At the risk of courting lawsuits from retired octogenarians, I find myself unable to resist attacking the easiest of targets: record labels. To be more precise, the major labels circa 1958/9 to circa 1985. The “circa” is because I don’t know the exact dates when the record labels switched en masse from 1/2-track to 1/4-track for pre-recorded tapes, nor when they moved from 7.5 ips to 3.75 ips (for the less-prestigious titles, i.e., non-classical). If there are still alive any record company executives, or more likely, record label bean-counters, who were responsible for these reductions in quality, they are welcomed to rationalize them. Hate e-mails to the usual address, please.

[NOTE: 1/2-track and 1/4-track are generally used interchangeably with 2-track and 4-track, but in the context of pre-recorded tapes, the former tapes play in one direction, using the full width of tape for two channels, the latter being reversible and playing in stereo in both directions. In the context of professional use, however, 4-track means four channels played in one direction.]

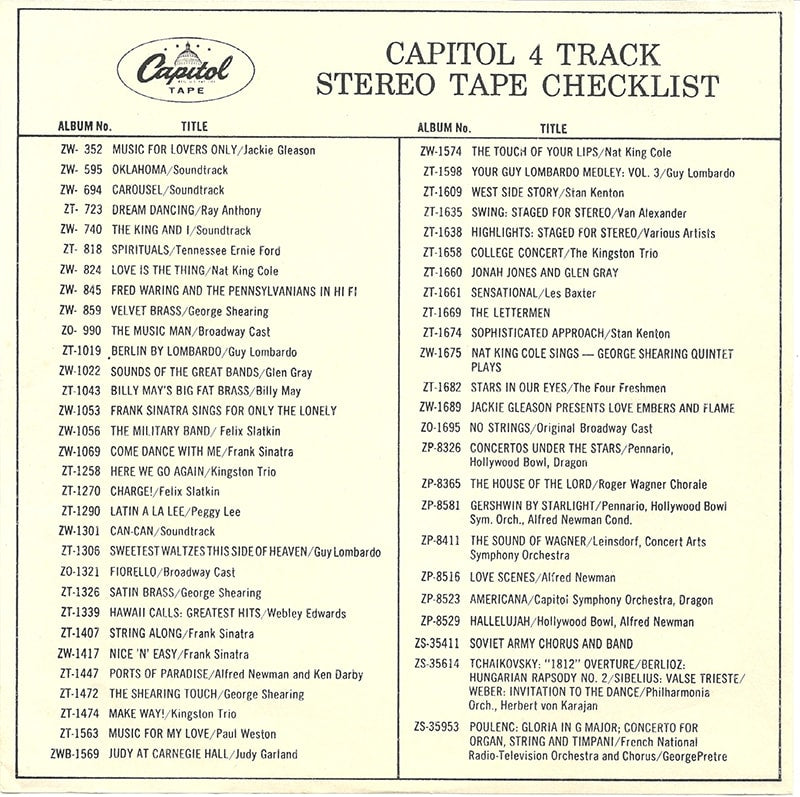

Early Capitol single-sheet 4-track catalog.

What brought about this issue’s ire, or more accurately disgust, is the stage at which I now find myself during my curating of over 2,500 vintage tapes. Again, to pre-empt those AES/BAS types who will find my sampling far too small to be of any worth – what would make them happy? – I admit that having now dealt with 1,800 of the tapes is hardly a definitive study. But if any numbers might support my argument, the number of labels involved comprises five or six which we would call “audiophile,” e.g., Livingston, and 25 or so mainstream names such as RCA, Capitol, Mercury, etc.

More numbers: Of the 1,800 tapes so far re-spooled, cleaned up, played, fitted with leader and tail, boxes repaired, while not counting duplicates or those thrown out as beyond salvation, there are more than 1,250 different albums. They span the earliest days of commercial, pre-recorded tapes – probably 1953-4 – with the newest tapes having been released in the mid-1980s.

Despite combing websites such as Discogs, Wikipedia and others, which do their best, this lack of precision regarding release dates is due to the vast majority of tapes having no dates printed on them whatsoever. And I mean vast, like 97 to 98 percent are completely devoid of the sort of basic information found on the corresponding vinyl LP releases. Moreover, using catalog numbers for chronological sequencing doesn’t work either, as the open-reel tapes were not necessarily released in the same order as the original vinyl albums, regardless of genre or the artists’ status.

What became shockingly evident over the past five years’ research is how shabbily the record labels behaved. Doh – no surprises here for anyone who has read any musicians’ biographies, or worked in the record biz. [Might I steer you to fellow Copper contributor Jay Jay French’s recent, illuminating tome, Twisted Business: Lessons from My Life In Rock ‘n’ Roll?] The horror stories are legion, and I don’t just mean the gonif labels and managers that ripped off everyone from Nina Simone to Tommy James to the Small Faces to just about every blues singer recording before the 1970s.

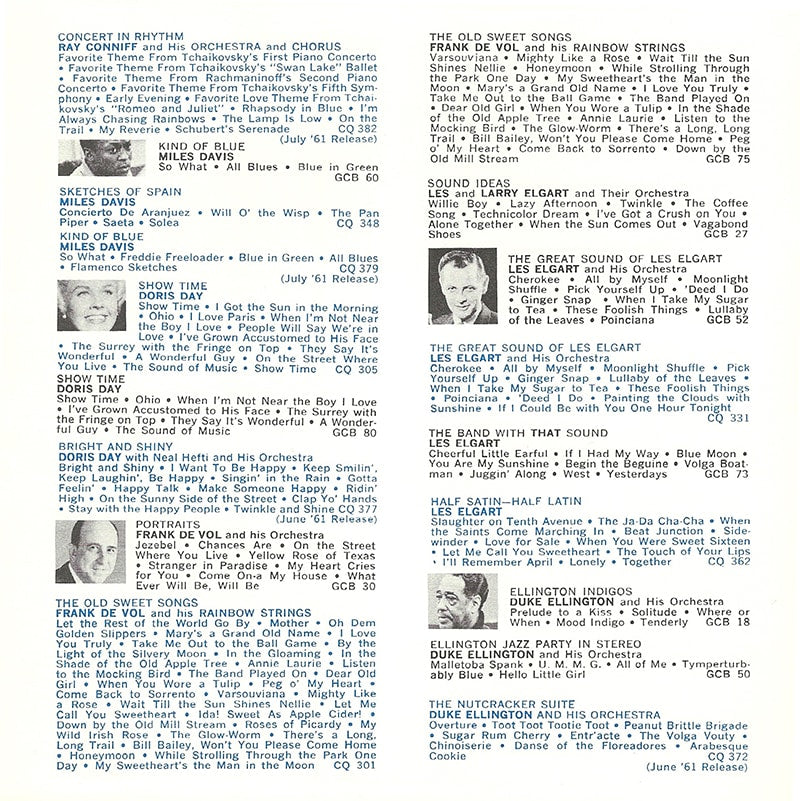

Columbia’s catalog from 1961 showing 2-track tapes in black and 4-track tapes in blue.

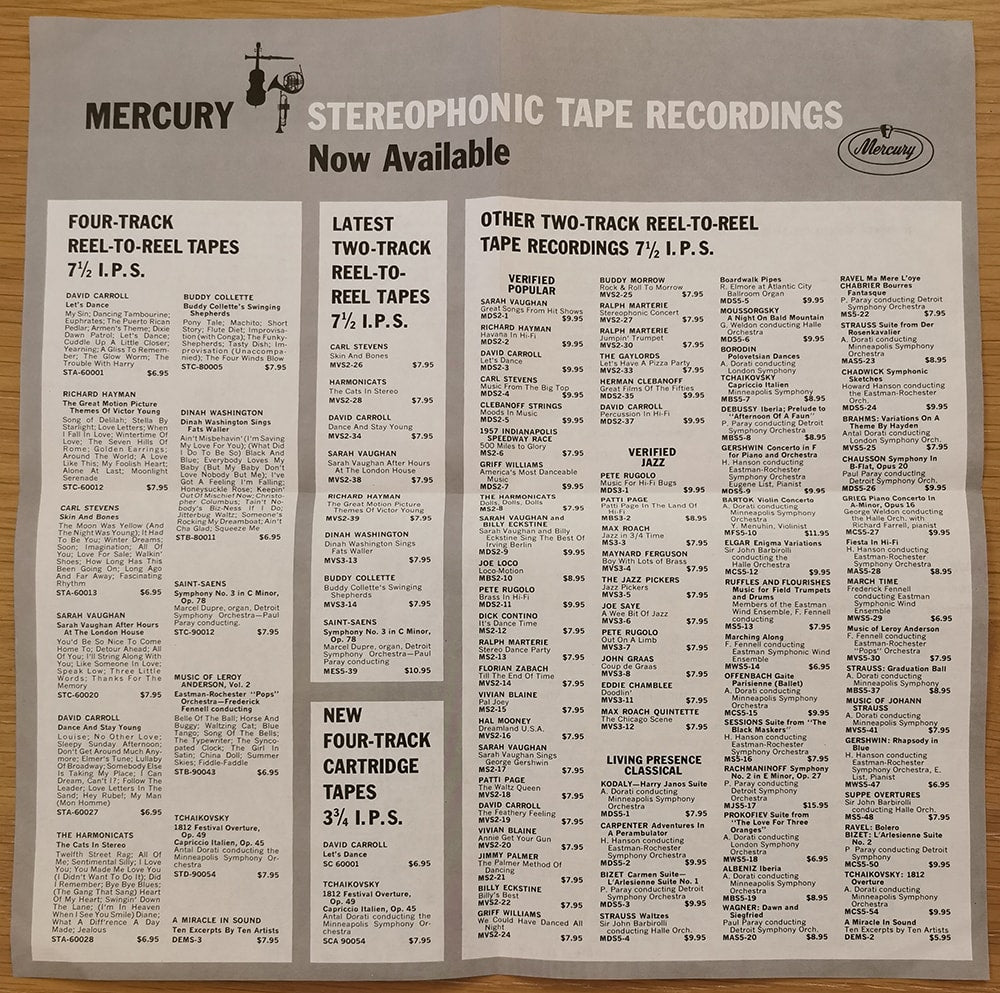

Inside the Mercury catalog – note the price differentials and track listings.

While screwing customers isn’t the same as screwing the musicians, what makes this irksome enough to rank with many of the labels’ malfeasances is pricing. Open-reel tapes were premium purchases, even when later reduced to their lowest quality by the end of the format’s existence in the 1980s. It also explains why the rock audience – usually under-25s with little disposable income – bought vinyl LPs instead of reel-to-reel tapes.

To put the ticket prices into context, note that prerecorded tapes typically sold for 50 percent more than LPs, and often double. More frightening (and this also tells you LPs were not exactly cheap 60 years ago), a tape selling for $12.95 in 1959 is equivalent to $122.19 in today’s money. Yes, approaching One-Step prices. So ask yourself this: Would you be happy if Mobile Fidelity or Analogue Productions packaged their deluxe (respectively) One-Step and UHQR releases in standard, thin cardboard sleeves, devoid of any liner notes? No, you would not. Those deluxe LP series are the 2022 equivalent of open-reel tapes of 60 years ago, but the latter certainly did not receive the same luxury treatment.

Which brings us to the evidence that is the easiest to dispatch: the physical lowering of quality over the format’s three decades, from the tapes themselves to their packaging. If you were simply to examine the spools and boxes of a 1950s tape with those from the following decades, you would, as I have, easily detect a palpable cheapening of both. The boxes’ cardboard and the plastic spools within grew thinner, cloth hinges disappeared – even the printing quality on the boxes dropped, something you can discover by comparing early and later releases of tapes which never left the catalogues, e.g., the soundtrack to South Pacific.

What I cannot comment on is the quality of actual tape stock, which I will leave to those of you who can spot the difference between Scotch and Ampex at 50 paces. (Oh, do I wish Tim de Paravicini was still with us …) As the more recent tapes obviously have the benefit of their youth to account for their survival, I can only surmise that the 30-year-older tapes I have from the early audiophile labels, as well as the 1950s/1960s releases from the major labels, can attribute their surviving just as healthily thanks to the tape quality. Yes, the tape stock on any 1958 Jackie Gleason release on Capitol is as free of shedding and print-through as any from the 1980s.

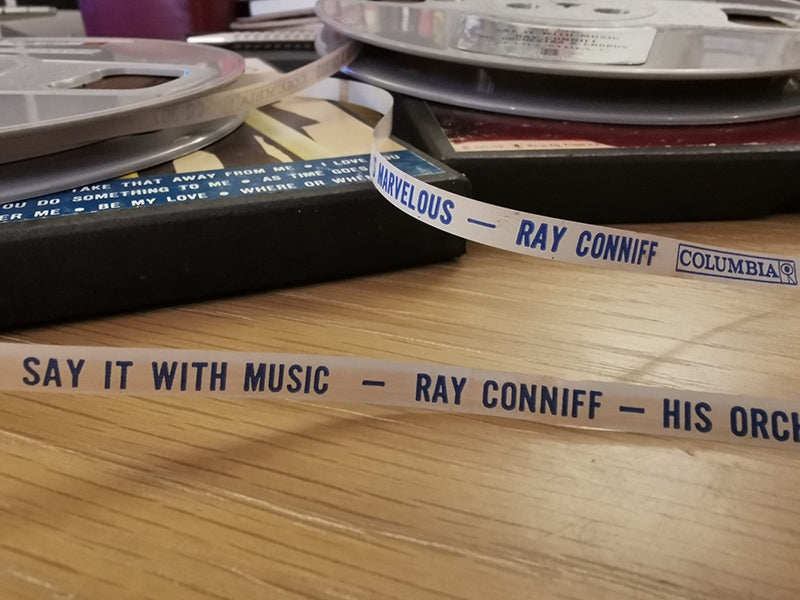

Still mystified by the lack of leader tapes and tails, I find it ironic that the worst commercial tapes ever released – the abysmal 5-inch-spool British tapes discussed in earlier installments (see my article in Issue 152) – were, to their credit, fitted not just with leader and tail but with plastic retaining clips. Moreover, the leader tape also had the artist’s name and album title printed on it. But, to indicate that the US pre-recorded tapes once were models of similar quality, I have discovered a couple of Ray Conniff albums in my haul of tapes and one or two 1950s soundtracks with printed leader tape. But they are the rarest of exceptions, and I cannot contain my surprise when finding one.

Labeled leader tape.

As for my belief that leader and tail were discarded early on by the labels, I came to this conclusion having now acquired at least eight still-sealed tapes, from assorted labels and price levels, dating from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s. All of them lacked leader tapes, the starting tape ends stuck to the spool with a small sticker instructing its removal before play.

Even more depressing is how the labels short-changed customers paying extra for 1/2-track tapes when they were available on both 1/2-track and 1/4-track. A particularly odious trick was that some 1/2-track versions, regardless of price, had shorter playing times, losing as many as four or five songs compared to the 1/4-track tapes, which played in both directions and therefore used less tape. Would it have killed the labels to provide more tape on the 1/2-track versions so they could include all the songs?

This barely scratches the surface, and I am not yet predisposed toward, say, playing the five different versions I have of South Pacific, The Sound of Music, or others which were reissued repeatedly, in order to gauge any possible drops in sound quality. There can be no bigger shocks than what I had already experienced, when comparing 1/2-track and 1/4-track releases of the same tiles, as well as the same album’s release in both speeds (e.g., the Beatles). No, nothing now can surprise me when it comes to the record labels’ utter contempt for both sound quality and their customers.

Hmmm … I just realized that only one letter differentiates “label” and “libel”…

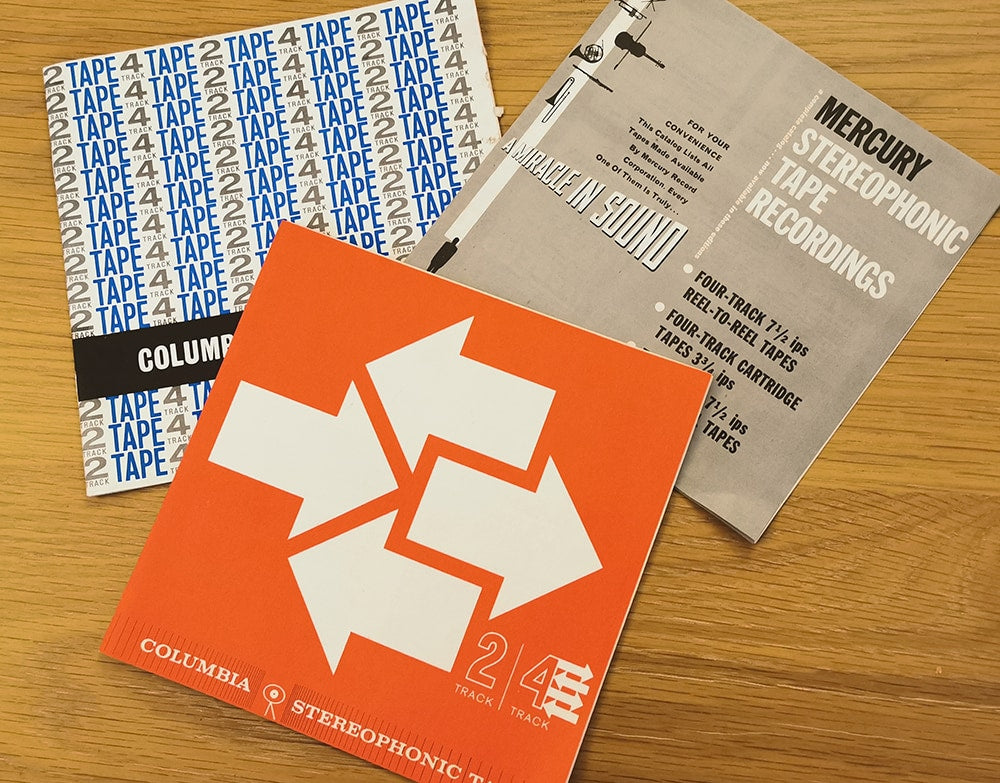

Header image: tape catalogs showing listings for both 2-track and 4-track versions of titles. All photos courtesy of the author.