velvets’ “Rock and Roll,” which he mentioned he played often while paying dues before Sonic Youth made it big.

Other highlights included Ellen Foley making “Perfect Day” a torch ballad, and Ukrainian expat Eugene Hutz, leader of Gogol Bordello, belting out the well-chosen “Vicious.”

Video courtesy of Stephen Joy.

Hurley’s house band was anchored by the rhythm section of Roxy Music bassist Sal Maida and regular Paul McCartney drummer Steve Holley. Playing guitar throughout the set, Don Fleming, the primary curator of the NYPL Lou Reed archive, faithfully performed a Velvets outtake, “Temptation Inside Your Heart,” which captured all the nuances that only an aficionado of the band would appreciate.

Always on the scene for these types of gigs, former Bongos front man Richard Barone played “White Light/White Heat.” Screaming Orphans came in from Ireland to sing a Celtic-styled “Goodnight Ladies.”

Closing out the show: (L to R) JF, Sal Maida (sitting), Snooky, Tish, Joe Hurley, Stan Harrison, Kenny Margolis (partially obscured). Courtesy of MurphGuide.com.

Hurley kept “I’m Waiting for the Man” for himself, and to close the show, the cast of characters vamped along with him on “Walk on the Wild Side,” even managing to exceed the 16 minutes and 54 seconds length of Lou’s Live: Take No Prisoners.

Video courtesy of George Rush.

If you remember, the opening seconds of that binaural-produced 1978 album starts off with him taking out a package of cigarettes and lighting a match that gives the listener the feeling that you’re on stage with Lou at the Bottom Line. The Light in the Attic 1965 demo tapes record is labeled as “Vol. 1,” and I hear through the grapevine that there’s much more in the archives that will keep us Reed fans enthralled.

Part of Lou Reed's personal record collection, on exhibit at the New York Public Library. Courtesy of Larry Jaffee.

Part of Lou Reed's personal record collection, on exhibit at the New York Public Library. Courtesy of Larry Jaffee.Header image: “Transformer Turns 50″ event advertisement, designed by Cliff Mott. Courtesy of Joe Hurley.