In rock and roll you always take the wins where you find them. Al Staehely is the only person who has both played Carnegie Hall and provided legal services for Stevie Ray Vaughan. A musician with a law degree, he headed to California like so many others with a dream to make it big. He arrived in Los Angeles in 1971, and a few months later he and his brother John were asked to join the critically-acclaimed band, Spirit. With Al as the band’s new lead vocalist, bass player, and chief songwriter – and with brother John taking over lead guitar duties from Randy California – Spirit recorded their fifth album, Feedback, in November of 1971.

When Spirit later broke up, Al and John formed the Staehely Brothers, releasing the album Sta-Hay-Lee on Epic Records in 1973. It was an album that received good reviews, but the act was short-lived. When his brother John got an offer to join Elektra Records’ act Jo Jo Gunne – a band whose albums had consistently hit the charts – Al decided it was time to go it alone.

Having written most of the songs on both Feedback and Sta-Hay-Lee, Al began focusing on his writing, getting Bobbie Gentry, Marty Balin and Keith Moon among others to cover some of his songs.

But his focus was always on securing a solo record deal. Staehely recorded more than a dozen tracks in LA between 1974 and 1978, working with a collection of first-rate musicians that included Steve Cropper, Jim Horn, Gary Mallaber, Snuffy Walden, and Pete Sears. Between sessions, Staehely headlined clubs in L.A. and New York City, opened concerts for The Moody Blues and Hot Tuna, did sessions for Keith Moon’s solo LP, and toured with Chris Hillman.

In 1980, Staehely returned to Texas and decided to make law his focus. Between 1980 and 1985, in addition to the law practice, he did two tours of Europe, and an album, Monkey Medicine, with John Cipollina and Nick Gravenites (of Quicksilver Messenger Service). He also recorded a solo album, Staehely’s Comet, released in Europe on Polygram in 1983, as well as a yet-to-be-released album produced by Andy Johns. He didn’t totally focus on law until 1985. That led him to providing legal services to Stevie Ray Vaughan, who had been kicked off David Bowie’s Let’s Dance tour due to a dust up between managers.

This fall, Al will release solo recordings from his days in Los Angeles titled Post Spirit 1974 – 1978 Vol. 1. The initial track is “Wide Eyed and Innocent,” which is coupled with a new version of the song. We had an opportunity to speak with Al and discover some unique stories about his musical journey. From a legal perspective, we did get a point of view on perhaps the most important musical litigation of our day: Spirit versus Led Zeppelin.

Ray Chelstowski: What made you decide to tackle this project now?

Al Staehely: Well, it’s something I’ve wanted to do for a long time. I have had this high-quality stuff, and for a variety of reasons it was never released. But as for why now – it’s kind of the combination of getting the right team together, and kind of, where I am in my life. If not now, then when? I knew that I could just do a “digital dump” [and put the music out there]. But I thought that this material deserved a bit more than that. Ron Stone from Gold Mountain Entertainment (who managed me when I was with Spirit and then went on to manage everyone from Bonnie Raitt to Nirvana) and I reconnected in France a few years back. We kept in touch, and I helped him with a couple of things.

I called him when I was thinking about doing this, to find out if he knew of any digital marketing people who could help me do more than just put this out there. He put me in touch with an ex-Warner [Records] guy who has his own company and [who Ron] puts all his acts with. So, I reached out to him. We spoke a few times and I called Ron back to let him know that I was going to use his guy. He said, “you know I’m a manager, don’t you?” So, everything kind of came all together. I just didn’t want my son to one day come across these tapes in big plastic boxes and wonder what to do with them.

RC: Where were these recorded and what condition were the tapes in? Did you have to remix anything?

AS: Some of these recordings were done in legendary studios like The Record Plant, engineered and produced by guys who helped make some of the biggest records of the 1970s. I had everything [the tapes] baked and transferred to digital to keep them in the best shape possible. But nothing was remixed. These were [the] 2-track mixes from back then.

RC: Were there any tapes you looked for in those boxes that you had wished you had found but didn’t?

AS: Right toward the end of Spirit, we did a couple of shows with the James Gang and Cozy Powell on drums. If anyone possibly recorded one of those shows I would love to hear it!

RC: You assembled some remarkable musicians like Steve Cropper to back you on these recordings. How did that come about?

AS: I was renting a room from my friend Austin Godsey, who was an engineer and had worked on “Sweet Home Alabama,” and with Stevie Wonder and all sorts of people. He had also worked with Cropper before. They were good friends and I met Cropper through him. This batch of recordings came after years of trying to get a solo deal. I finally got one, signed the contract and started the record. Steve Cropper, Gary Mallaber (drums, Steve Miller Band, Eddie Money, others) and Pete Sears (bass, Starship, Rod Stewart, others) became the backup band.

I had known Sears from Starship. I was one of the three people they auditioned to take Marty Balin’s place when he left Starship in 1978. In fact, Marty suggested to the band that they hire me to take his place because he liked my songs. He had never liked the way the band democratically approached song selection, where everyone would get three songs [per album]. Marty always wanted to just pick the best one, like they did with “Miracles.” They auditioned three of us, one per week. The last to go was Mickey Thomas, and of course Mickey Thomas is such a great singer that he got the gig. The other thing he had going for him is that he didn’t write his own stuff (laughs). So, he didn’t present any competition to the other members when it came to getting songs on an album.

I do have a great story about Cropper though. We were recording at the house and Cropper had this little Fender Harvard tweed amp. It was in such good condition that I thought it was a reissue. So, I asked him if it was. He said, “oh no man. Everything you’ve ever heard me do on a record is through this amp.” I asked, “Everything?” He said, “Yep, everything.” We were recording in the fall and the Santa Ana winds were blowing in. In L.A., everything wasn’t air-conditioned, especially in the hills above Studio City. It was getting really warm, so we decided to knock off for a few days. Cropper leaned his guitar up against that amp and left. Over the next few days it sat there like a shrine, and I pointed it out to everyone who came by to visit: “see over there? Everything you’ve ever heard Steve Cropper do is through that.” Interestingly enough., about six months ago I saw an interview with Cropper, and he was talking about the equipment he uses. As it turns out that amp is now in the Smithsonian.

RC: Why didn’t this material get released before?

AS: [A&R man and producer] Greg Geller had given me $5,000 to do some demos. He offered to send them to his management team in New York and if they liked it, maybe we might be able to do a solo deal. A couple of days later he called and said, “hey do you know [producer] John Boylan?” I said I did, because he had managed Linda Ronstadt. He apparently wanted to work with me on my demos, so I asked if they could send over a couple of the things he had done, just so that I could get a feel for him. They sent over a test pressing for a group that hadn’t come out yet. I listened to it. It wasn’t the kind of stuff I was doing but it was real well done. Turns out it was a test pressing for the first Boston album, which I wish I still had!

Right out of the box the Boston record was a smash. Suddenly, Boylan was having to go out and meet the band on the road. This slowed my project down quite a bit. We finally got the demos ready to be sent to New York, to Steve Popovich, who was the head of A&R at Epic [Records]. Geller told me that Popovitch had heard the tape and liked it. But before the deal could get finalized Popovich left Epic to start Cleveland International [Records] with Meat Loaf.

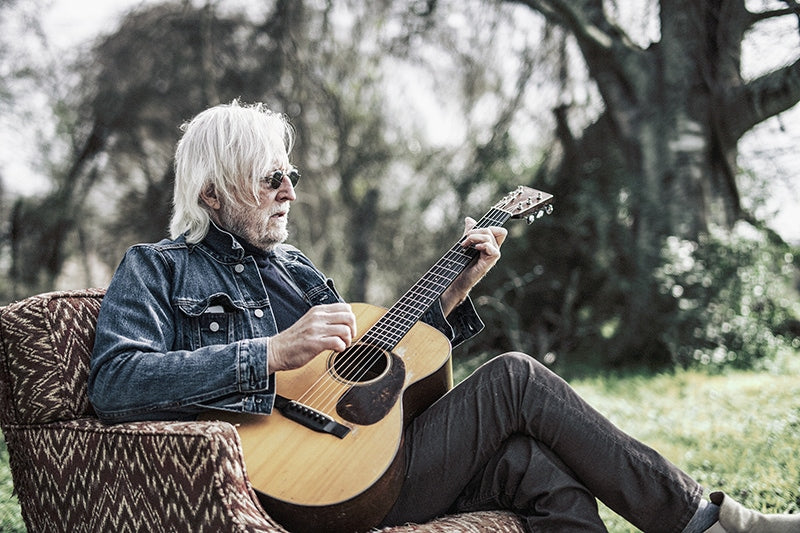

Al Staehely. Photo courtesy of Hill White.

RC: Was it difficult to follow Randy California (lead guitarist and vocalist of Spirit, who left the band in 1972)?

AS: When I first started rehearsing with them Randy was still in the band. But he was very erratic. He’d play great one night and the next he was a completely different guy. Some of the guys told me that during the making of [the album] Twelve Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus he had been thrown off a horse. He had hit his head and that may have had an effect. Whatever it was, before our first gig he decided to leave the band. Then [the other band members] John Locke and Ed Cassidy decided to keep working.

When the band broke up the partnership agreement stated that the [Spirit] name stayed with the remaining members. So, my brother and I ended up owning the name. We did one tour of Australia and a couple of shows without any original members. Then we probably made a mistake. Randy and Cass had decided that they wanted to start playing again, so we worked out a deal that gave them back the name Spirit. We weren’t comfortable using it if they were reuniting. That’s when I learned the value of a brand name. Even though [we had] the same lead singer and so on that fans had been hearing for the last couple of years, when we didn’t have the name Spirit any longer the booking agents couldn’t get us gigs – at least ones that would get us to break even. So, The Staehely Brothers never toured. In retrospect I should have just kept the name. The way these bands are, a year or so later a bunch of the guys probably would have started coming back to the group.

RC: After you left Spirit, I read that you saw Al Jarreau play the Troubadour and thought, “If this guy doesn’t have a record deal, what am I doing here?’”

AS: When I was with Spirit and we would headline Carnegie Hall I’d think, “isn’t this great! I’m never going to have to do anything but concerts from here on out. I’ll never be back in a club.” Well I was humbled pretty quickly with the loss of a brand name. I did a few of those Monday nights at the Troubadour where you got 15 minutes to do three or four songs, and one night I did catch Al Jarreau. After hearing him sing I thought just that!

RC: This all led you back to pursue a career in law. How did you come to represent Stevie Ray Vaughan when he had been thrown off the David Bowie Let’s Dance Tour?

AS: I got the gig with Stevie through Cutter Brandenburg, who was his main roadie. He put us together. Stevie already had management, but he didn’t have a lawyer. The one thing his PR people handled well was making this look like Stevie was the one who didn’t want to do the tour. But he really did want [to get] back on. I was in Sweden at the time, and I was supposed to meet up with him for the beginning of the Bowie tour. His first album was about to come out and we were going to talk about making some sub-publishing deals for him.

I called his house from Stockholm to find out where he was staying in Brussels. Lenny (Stevie’s then-wife) answered the phone. She told me he wasn’t in Brussels; that he was there with her, and that it was best if he explained why. Stevie told me that his manager Chesley Millikin and Bowie’s manager got into it at the rehearsals in New York. Chesley wanted Stevie and Double Trouble to be the opening act on [the Bowie] tour and for whatever reason Bowie’s people didn’t want that to happen. It blew the deal. Stevie said, “if I could get on with David think I could put it back together.” I found out where [David and his people] were staying and spoke to Bowie’s manager. He said, “look, I don’t ever want to talk to Chesley Millikin again.” I responded with, “well, what if I could work it where you never have to speak to Chesley again, you just speak to me?” He said, “if we had spoken a few days ago we could have worked this out. But I already have [session guitarist] Earl Slick on a plane to rehearse and I’m not going to tell him to go home at this point.“

RC: The Spirit estate engaged in one of the highest-profile legal battles in music when they took on Led Zeppelin over whether Led Zeppelin stole the opening riff to the Spirit song “Taurus” for the opening of “Stairway to Heaven.” Do you think Led Zeppelin stole from the song “Taurus”?

AS: I don’t know. I haven’t exactly been swamped with inquiries about it. I didn’t follow the case that closely. I did talk to Randy California’s sister because I was hopeful that [the people representing Spirit] would be successful. Certainly, Led Zeppelin had a history of this kind of thing, and they certainly didn’t need the money. She told me that if they had been successful, all the money was going to go to a non-profit that Randy had put together to help buy instruments for young musicians. It’s too bad. I think they had a credible case.

Header image of Al Staehely courtesy of Hill White.