I was talking with singer/songwriter Ryan Hamilton the other day about his thoughts on the music of the 1970s and early 1980s. A celebrated musician within the world of Americana, Hamilton has just followed up last year’s award-winning release, This Is the Sound, with his latest album, Nowhere to Go but Everywhere.

Ryan and I talked about his early influences. He admitted that the music his Dad loved from that era continues to inspire him to this day, because what musicians were making sounded so new, and there was something really “free” about their creative process. When he mentioned that Bob Seger was one of his influences from that period I relayed a story I thought Hamilton would appreciate, especially because he is on Steve Van Zandt’s Wicked Cool label and Steve is Bruce Springsteen’s consigliere…

Whenever I am in Los Angeles I prefer to stay at the Sunset Marquis hotel in West Hollywood. It has a rich history rooted in rock and roll. Nestled below the Sunset Strip at 1200 Alta Loma Road, it’s located within a neighborhood and would go completely unnoticed if you didn’t know it was there. The hotel is set up in an oval around a large patio and pool and includes a sprinkling of private bungalows that dot the property’s perimeter. But the standout feature of any stay here is their bar. Named Bar 1200, it’s a small, quiet, dark room that is rarely filled with patrons but overflows with stories that almost never leave its walls.

There I have found myself alone on many a weekday night after a full day of meetings and kept company with only the bartender and a random guest like, oh I don’t know, Julian Lennon. Stars pop in and out of the Marquis bar quietly but sitting there ringside I have had many conversations with boldfaced names, talking about a range of topics as wide as music, guitars, watches, and tequila. The stories I hold most dear are those that involve the respect musicians have for other musicians and the collaborative spirit that once was the industry norm, not the exception. Because of this, a picture of the bar sits framed in my house and remains a steady reminder of some really terrific nights. As a famous and anonymous person once said of Bar 1200: “Don’t make it too popular or I’ll stop coming back!” Well said indeed.

My favorite story about Bar 1200 was one that I didn’t actually hear at the hotel. Instead I heard it thousands of miles away at the midtown Manhattan offices of Rolling Stone. I was there one day a few years ago while having lunch with Bob Seger, Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner and some members of the editorial team, we spoke to Bob about heading back out on the road behind what would become his second-to-last studio record. That night Seger was performing at Madison Square Garden and to most of us it was a surprise to hear that he still would get the jitters on stage. As a result he always tried to open with up-tempo tracks like “Hollywood Nights” to shake off his nerves. After all of those years of performing live and being known for delivering white-hot concerts it was stunning to learn that even “Boppin Bob” gets butterflies in front of an audience.

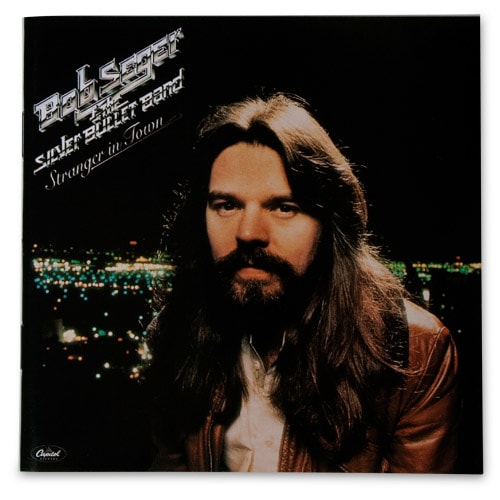

But the story that stopped me in my tracks was one he told about the Sunset Marquis. The year was 1980 and Bob was recording his masterpiece, Against the Wind.

This year a 40th anniversary edition of the record was remastered, but the packaging remained the same as the original release. There was no bonus material in the 40th anniversary release other than a 45-RPM single and B-side that came in a deluxe colored-vinyl version. So there was no forum like added liner notes or a booklet or anything like that in which to tell this fantastic tale.

It turns out that Bob was staying at the Sunset Marquis during the Against the Wind sessions. It also turns out that Bruce Springsteen was in town at that time mixing The River. As fate would have it, Bruce had decided to stay at the Sunset Marquis as well.

Bob Seger told us that he and Bruce Springsteen by this point had become close friends. In fact, Seger had been wrestling with the song “Night Moves” for a long time, not quite finding a way to knit what he had written together in a manner that wasn’t clunky or forced. According to Seger, it was Bruce who told him that it was OK to add more than one bridge to a song. As Bob told it, Bruce kind of “gave permission” to do what Seger had considered unorthodox. Seger made the change and the rest is history. Not only did Bob say that we would never otherwise have heard “Night Moves,” but even if we did it would not have become the hit that it did without Bruce’s important contribution.

The story then moves back to the hotel. Apparently during their time at the Sunset Marquis, Bruce and Bob would huddle at the bar every night and have dinner together. There they would run through their recording studio developments of that day. Bob would offer Bruce his thoughts on mixing, but in return, Bruce would give his track-by track-input for Against the Wind. Bob began to rattle off, track by track, the suggestions that Springsteen had made. Each dinner engagement was a working session that went into the night. None of us had ever had any idea that Springsteen had such an influence on Seger – and vice versa.

The following mornings they would stand outside the hotel, each waiting for their car to take them back to the studio. There Springsteen would use the moment to run through the changes they had discussed the night before, one last time. This went on for something like two weeks, where Seger at one point described the two of them to be something like an old married couple, making suggestions at Bar 1200 as to what the other should order for dinner based upon how they had “reacted” to the dishes they’d had the night or two prior. That time they spent they further deepened their now life-long bond and, let’s face it, resulted in two fantastic records that will outlive us all in relevance and relatability.

For a lot of performers, getting this much direction from a peer might have been hard on the ego if not simply difficult to process. But Bob Seger is arguably one of the most humble folks you might ever meet. He rarely takes credit for any of his success, instead feeling more comfortable passing that along to others.

Later in the lunch he told us about the time he walked through a diner in his native Detroit with his family after finishing breakfast. It was an early Saturday morning and as he passed through the booths, an unemployed auto worker who Bob had nodded “hello” to responded by asking Bob why he hadn’t done anything to help the ‘Big Three” automakers (General Motors, Chrysler and Ford) bounce back from the recession the industry had fallen into. Bob stopped and spoke with the auto worker and his friends, leaving the diner determined to do something.

Through his team, he made his song “Like A Rock” available to Campbell Ewald, Chevrolet’s then-advertising agency of record. The song was the title track of his just-released 1986 album and really was about how your late teens are the best years of your life. But Campbell Ewald cast the song as being about toughness, and kept it as the Chevy truck theme song for 12 years. During that time the company sold millions of trucks, and when they retired the song from being used in commercials, Chevy truck sales took a downward slide. The impact “Like A Rock” made on Chevy truck sales ties right back to that auto worker who stopped him at a diner to say his piece. That’s who Bob Seger is.

And that’s who people like Ryan Hamilton and I admire so greatly. They made music we will carry with us through our lives and hopefully pass on to our kids, and then they’ll pass the music on to their kids. But such artists are also creators of great character who live their lives with purpose, putting others ahead of themselves and also placing the highest value on the friendships they have forged. At the Sunset Marquis in 1980, the friendship between Bob Seger and Bruce Springsteen birthed some great music, and a story that always makes me smile.