In the fourth quarter of 2021, the Audio Engineering Society (AES) held its annual fall show online in October, because of the pandemic still being in effect. The show seminars and interviews were recorded for on-demand viewing, so once again (as was the case in 2020), attendees and reporters could still participate virtually. Part Two of this series (Issue 152) included a look at keynote speaker and Grammy award-winning producer Peter Asher, coverage of a seminar on stereo panning and balancing in recording, and a workshop on controlling low frequencies when tuning a listening environment. Part One (Issue 151) featured a symposium with electronic instrument designers of the Prophet-5 and Oberheim OBX-1a synthesizers, and a discussion about PA system optimization in recording studios and venues..

Platinum Producers (St. Vincent Interview)

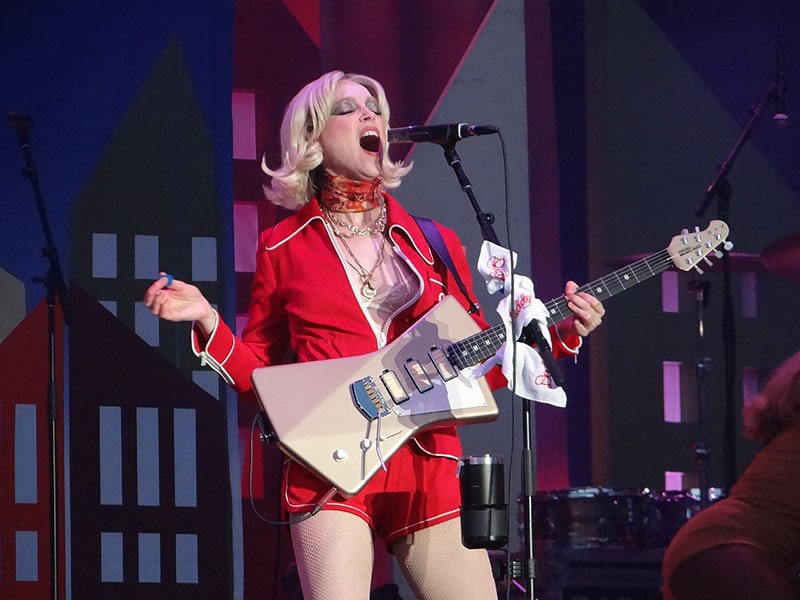

Under the stage name of St. Vincent (taken from a Nick Cave song), Annie Clark has become a critically acclaimed singer, songwriter, producer and guitarist, and has garnered multiple Grammy awards for her art-rock albums and her unique and stylized approach to creating sounds. Similarly, she is the only female rock guitarist with a signature guitar model, which she designed from the ground up without having it based on a pre-existing template. She has also written screenplays and acted in films.

Although best known for his Grammy award-winning work in country music with artists like Glen Campbell, Jennifer Nettles, and Eric Church, Julian Raymond is also an A&R executive for Big Machine Recordsand has worked with Cheap Trick, Fleetwood Mac, Kottonmouth Kings, and others.

Raymond interviewed Clark about a variety of music production and other topics that provided some of the perspectives and ideas that permeate her recordings. Witty, humorous and articulate, she was impressively candid and self-reflecting.

The interview started with Clark’s work on the film The Nowhere Inn, a faux documentary written by and starring St. Vincent and Carrie Brownstein of Sleater-Kinney. Clark amusingly recalled her “rookie move” of foolishly composing the score before the editing for the film was completed, resulting in her “chasing her tail” for months, trying to rewrite and modify all of the music to fit the on-screen images.

Born and bred in Tulsa (home of Wanda Jackson and J.J. Cale) and later Dallas, Clark notes that the Dallas music scene of her teens had some freakish music acts that influenced her tastes, artists like Gibby Haynes and The Butthole Surfers and The 13th Floor Elevators. She attributed this to an outgrowth of religiosity, a reaction to social norms, and a lot of acid.

Julian Raymond and St. Vincent. Courtesy of AES.

Julian Raymond and St. Vincent. Courtesy of AES.Another local band that she cited was Tripping Daisies, some of whose members she played with in the Dallas music scene after starting her first gigs at age 15.

Annie Clark noted she was grateful that she was born during a time when music was still very much guitar-driven, which allowed her to gravitate towards the guitar as her primary instrument. If she had come from a different era, she saw herself possibly based more around an Akai MPC (sampler and sequencer) or a laptop, which would have changed her entire approach towards creating music.

She recalled her stint at the Berklee School of Music as fascinating because of her exposure to jazz music theory, where dissecting a Charles Mingus composition contained lessons that never materialized in her own works until her recent Daddy’s Home album, which has, in her words, “chords with lots of numbers, y’know.” Her summation of music school was that “it gives one the tools and skills to become an artist, but cannot teach someone how to be an artist.” She jokingly likened Berklee to “a very, very expensive trade school.”

Joining The Polyphonic Spree as their guitarist gave Clark her first taste of touring, including opening for her idols, Sonic Youth.

Having been a longtime fan, Julian Redmond went into detail in asking about St. Vincent’s record catalog and his favorite song from each album.

He cited her debut, Marry Me (2007) and in particular the song, “Your Lips Are Red” as one of those records that are just so good that it made him consider quitting the music business. Clark replied that “Your Lips Are Red” was actually a murder ballad, and that the Marry Me record, in retrospect, is probably the most successful musical fusion of her influences at a given point in time – in this case, Nick Cave, and Stravinsky-type strings, and also gave a shout out about keyboardist Mike Garson’s playing on the record and his ability to go “from Debussy to outer space and back again.”

She likened looking back at her catalog to viewing one’s high school yearbook photos. During college, they might seem embarrassing, but over the course of more years, a greater appreciation for that moment in time can settle in, and in fact, some songs from Marry Me are being considered for being played again in upcoming performances.

She related her bare-bones recording setup for the album as consisting of an Audio-Technica mic purchased from from Guitar Center, an Avid M-Box USB interface (into which she plugged her guitar directly, as she could not afford an external guitar preamp at the time), and a computer – with the majority of it recorded in her childhood bedroom. Clark laughingly noted the exceptions were her neophyte attempts to record her family piano in the living room with the mic inadvertently overloading, and her trips to Birmingham, Alabama, where the drummer from the Polyphonic Spree lived, and she was able to record drums and overdubs there. An engineering friend, Daniel Farris, helped. Exposure to some of David Bowie’s late 1970s and 1980s records, like Scary Monsters, would become hugely influential Marry Me and later works.

St. Vincent. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Justin Higuchi.

St. Vincent. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Justin Higuchi.

Comparing it to a “1940s film score,” Redmond gushed over how impressed he was with the song and production of “Just The Same, But Brand New” from the Actor album. Clark wrote the song at the home of her uncle, Tuck Andress (guitarist extraordinaire of jazz vocal duo Tuck and Patti), thought it would be the perfect ending for the album, and admittedly ruined that idea by adding an extra last song on a spur-of-the-moment decision.

Recorded on analog tape with Scott Solter in rural North Carolina, Clark recounted Solter’s increasing mental instability and her feeling of being trapped in the middle of nowhere with him, scheming more about how to get the tapes smuggled out than about her own safety. Without going into detail, she summed up the experience: “Maybe don’t introduce polyamory on the day we start a record with your engineer and your wife –maybe do that on your record, but not on mine!” Returning back to Texas with her tapes, the songs were in various stages of completion, along with lots of brass and string parts, and she finished the songs around these ideas and sketches with producer John Congleton.

Raymond considers “Cheerleader” from Strange Mercy to be the best alt-rock song of all time. He pointed out a distinct Beatles vibe, which Clark acknowledged, and that the record was written during an emotionally difficult period for her in New York. With some of the songs completed, she went to Seattle, rented out Jason McGerr’s (Death Cab For Cutie drummer) studio and worked in isolation for weeks, later finishing the album in Texas with Congleton.

Love This Giant, her collaboration with David Byrne, had its genesis when she met the former Talking Heads leader at a charity event (which featured original music from Björk, and The Dirty Projectors.) Asked by the promoter to collaborate on some music for the charity, she and Byrne started and then kept going until they had an album’s worth of new material. Although they were both in New York City, they worked remotely, e-mailing files to each other and then contributing new parts. She remembered the experience fondly and exclaimed that she learned a lot about showmanship and playing live with a horn section from her subsequent tour with Byrne.

“I Prefer Your Love” from the St. Vincent album is a personal song written for her mother. after a bout of insomnia and the subsequent news of her mother’s heart attack,. St. Vincent was her first Grammy award win (for Best Alternative Music Album). She also felt that during the making of that record, it signaled the turning point where she fully embraced the persona of St. Vincent as a separate entity from herself and as an extension of her musical work.

Raymond stated that the song “New York” from the album Masseduction redefined and replaced Lou Reed’s “Walk On the Wild Side” for him as his personal iconic New York song. St. Vincent joked that although she won another Grammy that year for “Masseducation,” she imploded her commercial radio prospects with her insertion of true-to-life profanity into the lyrics of “New York.”

Proclaiming the Daddy’s Home record as “an artistic pinnacle,” Raymond name-checked all of the New York, Lou Reed, Andy Warhol, 1960s and 1970s sonic ideas, psychedelic Pink Floyd, and Berlin-era Bowie elements that crop up in the album, citing “Live In The Dream” and “The Laughing Man” as standout tracks.

The humming interludes on the record, Clark said, were portions of a single song, chopped up into small chunks akin to “a palate cleanser” or a “Texas breeze” in between the heavier New York-minded songs. The song was originally conceived as a tribute to her mother’s and sisters’ stoicism and inner strength during her father’s incarceration for financial fraud. She joked that her obsession with Pro Tools in getting the interludes timed down to the millisecond was a result of being quarantined during the pandemic.

“Live In The Dream” was, in Clark’s words, “a tip of the hat 120 percent to Pink Floyd,” with a dose of gritty downtown New York circa 1970 – 1976 mixed in, along with influences from records from that period by Steely Dan and Stevie Wonder. Unlike the structured musical approach and accusatory lyrics of her past records, Clark created Daddy’s Home as a more groove-oriented series of stories about people struggling to get by.

“…At the Holiday Party” (from Daddy’s Home), a song where she worked with producer Jack Antonoff for the first time, was a result of Clark “finally getting the Stones” and songs like “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” with themes of “trying to hide sadness through [the acquisition of] material goods, and how we often reveal ourselves though the things we are trying hardest to hide.”

She was effusive in her praise for Antonoff, who also contributed drums, bass, Wurlitzer electric piano and clavinet, and had a sympathetic musical telepathy with her in translating ideas immediately into musical parts over a scant five days of working together at Electric Lady Studios in New York.

At the conclusion of the interview, Clark and Redmond shared film-scoring war stories, where in Redmond’s case, he had a bitter fight with a producer over a song he had written, and the director backed Redmond up. The song subsequently got an Oscar nomination. Clark had had a similar problem, resulting in her asking, “Why did you hire me if you want an acoustic guitar?”

They also discussed her signature Ernie Ball Music Man guitar, which she created from scratch (see photo above). The angular shape was inspired by performance artist Klaus Nomi, and Clark personally came up with the various electronics configurations and paint job options.

Archival Albums: Curation, Preservation, and Mastering

As an integral part of our cultural heritage, the upkeep and preservation of historic recordings for future generations is crucial.

Moderated by Peerless Mastering’s Chief Engineer, Maria Rice, Archival Albums: Curation, Preservation, and Mastering featured comments from her colleague at Peerless, Jeff Lipton, as well as from Grammy award winner and Country Music Hall of Fame preservation engineer Alan Stoker, and mastering and preservation engineer Anna Frick of Airshow Mastering.

All of the panelists got their start in audio working on analog tape, an experience that definitely influences and informs their mastering and curating work. Stoker was manager of Nashville’s RCA Studios in the 1980s, and handled their first preservation transfers from the original radio station acetate discs and analog tapes when RCA built its first archiving lab during that era.

Anna Frick, Jeff Lipton, Alan Stoker and Maria Rice. Courtesy of AES.

Anna Frick, Jeff Lipton, Alan Stoker and Maria Rice. Courtesy of AES.In the early days, Stoker recalled transfers would be flat (with RIAA curve defeated), acetates done from right off the turntable, recorded at 15 ips in mono. One trick was to use a stereo cartridge in conjunction with a transient noise suppressor. With this setup, the output from the stereo cartridge would continually be switched to the quieter side, enabling the cleanest possible transfer to tape. Some of the archival recordings Stoker used this process on include:

- 1939 – First-ever Grand Ole Opry recording (now part of the Library of Congress archives)

- Elvis Presley’s first recording (from a 1954 acetate demo recorded for Elvis’ mother)

- The first-ever recordings by Roy Orbison and Jerry Lee Lewis

Stoker played a video about the 2015 digital transfer he performed on the Elvis acetate after it was acquired by Jack White.

Screen shot of video featuring the original acetate recorded by Elvis Presley at Sun Studios. Courtesy of AES.

After White handed the surprisingly good-condition disc over to Stoker:

- It was cleaned with distilled water.

- He then carefully listened for surface noise or any disc imperfections that might cause the stylus to track inaccurately, using both elliptical and conical styli to play back the record at various groove depths. To cleanly transfer a disc, Stoker will usually attempt to have the stylus ride above the sections where embedded wear cause noise.

Jack White with Alan Stoker. Photo courtesy of AES.

Jack White with Alan Stoker. Photo courtesy of AES.Stoker noted that he had performed a digital transfer on that same acetate for the previous owner back in the 1980s, which appeared on an RCA Elvis Presley CD box sets.

He also mentioned that most of the archival and curation work he handles is due to the acquisitions program of the Country Music Hall of Fame Museum, which has over 250,000 discs and 35,000 78 rpm records. They come from radio stations, personal collections, and owners from across the country. There is also an active program for the digitization of the Country Music Hall of Fame’s enormous analog tape library, which includes thousands of radio show broadcasts and other historic music recordings. Much of the library’s video and audio content is accessible in person via appointment, and digital streaming of selected material is available online.

At Airshow Mastering in Colorado, Frick noted that their studio receives a substantial amount of institutional recordings for digitization, which also require extensive cross-referencing information for cataloguing purposes. She uses FileMaker to create a customized data record for each client from her templates.

The sound sources range from records to Sony digital 1630 tapes, to a great deal of analog cassettes (much of it consisting of live Grateful Dead performances). When not constrained by budgets, they are able to apply the Plangent Processes system during transfers, which uses software and tracking of tape recorder bias frequencies to reduce wow and flutter from the source material tapes and also reduce sonic artifacts and unwanted noises.

Frick recalled her first exposure to the Plangent process with an A/B comparison of a processed recording versus a flat transfer of a Doc Watson master. She said that the differences were startling, and that the improved audio quality resulting from the Plangent process made her much more keenly aware of the brilliance of Watson’s guitar playing, which had been recorded decades before she was born.

Lipton, also a data specialist, started Peerless Mastering in his Massachusetts bedroom in 1994, and the work that came in as a result of positive word-of-mouth referrals allowed for the business to grow to the point where Peerless was able to design and build separate acoustically accurate rooms for their mastering jobs. The paneled walls of Room B (where Maria Rice was moderating from) reflect the sound up to the ceiling, where there is a 5-foot layer of acoustic treatment to deaden the room from any reverberation. From Lipton’s location, Room A was designed to be an acoustically flat environment from 10 Hz to 35 kHz, and is used for 5.1 mastering (with a 7.1 upgrade scheduled for 2022).

In making distinctions between the various subcategories of audio archiving, Stoker indicated that most of the work he does is preservation, i.e., creating a pristine version for safekeeping, with high-quality copies to enable succeeding generations of listeners to hear them with optimum clarity.

Restoration involves the use of notch and peak filters and parametric EQ to bring out the best sonic qualities of a recording before printing the best-possible version. Clicks or pops from analog tape have to be physically cut out with a razor. Stoker laughingly noted that the first time he saw a waveform on a screen and could use a stylus on a computer program to remove ticks and pops from audio, “it blew my mind – it was like a dream come true.”

All digitization for the Country Music Hall of Fame library is conducted at 96 kHz/48-bit resolution into Cubase, with 48/24 derivative files and access files at 44.1 kHz CD-quality. The preservation files are never touched again.

Frick said she normally works at 96 kHz/24-bit but is currently on a special project that requested 128 kHz resolution. A good deal of her work involves client education, including teaching the clients how to back up files, why the preservation master should never be touched once it is created, how to work off derivative files, and other considerations.

As the bulk of Peerless’ mastering work is for commercial release, Lipton explained how they always keep an extra copy of an initial flat transfer of every project before it undergoes any processing, depending on the client’s requirements. Lipton deploys multiple servers for automatic redundancies and backup in all data-handling functions, in addition to additional cloud servers, hard drive and even CD-R backups.

A key benefit of their intensive record-keeping of files attached to every project at Peerless is the ability to recall any of them over the last two to three decades, and to have all of the pertinent information about that project instantly available.

Since restoration projects often come in with DAT tapes as source material, older digital technology is known to have a certain sonic “coldness” due to the limited harmonic content of the recordings as the result of using older A-to-D converters. In these cases, Peerless will use certain techniques to “warm them up.” This could involve the use of analog tube EQ or compression, or even printing to analog tape, to avoid the sterility of older direct-to digital recording and mixing. Since he started in the 1990s, Lipton seemed relieved to have avoided the razor blade experiences of analog veterans like Stoker, and he prefers to use the CEDAR noise reduction system for removing pops and clicks on source material.

On the topic of over-enhancement and perhaps overly tampering with the sonic character of the original source material, Frick noted that on spoken-word projects, intelligibility has the greatest priority, even if the voice may get momentarily altered unnaturally in achieving that goal. With music, preservation of a performance is crucial, but the area is considerably more gray as to where to draw the line.

Stoker makes his critical judgments based upon his decades of intensive listening to live music, and opts for keeping the sound of live music as his guideline, so any unnatural sounds to instruments with which he is familiar will alert him to potential heavy-handedness with his sonic processing. He noted that it’s too easy to overdo things with digital, so he advised stepping away to listen with fresh ears the next day to reassess and undo, if needed. Stoker has even chosen to leave background noise in when its removal kept the music from sounding “alive.”

Rice spoke of compilation project challenges where source material can come from a range of different formats. Lipton said the goal was to perform changes to the material as minimally as possible to preserve the original music’s integrity, maintain a uniformity of audio clarity and eliminate distracting noise and other artifacts, while avoiding sterility.

On the topic of preserving recordings that are integral to the preservation of cultural history (versus simply doing reissues of commercially popular music), Frick cited a project she worked on involving the musical oral history of the Navajo tribe. It included field recordings and some religious and ceremonial chants and prayers that would otherwise have become lost to the current generation. The project also preserved vocabulary and other parts of the language that have since fallen into colloquial disuse.

Stoker cited his work on 1930s radio broadcasts as archiving all-important aspects of American history, since radio has undergone so many changes over the past century. He noted that leading up to and through the World War II era, radio would have separate programs and time slots for children, housewives, blue collar workers, and other targeted listening demographics.

In summary, among the current and future challenges of archiving, all the participants acknowledged the fact that everything that’s newly-recorded is predominantly already in digital format and is now designed for streaming. As a result, the sound itself requires limited to no processing, but data management, creating metadata reference information for cataloging and library purposes, and creating links for other databases of all are becoming more ubiquitous. The ease of digital recording makes organizing the current increased volume of files a daunting task.

Citing how digital filenames get truncated when using an iPhone or other device, and how transfer of files to multiple devices can often obscure their identification, Frick ruefully noted, “I don’t envy the next generation who will have to wade through all of these [altered] filenames.”

Header image: St. Vincent, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Thomson200.