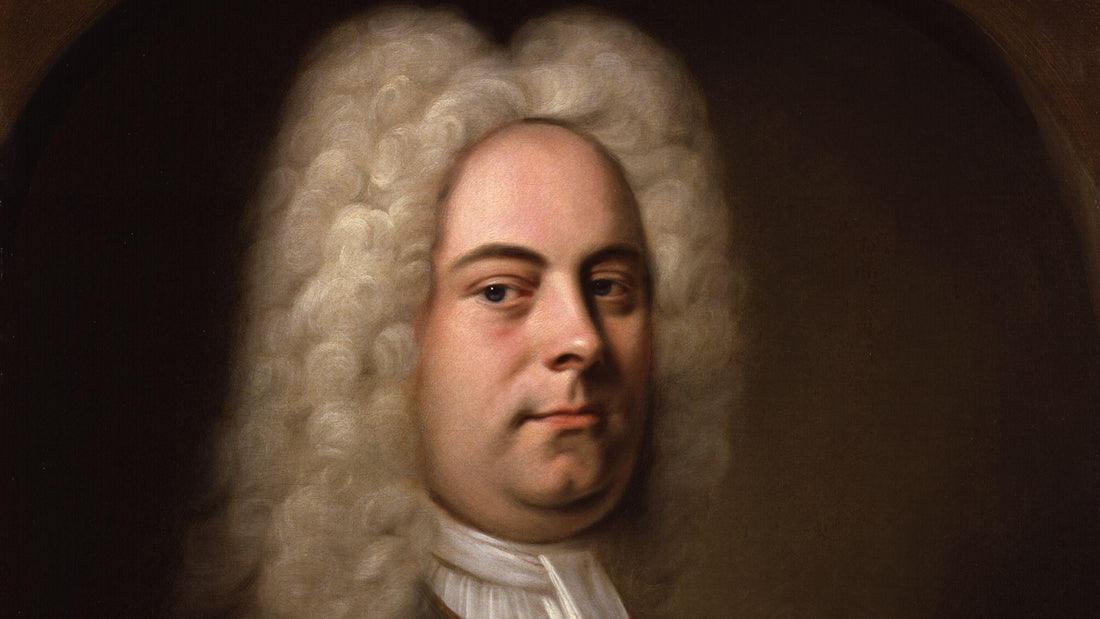

Nearly all the great creative musicians were good collaborators. It obviously worked for George Frideric Handel (1685–175). Eccentric country squire Charles Jennens (1700–1773) wrote several libretti for him; Handel set them to music as the oratorios Saul, L’Allegro, Belshazzar, and—most famously—Messiah. Jennens does not appear to have been a perfect gentleman, although “gentle” he surely was, i.e., a man of independent means and cultivated tastes. Infamously self-regarding and fond of ostentation, Jennens acquired the epithet “Suleyman the Magnificent” from Samuel Johnson himself.

As a litterateur, he actually was magnificent. Many a member of the 18th-century landed gentry became a “man of letters” as a respectable fallback, but that doesn’t mean they all lacked talent. Thomas Morell, Newburgh Hamilton, and other Handel librettists knew what they were doing, and Handel was only too glad to receive their “word-books.”

Jennens and Handel have been described as close friends. Perhaps they were. Handel certainly found Jennens valuable, and Jennens must have sensed that his best shot at immortality lay in working with Handel. Apart from his literary skill, Jennens’ self-assured frankness, bolstered by privilege, was exactly what Handel needed. Here’s what Jennens wrote to a friend in September 1738 during the gestation of Saul:

Mr. Handel’s head is more full of maggots than ever. I found yesterday in his room a very queer instrument which he calls carillon (Anglice, a bell) and says some call it a Tubalcain. . . . ‘Tis played upon with keys like a Harpsichord and with this Cyclopean instrument he designs to make poor Saul stark mad. His second maggot is an organ of £500 price which (because he is overstocked with money) he has bespoke of one Moss of Barnet. . . . His third maggot is a Hallelujah which he has trump’d up at the end of his oratorio since I went into the Country, because he thought the conclusion of the oratorio not Grand enough; tho’ if that were the case ‘twas his own fault, for the words would have bore as Grand Musick as he could have set ‘em to: but this Hallelujah, Grand as it is, comes in very nonsensically, having no manner of relation to what goes before. And this is the more extraordinary, because he refused to set a Hallelujah at the end of the first Chorus in the Oratorio, where I had placed one and where it was to be introduced with the utmost propriety. [underlining added]

About that “Hallelujah,” Jennens was quite right. Handel restored it to Act I, where Jennens had put it as a climax to general rejoicing, Goliath having fallen. After Jennens’ visit, Handel also restructured Act III (into which he had planned to paste chunks of his Funeral Ode for Queen Caroline) by depicting inter alia Saul’s desperate encounter with the Witch at Endor, who summons forth the Ghost of Samuel. It is one of the most haunting moments in Baroque drama. (YouTube audio: No. 73 at 7:06.)

Jennens later took offense at the slapdash manner in which Handel set Messiah. His displeasure grew when the composer took that show on the road, premiering it in Dublin. After the oratorio’s (mixed) London reception, he wrote:

[January 1743:] Handel has borrow’d a dozen [pieces of music sent by a friend, Edward Holdsworth] & I dare say I shall catch him stealing from them, as I have formerly, both from Scarlatti & Vinci. He has compos’d an exceeding fine Oratorio, [Samson], with which he is to begin Lent. His Messiah has disappointed me, being set in great hast, tho’ he said he would be a year about it, & make it the best of all his Compositions. I shall put no more Sacred Words into his hands, to be thus abus’d.

[April 1743:] Messiah was perform’d last night, & will be again to morrow. . . . Tis after all, in the main a fine Composition, notwithstanding some weak parts, which he was too idle & too obstinate to retouch, tho’ I us’d great importunity to perswade him to it.

[September 1743:] I hear Handel is perfectly recover’d [from a stroke], & has compos’d a new [Dettingen] Te Deum & a new Anthem. . . . I don’t yet despair of making him retouch the Messiah, at least he shall suffer for his negligence; nay I am inform’d that he has suffr’d for he told Ld. Guernsey that a letter I wrote him about it contributed to the bringing of his last illness upon him; . . . This shews that I gall’d him: but I have not done with him yet . . .

Holdsworth scolded him for this:

[October 1743:] You have staid too long [in Leicestershire] already; it has had an ill effect upon you, and made you quarrel with your best friends, Virgil & Handel. You have contributed, by yr. own confession, to give poor Handel a fever, and now He is pretty well recover’d, you seem resolv’d to attack him again. . . . This is really ungenerous, & not like Mr. Jennens. Pray be merciful; and don’t you turn Samson, & use him like a Philistine . . .

Apparently this shut him up. Handel scored resounding successes with two secular oratorios, Semele and Hercules, and then renewed his collaboration with Jennens, writing:

[June 1744:] It gave me great Pleasure to hear Your safe arrival in the Country, and that Your Health was much improuved. I hope it is by this time firmly established, and I wish You with all my Heart the Continuation of it, and all the Prosperity. As You do me the Honour to encourage my Musical undertakings, and even to promote them with a particular kindness, . . . Now should I be extreamly glad to receive the first Act, or what is ready, of the new Oratorio with which you intend to favour me. . . .

The “new Oratorio” was Belshazzar, at which Handel worked diligently that summer, continually pressing Jennens for more material. All was forgiven.

* * *

Here I could switch to the 21st century and survey more recent collaborations, but everyone has beaten me to it. See, for example, Thomas Brothers’ Help! The Beatles, Duke Ellington and the Magic of Collaboration, now getting strong reviews. (For Dominic Green’s longer discussion in the WSJ, you’ll need a subscription. Or you could just buy the book.)

The landscape has certainly changed. In Nashville, you can’t sell a song these days unless you’ve co-written it. If you’re Beyoncé, you book two stories of a hotel, fill it with creative specialists (a beats person, a hooks person, some lyricists), then blend, season, and bake: there’s your new LP. What if your minions quarrel? Well, they work for you, so they’ll just have to keep it positive.

Here I offer one other golden example of modern collaboration: Marnie. The 1961 novel by Winston Graham is now an opera, which means it’s become a tale told by many. Director Michael Mayer, Tony winner for Spring Awakening, suggested the property to composer Nico Muhly, who enlisted librettist Nicholas Wright; they quickly brought in set designer Julian Crouch, costumer Arianne Phillips, and choreographer Lynne Page, all working at the top of their game.

Of reviews available online, the most balanced assessment comes from Alex Ross of the New Yorker. He gets the big picture, sympathizes with the attempt to tell this story from a female protagonist’s point of view, and describes key scenes with an unmatched command of musical detail. His plot summary:

Marnie is a sociopathic young woman who routinely invents new identities, steals from her employers, and then vanishes. The story is, on its face, a stereotypical male fantasy of female neurosis: the Hitchcock version borders on misogynist hysteria.

In the past Muhly’s music has struck me as derivative. Yet I loved Marnie when I caught it at the local multiplex. Many cooks made thin broth work! You could say it worked precisely because of its many cooks: Marnie is that rarity, a perfectly engineered musical clock. The dazzling stage movement (choreography doesn’t begin to describe it), the chic Technicolor outfits of the “shadow Marnies”—indeed, the concept itself—the brilliant orchestral writing, the singing and acting of mezzo-soprano Isabel Leonard and her colleagues—all function effectively, and more importantly, to equal effect. If you’re looking for an opera with memorable music, keep looking. But if you are looking for a riveting evening of theatre in which every element, including the music, makes a crucial contribution, get the inevitable Blu-ray. Or see it at the Met when it’s revived, as it should be.

Closing thoughts: Wright’s libretto has been disparaged as verbose and commonplace, but I heard characters who spoke with authentic voices. The banality of the dialogue perfectly evoked the limited viewpoints and crippled insights of this late-‘50s scenario. Its true cinematic father-figure is not Hitchcock but Douglas Sirk, who was directing Written on the Wind and Imitation of Life just as Graham was writing Marnie. For years Sirk was dismissed as a skilled hack, master of a negligible genre, the “woman’s movie.” Then Godard, Sarris, Ebert, James Harvey and others woke up to what he was doing—with camerawork, art direction, lush color—and to the symbolism and irony it (barely) masked. Sirk’s characters could behave badly and show little self-awareness. But millions of moviegoers recognized these women and their social entrapment, and that recognition opened wellsprings of emotion buried deep within.

As Marnie the opera ends, Marnie herself experiences a liberating epiphany. Law and circumstance have closed in. It’s almost too late. Nevertheless she owns this moment, and Muhly gives her just enough new musical color to suggest triumph, not tragedy. Marnie in its final scene again offers us more than the sum of its parts. It’s a phenomenal product of collaboration.