“Great recovery Roy,” yelled the wrangler as I tightly pulled back on the reins of my horse whose front legs had collapsed on the steep downward slope.

This happened on the last day of our two-week vacation at a dude ranch near Buena Vista, Colorado.

After a trip to Cairo, Egypt and a ride around the pyramids on a very placid horse, I fancied myself a rider and with my wife’s approval we booked a trip to a dude ranch. The brochure boasted a western experience with riding every day.

The ranch was rustic but very comfortable, with one caveat – it was 8,000 feet up a mountain.

Situated near an abandoned silver mine in the middle of a national forest, we reached it after a 10-mile drive on a dirt road. At the time we visited in 1991, the ranch had no direct telephone line, only an emergency communication system. They had also just been given an official street address so they could receive parcels via UPS. This was good because I sent a case of wine before our arrival.

The accommodation was very comfortable but we were on the second floor and as I was not acclimated to the elevation, it was one staircase too much. Wheezing and panting, I struggled up the 15 steps to collapse on my bed.

That evening after a copious dinner of meat and potatoes, (every night there were delicious versions of that theme) we had orientation. This started out as silly games and jokes to relax everyone. Then came the long list of safety rules and the schedule for the next few days. Weary from the travel and the altitude, I forced my way up the never-ending staircase to my bed.

“Riding every day.” This turned out to be a curse as I wasn’t to the saddle born. The first day, we were assigned horses according to individual skill and experience. Mine was a placid stallion that seemed to be gentle. We were taught how to push away from aspen trees because the horses loved to unseat their riders by scraping along the side of them. Forewarned and very nervous I saddled up and we took off up the mountain.

At first the trail was easy but at one point we trotted onto the edge of a cliff. The drop must have been thousands of feet. I then realized that my life depended on the sure-footedness of a 1,000 lb. nag. I tensed up, shut my eyes and hoped to survive. Apparently, I didn’t die as we started slowly to descend. The whole ride took an hour or so and after we returned, I found upon dismounting that my legs were frozen in the same position as they were on the horse. For 45 minutes I couldn’t straighten my legs, then slowly I managed to crawl on all fours to my room.

Every day we rode, and slowly, while I learned how to control my horse, my breathing started to ease. One morning we all rose early and rode up the mountain. When we arrived at a clearing, the biggest frying pan I had ever seen was already on a fire cooking bacon and eggs. That delicious breakfast, eaten in the pure mountain air while gazing at the Rockies, framed by aspen trees, was magical.

With my western boots, Wrangler jeans and Stetson, I was turning into a facsimile of a cowboy.

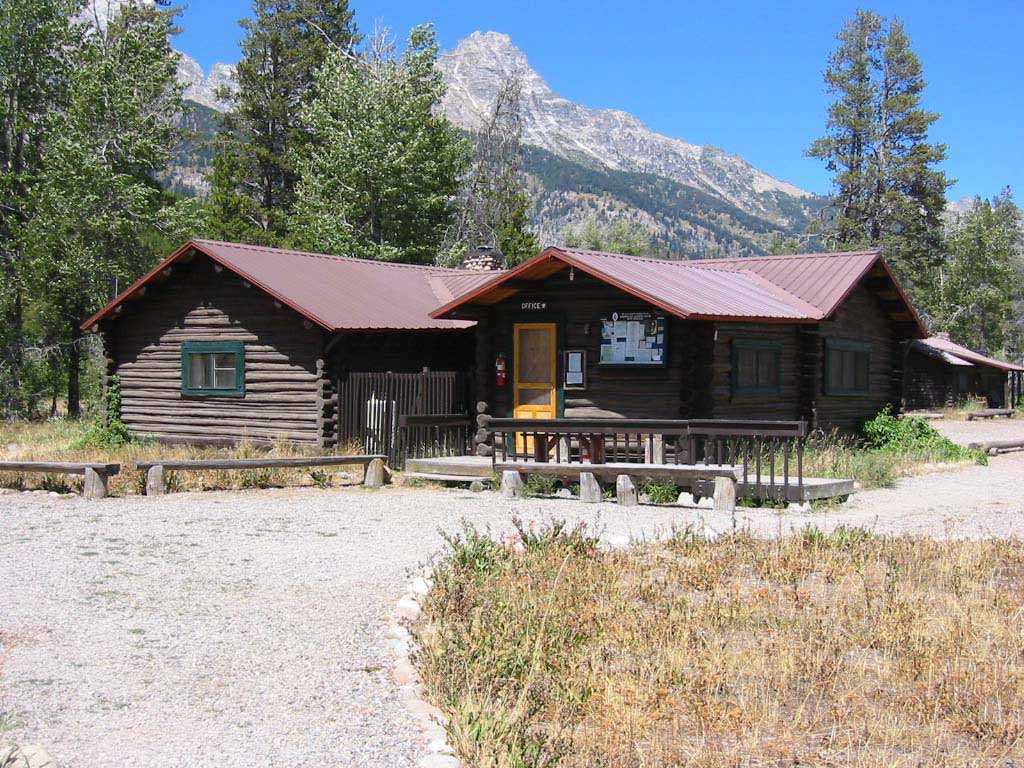

Eaton's Dude Ranch, Wolf, Wyoming. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress/Carol M. Highsmith.

Eaton's Dude Ranch, Wolf, Wyoming. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress/Carol M. Highsmith.

Some days, when we chose not to ride, were fun. We went white water rafting in the Arkansas river, which was exciting and a little dangerous. A road trip to Aspen via the 12,000-foot-high Independence Pass was hair-raising as one of our wranglers drove a van at high speed on this two-lane road with sheer drops, no barriers and hairpin bends. We briefly stopped at the summit and if 8,000 feet makes you short of breath, don’t go higher. Aspen was lovely if a little twee.

Back at the ranch, I tried my hand at skeet shooting, mostly missing the target and discovering that my eyes weren’t as good as they used to be.

Fishing was abundant as the ranch had a pond that was well stocked with trout. But even better were the pools built by beavers. Sometimes (I guess before their lunch) these pools were also well-stocked. One day my son Ilan caught a large trout. To put it out of its misery I, as my father had taught me, grabbed it by the tail and smashed its head against a rock. Nine-year-old Ilan was mortified by this and refused to eat it that night when it was served whole roasted on a plate.

Meals were “good and plenty.” The wranglers ate with us. They were a great crew, typically young, from all over the West. Most of them had been riding since childhood and they really kept an eye on us on the trail. For the guests, dinner was a time to schmooze and relax. Not so for the wranglers. They shoveled the food into their mouths and hurriedly left. Maybe they had chores to do or as I suspected, the less time they had to spend with us, the better.

The ranch had a pig who ate the leftovers from the diners every night. From time to time, the ranch would buy a young pig, fatten him up, then butcher him. The owner told us that the pig always got agitated when she approached with the leftovers, but what really freaked the owner out were the times when the leftovers were pork. This caused the pig to grunt gleefully with anticipation before devouring his cousins.

On the first day of our second week, a new group of guests arrived. The following day a man in his fifties sat opposite me for breakfast. He was resplendent in his brand-new, squeaky-clean, Orvis Outfitters, fly-fishing gear. Without knowing him, I said, “You look like you should be wearing a suit.”

He glowered at me, stood up and moved to another table. Later on, I discovered that he was a Wall Street banker.

As I mentioned earlier, orientation on the first night consisted of silly games and so on. On the beginning of the second week, the owners suggested that I shouldn’t attend as it would be boring for me. Nevertheless, I went.

To break the ice, the owner asked the group a question, “What was your most embarrassing moment?” As he spoke, he turned, looked at me and said, “Roy?”

My answer?

“This is my second week.”

Header image of the Double Diamond Dude Ranch courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/National Park Service.