Ken Kessler recounts the hardware phase of his re-entry into the world of open-reel tape, as a cautionary tale and a guide-of-sorts to help you maintain your sanity.

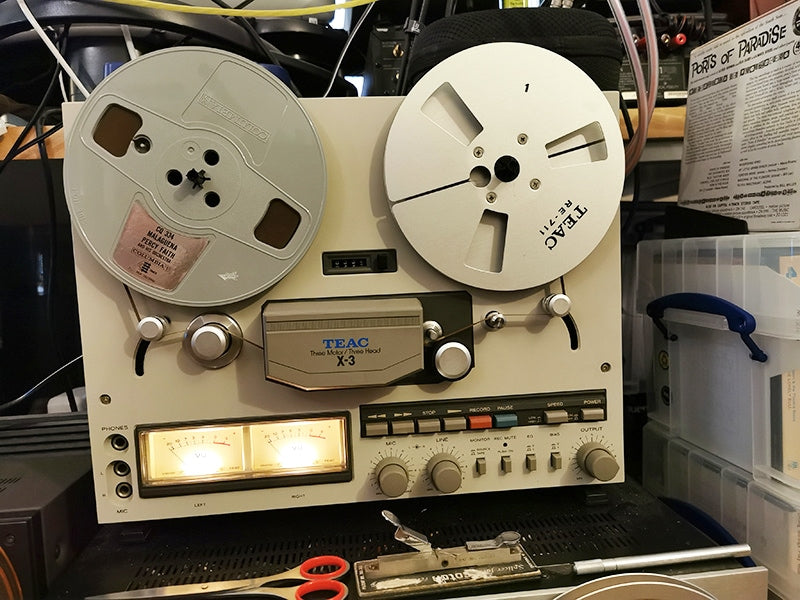

As inveterate audiophiles, I have no doubt that a goodly percentage of Copper readers scour eBay on a regular basis for all manner of hi-fi-related items. I used to shun eBay, but am now so invested in it that one individual suggested I need an intervention. Not only have I now acquired 2,200 used pre-recorded tapes from the site, I have also bought at least one tape deck – a near-mint, boxed TEAC X3 for under £300/$410 – and countless spools of leader and tail tape, splicing tape, a few splicing blocks and more. It is scarily addictive.

But here’s the reality check: the reel-to-reel tape revival is not in my head, not mere wishful thinking on my part, as I have experienced the explosion first-hand. As synecdoche, I will tell you of an obscure tape, which I will not name, which popped up on eBay. I figured, judging by the values of other tapes, that the maximum it would sell for was $20, plus the same again for shipping to the UK. (Yes, the postal system, eBay, and others are the new highway robbers.) Said tape ended up selling for $240. That’s Beatles/Led Zep/Miles Davis money for a band few have heard of, let alone remember.

Inflation had hit the revival. Hard. This shock in the escalation in prices of tapes obviated the need for the aforementioned intervention. I realized, after looking at the 70 or so filled Really Useful Boxes I use to store my tapes, which hold 19 each, that I was not only no longer financially able to continue, as a pensioner in a country where gas is now over $10 a gallon, but that I had more tapes than I actually needed. Of course, there are others I would love to own, like the Beatles open-reels missing from my collection, but I am supposed to be down-sizing, not burdening my wife and son with more sh*t to clear out when I croak.

TEAC X-3.

But such is the way with open-reel tape and the quest I found myself undertaking after Bob Ludwig and the late Tim de Paravicini so convincingly informed me of its superiority. That I already had four tape decks in storage, but only 20 or so tapes, at least provided an advantage to my starting point, unlike someone coming to open-reel tape from cold. I have learned, too, that numerous audiophiles above a certain age own reel-to-reel tapes and decks which they haven’t used in years, and never disposed of in some moment of madness. Call it a (tape) head start.

So equipped, I ended up swapping three of my decks for other machines. I then bought three bangers and I now have seven or eight. Thus armed, I can play NAB and IEC tapes, ¼- and ½-track, and at the three speeds of 3-3/4 ips, 7-1/2 ips and 15 ips, as well as the handful of modern 15 ips/1/2-track pre-recorded tapes on 10-inch spools – full disclosure: reviewer samples – which are way beyond my means.

Why so many machines? Easy: I’m a hoarder and a reviewer, and I use them as required, e.g. I bought a nice TASCAM 22-2 1/2-track machine at the UK’s AudioJumble, which I use to clean up my pre-recorded tapes, ones that might have been sitting for 60 or more years. I’ll get to that procedure in the next installment.

What I kept of the four machines in storage is the ReVox G36, hot-rodded by Tim de Paravicini. I must point out here that I only use the record facility to recycle the hundreds of home-recorded tapes which invariably get mixed in with the pre-recorded tapes. Again, I will get to that next time. But the de Paravicini-modified deck is my grail.

As this G36 is 1/4-track and plays 3-3/4 ips and 7-1/2 ips, it is my go-to machine for serious listening for probably 90 percent of the pre-recorded tapes I have purchased. The other 10 percent are early commercial 7-1/2 ips/1/2-track tapes, which pre-date the move to 1/4-track circa-1960, gems like the remarkable Capitol titles from Jackie Gleason, and original cast Broadway and soundtrack tapes. The ReVox is, after Tim gutted all the unnecessary circuitry, one of the best-sounding playback decks I have ever used. The only downside is that it contains so many tubes it is almost too hot to touch after four or five tapes – and I listen in eight-hour sessions.

When you consider that most pre-recorded tapes, bar classical titles, average only 15 minutes per side, you have some idea of how I managed to curate 650 tapes over the past three years while still leading the rest of a relatively normally life, COVID-19 notwithstanding. Lockdown, however, has facilitated, on a typical day while writing as my career demands, that I can easily listen to 10 or 15 tapes at a go. Who knew that I would ever learn to savor Mantovani, Percy Faith, Jerry Vale, Rosemary Clooney, 101 Strings, Ray Conniff, Steve and Eydie, the Baja Marimba Band, Enoch Light, Billy Vaughn, Andy Williams, or Robert Goulet?

If the G36, then, is reserved for high days and holidays, what do I use for regular listening, and how did I acquire the machines? Here’s where the newcomer to open-reel’s mettle is tested, let alone his or her budget, perseverance and temper. As my listening is split between two rooms – the section of the lounge where I write and my listening room where the reviewing system resides – each houses a number of machines to accommodate all the tapes bar the 10-inch spools, which stay in the studio with the high-end set up.

My day-to-day decks, because I spend so much time at my desk, are the aforementioned TEAC and TASCAM models, which are actually the same basic machine, and a beloved Pioneer RT-707, all only able to accept 7-inch spools. The TEAC is the domestic 1/4-track, 3-3/4 ips/7-1/2 ips deck, while the TASCAM in charcoal grey is the 1/2-track version operating at 7-1/2 ips and 15 ips. I use the TEAC and Pioneer for listening, and the TASCAM for the initial play-through of tapes which haven’t seen action in decades. As you can imagine, I go through head cleaner and pinch-roller cleaner like a wino on Ripple.

TASCAM Model 22-2.

Then we come to the big guns, which were the results of trades to a recycler of tape decks. I parted with two 1/2-track ReVox G36s, a never-used Tandberg T20 and a “cooking” cheapo Sony I had picked up for £50. The reference machines include an Otari MX5050 and a Technics RS-1500 which are now my most-used decks because they play 3-3/4 ips, 7-1/2 ips and 15 ips 1/4- and 1/2-track tapes at the flick of a switch (though the Technics is NAB-only while the Otari has EQ for NAB and IEC/CCIR).

Partly out of homage to Tim de Paravicini, I have a Denon DH-710 – the machine which Tim played for me in Tokyo and which started me on this adventure; it matches the flexibility of the Otari and the Technics, but minus 3-3/4 ips. It just may be the best-sounding machine I have ever used, and I could never hope to choose between it and the modified G36.

Pioneer RT-707.

In every case, I have been blessed/lucky. Tim had serviced the G36 a few years ago – we lost him last December. Crucially, I am fortunate enough to have access to the single most important element of using reel-to-reel in the 21st century: an open-reel maven who serviced my Pioneer, Otari, TASCAM, Denon and Technics machines; the TEAC was fine straight out of the box.

What I am about to say – and this will have resonance with a friend who had the misfortune of buying a Technics RS-1700 which swiftly failed and needed a now-unobtainable IC – is not designed to upset you. But just as it is obligatory for the rabbi faced with someone hoping to convert to Judaism, I want to dissuade you before you take the leap lest I feel your wrath when the residue hits the heads.

Prices are climbing like Rolexes at auction. The best machines have DOUBLED in price in under two years. If you can find a mint Pioneer RT-707 – one of the nicest 7-inch machines to use regardless of any tweak tendency or snobbery (I adore mine) – for under $1,000, grab it. A Technics RS-1500 for under $2,000? A steal in today’s market. TEAC 1000s and 2000s, or X3/X7/X10, a ReVox A77 or B77, the better Sonys or Akais – all are safer bets than ex-studio/semi-pro machines, simply because of the wear-and-tear of tape decks used 24/7/365. And if you can afford one of the excellent rebuilds from US or German specialists, so much the better.

Further dissuasion: If you do not have either the skills yourself to service, tune and/or rebuild machines, or you lack access to a genius tape deck savior, or – failing those – enjoy the deepest of pockets, don’t even consider getting an open-reel deck, unless you plan to use it for ballast for a boat or as a doorstop.

In Part Three, KK explores the tape situation.