In my previous article (Issue 162), I discussed the early monophonic recordings of the violinist Nathan Milstein. He was a very popular artist in his day, and his recordings are easy to find and hence inexpensive. These microgroove monophonic LPs have a wonderful tone and they sound extremely life-like, even more so than many of the stereo LPs that followed. This time, I will discuss another violinist who had only made monophonic recordings, although she lived well into the stereo era.

Johanna Martzy was a Jewish-Hungarian violinist born in 1924 in Timisoara, Transylvania, then part of Hungary and now Romania. She received training from the famous violinist and pedagogue Jenö Hubay, a pupil of the great Joseph Joachim. She entered the Budapest Academy of Music at the age of 10, and made her public debut at 13. She graduated in 1942 and got married, but when Nazi Germany occupied Hungary in 1944, the couple was sent to a concentration camp. After the end of the War, Martzy resumed her performing career and formed a partnership with the pianist Jean Antonietti. She won first prize at the Geneva violin competition in 1947 and her career took off.

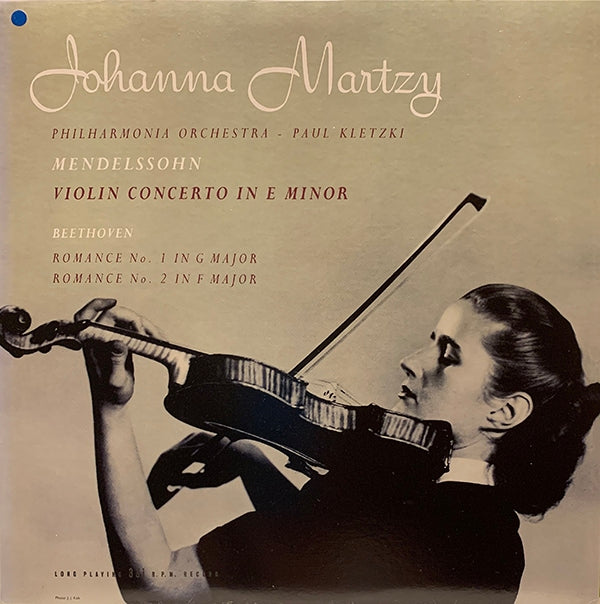

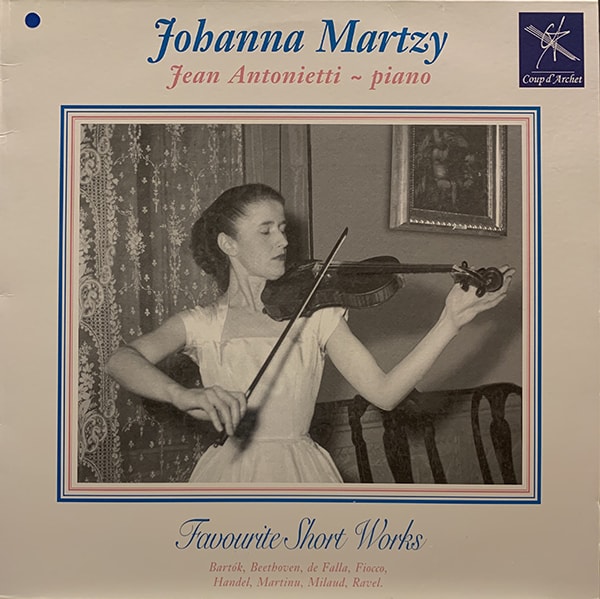

Johanna Martzy, Favourite Short Works LP.

During the 1950s, she had a busy concert schedule and also made recordings for Deutsche Grammophon (DGG) and EMI/Columbia. Notable recordings for DGG include an LP of Beethoven and Mozart violin sonatas; the Dvorak violin concerto with Ferenc Fricsay; the Mozart violin concerto No. 4 with Eugen Jochum; and an LP of short pieces for violin and piano. For Columbia, she recorded all of Bach’s Partitas and Sonatas for solo violin; the Beethoven, Brahms and Mendelssohn violin concertos with Paul Kletzki; and all of Schubert’s compositions for violin and piano. She also recorded the Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 and the Mendelssohn concerto with Wolfgang Sawallisch, but their collaboration was not a happy one and she ultimately refused to release the recordings during her lifetime.

Martzy, Dvorak Konzert für Violine und Orchester, DGG LP.

Martzy probably had quite a formidable personality, as she had clashed with various conductors throughout her career. A falling out with Walter Legge, the powerful record producer at Columbia, concert promoter, founder of the Philharmonia Orchestra and husband of Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, led to the termination of her contract with Columbia and probably precipitated the decline of her career. After her contract was terminated, all of her Columbia recordings were promptly removed from the catalogue, thus ensuring their rarity. Martzy never made a commercial recording again after 1958, but she continued to play some concerts until the 1970s. She died of cancer in 1979 at the age of 54.

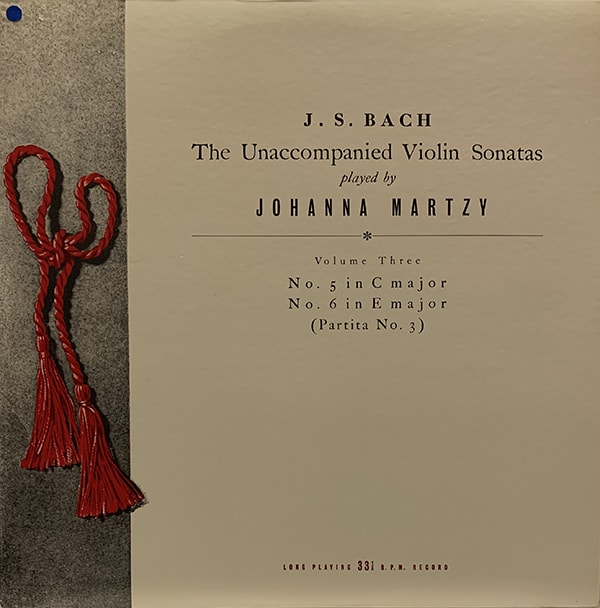

Martzy can be considered one of the first “modern” violinists. She had a formidable technique and played with precision and without sentimentality. At the time, some critics called her playing “austere.” She had great strength and her bowing was powerful, some would say masculine. By modern standards, she might be accused of using too much vibrato in her Bach. In her recording of Bach’s Partitas and Sonatas for Solo Violin, her playing is incisive and rhythmic, with a swift tempo, and devoid of the self-indulgences exhibited by some of her contemporaries. Her playing cannot be described as austere, as she played with passion and intensity, always in firm control of the ebb and flow of the complex interplay between the lines of polyphony. For some Bach lovers, her interpretation of the Partitas and Sonatas is unsurpassed. This has led to the original Columbia 33CX Series LPs becoming some of the most expensive classical records on the market, with a set of three in good condition selling for at least $5,000.

Martzy, J.S. Bach, The Unaccompanied Violin Sonatas, Volume Three, LP.

The Japanese were the first to rediscover this forgotten artist. Lexington, an independent record company in Tokyo, reissued the Bach LPs in 1995, and eventually all of her other EMI recordings as well as several Deutsche Grammophon LPs. Prior to that, only her Brahms and Mendelssohn concertos had been reissued by Testament on CD. Those were the days before we could access any music we wanted with streaming, and so I bought a whole set of the Lexington albums. They were not inexpensive, given the high exchange rate of the yen at the time, but that was only a small fraction of what the originals commanded. Most of her EMI recordings were made at London’s Kingsway Hall with Legge supervising, and the sound is clean, balanced, detailed and with the correct violin tone. I have not heard the originals and so I cannot compare, but judged on their own merit, these reissues are worthwhile. By comparison, they do not have the warmth and glow of the original Milstein LPs from Capitol, but this could be the difference between modern and vintage mastering.

Shortly after purchasing the Lexington reissues, I was pleased to learn that an obsessive Martzy fan in the UK named Glenn Armstrong had set up a new record company in 1997 called Coup D’Archet (strike of a bow) with a mission to enrich her meager discography. He scoured radio stations throughout Europe to look for recordings of Martzy’s radio broadcasts, and petitioned the station owners to license the recordings to him for release on LPs. He was largely successful, thanks to his perseverance. He contracted the mastering and production work to Abbey Road Studios, and a complete analog chain, including a tape recorder with a preview head, was used. These recordings were not reissues, as they had never been available commercially before. The quality of the recordings is quite variable, but they give music lovers an opportunity to hear performances that hitherto have only been heard by those fortunate enough to have tuned in to the broadcasts nearly seven decades ago. He later licensed eight Martzy LPs from EMI and reissued them as a set. You can find more information here: https://www.coupdarchet.com/.

Unfortunately, Armstrong did not reissue the two concertos with Sawallisch, which some critics regard as superior to her collaborations with conductor Paul Kletzki, but these two concertos have been reissued by Lexington on LP, and by Testament on CD.

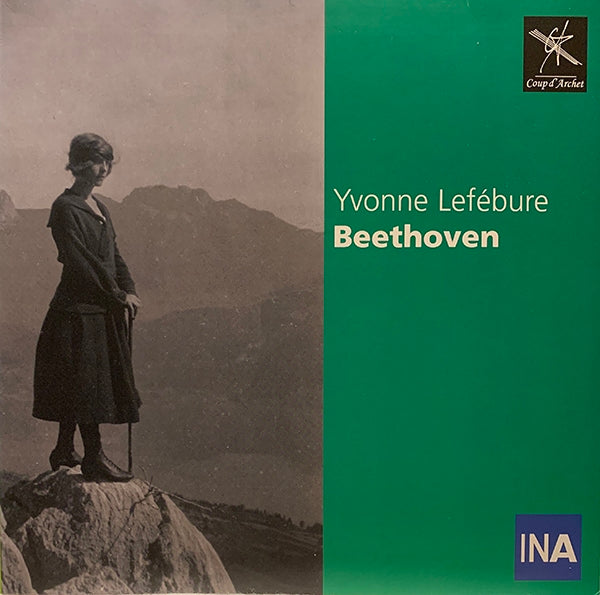

During his search for Martzy recordings, Armstrong also discovered a number of other worthwhile recordings in these radio archives, which he reissued as individual LPs, and as three subscription series of 250 copies each. All the recordings are mono, and most of the artists came from the French school of performance. These include the pianist Yvonne Lefébure, who trained under Alfred Cortot and Marguerite Long. Her reading of the Beethoven Op.111 sonata is powerful and close to my heart. Other pianists in the series include Germaine Thyssens-Valentin, a notable specialist in Gabriel Fauré’s music; Marcelle Meyer, a close associate of Ravel, Debussy, Poulenc and Satie; and Agnelle Bundervoët, one of the greatest pianists to emerge from the Paris Conservatoire. Other notable artists in the series include the violinist Jeanne Gautier and cellists André Levy and Maurice Maréchal. The original commercial recordings of these artists rarely ventured outside the European border, and they are now in high demand on the secondary market.

Yvonne Lefébure, works of Beethoven. LP.

Another obsessive Englishman named Pete Hutchison went one step further and created The Electric Recording Company (ERC) to reissue the Martzy Bach LPs in a way that most closely resembles the originals. He acquired a set of vacuum tube mastering equipment, including a Lyrec tape recorder and an Ortofon lathe with mono cutter heads dating from the 1950s, and spent 10 years painstakingly restoring the equipment to original specifications. Even though both Lyrec and Ortofon are still in business, it is doubtful spare parts are still available, and I suspect many parts had to be remanufactured. I wonder if our own J.I. Agnew was involved? Each release is limited to less than 300 copies, which means the LPs are probably stamped straight from the father in one step. The jackets are faithfully reproduced from the originals, down to the suppliers for the material and the method of printing. Each LP was priced initially at £450 and sold out within hours of announcement. Many of these promptly appeared on the secondary market at two to three times the original price. With my Garrard 301, SME3012, field-coil drivers, directly-heated triode amps and Pierre Clement cartridge, all I need is a tube radio (in wood and Bakelite) and some ERC LPs, and I can make the claim to be a certified Luddite. ERC has since expanded into early stereo and jazz. I have not had the good fortune of hearing any of these LPs, although my recording partner has been given a test pressing of one of the Martzy Bach LPs and has promised to let me hear it one day.

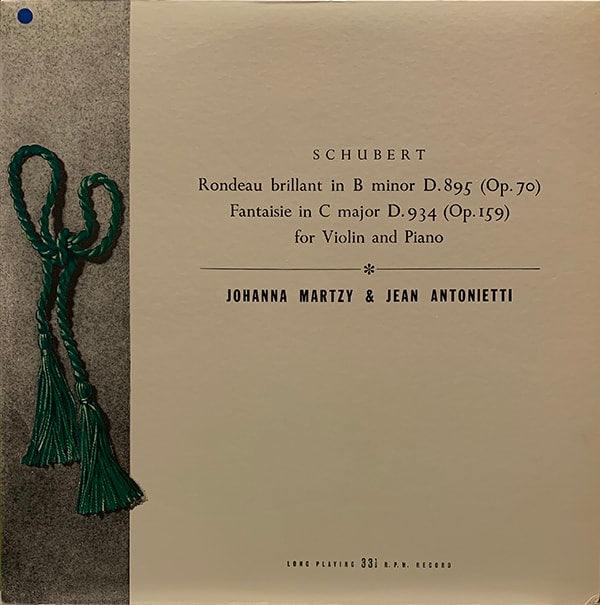

Martzy and Jean Antonietti, works of Schubert, LP.

Talking about Walter Legge, of all the artists he has been associated with, one of the most remarkable was Maria Callas. Callas’s career spanned the mono and early stereo eras, but she started to develop problems with her upper register in the late 1950s. Legge produced almost all of her EMI recordings, and he claimed that he started to notice hints of trouble as early as 1954. One of my favorite recordings, 33CX 1231 (recorded in 1954), include arias from Lakmé, Dinorah, I Vespri Scilliani and Il Barbiere di Siviglia. These are extremely demanding pieces, and I cannot detect any hint of her later troubles in these performances.

Late last year, I heard through the grapevine that an Italian audio magazine called Audiophile Sound, which had already released several LPs of early EMI recordings, has secured the rights to release tape copies from the EMI catalogue. Even though the LPs were mastered from digital files, the tape copies would be made directly from the analog master tapes. The first three tapes due for release include 33CX 1231 and two stereo titles. Intrigued, I got in touch with the editor, a gentleman named Pierre Buldoc. I was prepared to communicate with him in French, since I can’t speak Italian, but Pierre turned out to be Canadian. He is extremely knowledgeable in classical music in general, and in historical recordings in particular. He told me that Abbey Road Studios had made direct 1:1 copies of the EMI master tapes for him, which he will use as production masters to produce his commercial releases. Even though the tapes were not yet ready for release commercially, he was kind enough to make me advance copies of all three titles. I therefore did a back-to-back comparison of the Callas tape with my Testament reissued LP.

Playing the tape with my Nagra T-Audio deck through my tube tape head preamp, the first thing that struck me was the crystalline clarity of Callas’s voice. Even though the sound was bunched into the center (the recording is in mono, and I listened with two speakers), there was good depth perception. In fact, one can hear the layers of instruments, with the voice floating in front occupying its own space. The voice has tremendous body and presence. The dynamic range of the recording is very wide, since unlike many coloratura sopranos, Callas’ dramatic voice could sustain the volume to the extreme of her high register, and the range from the quietest pianissimo to the loudest fortissimo is huge. The background noise of the tape is low, which is remarkable given its age and the lack of any noise reduction technology at the time. I could actually detect tape saturation at one point when she hit a high note with full force. Another remarkable aspect is the transparency, and one can really hear into the recording, clearly distinguishing all the instruments playing behind her even without the stereo spatial cues. The woodwinds have a wonderful tone as one can hear the vibrations from the body of the instruments.

After going through the tape, I turned to the LP. This was played on my Garrard 301/SME 3012 with the Ikeda 9Mono cartridge. The phono preamp is of the same design as my tape head preamp, but built on PCB (printed circuit boards) rather than with point-to-point wiring. Overall, the sound is a little less transparent on the LP. There is less depth, and the voice is not as well separated spatially from the orchestra. The dynamic range also seems a bit compressed compared to the tape, but not dramatically so. At the beginning of “Poveri Fiori”, the strings have a bit less air, and sound less transparent. “Ebben? Ne Andò Lontana” from La Wally sounds a bit less stirring on LP than on tape. On “Cavatina: Una Voce Poco Fà” from Il Barbiere Di Siviglia, the pizzicato strings that accompanied the voice at the beginning sound less dynamic on the LP. It has visceral impact on the tape, even though it is played quite softly. One can feel the vibrations after the strings have been plucked. On the “Bell Song” from Lakmé, when the tambourines come in at around four minutes, one can hear more depth on the tape, and they have more separation from the rest of the orchestra. On the plus side, the LP is tonally indistinguishable from the tape, which means nobody tried to “improve” the tonal balance Legge originally intended. The deficiencies of the LP that I mentioned, if they can be called that, are sins of omission, not commission, and the same cannot be said about some other reissue LPs I have heard.

Maria Callas Sings Operatic Arias, LP.

What accounts for the differences between the tape and the LP? I don’t know how much better the LP will sound if it is played on a record player fifty times more expensive than mine. If anyone is willing to lend me one, please let me know. The tape was made from a production master copied from the studio master, and a lacquer is normally also cut from a production master of the same generation. The mastering process involves an additional cutter head amplifier, the conversion of the electrical signal to a mechanical one by the cutter head, followed by multiple electroplating steps, and finally stamping the grooves onto a lump of molten vinyl. This complicated process no doubt results in some loss of detail, transparency and dynamics. The condition of the stamper when the record was made also makes a difference. That said, the sound of the LP is already excellent, and I would be perfectly happy to live with it if I had not heard the tape.

My last article generated some reader responses. One reader opined that the artists of our generation are technically orders of magnitude more proficient than those of the golden age. I think this is difficult to judge since none of us has heard these golden age artists at their prime. While it is true that people in our era are more perfectionistic, and many recordings from two generations ago would not pass muster if they were made today, we also have to remember that it is far easier to make perfect recordings nowadays. We can easily splice in corrections during post-production, and can even change the pitch and timing of individual notes.

My recording partners and I once made a live concert recording for a violinist whose playing was under the weather that evening. At her request, all the mistakes and pitch problems were tidied up digitally, such that someone who was in the audience that evening would not recognize the performance. Back in the old days, most of the 78 rpm recordings were made direct-to-disk in one take, and the artists were often under pressure to make sure the whole take would fit into one side of the record. Would it therefore be fair to compare recordings of, say, Pablo Casals’s Bach Cello Suites or Artur Schnabel’s Beethoven sonatas to their modern counterparts?

Even then, there were people like Heifetz who seemed to be able to play perfectly under any circumstances. It was a running joke amongst my circle of pianist friends that Alfred Cortot’s greatest asset was the ability to make his mistakes sound musical. My late piano teacher, who was a concert pianist of some renown in his younger days, once told me an anecdote. He attended a Cortot recital where the pianist was totally disheveled and looked ill during the first half. The performance was a mess, with plenty of wrong notes, finger slips and rushed phrases. After the interval, he looked like a new man and played like a god. He was no doubt magically refreshed during the interval.