The rock music biz has had its fair share of power trios, mostly consisting of a front man on lead guitar and vocals, accompanied by a bass guitarist and drummer. The power trio phenomenon became popular with the British group Cream, the Eric Clapton-led group formed in 1966 with a rhythm section of Jack Bruce on bass and Ginger Baker on drums. Though Clapton was placed on a “god-like” pedestal by the rock press and by fans (much to his displeasure), Ginger and Jack weren’t viewed as mere sidemen.

Most power trios, however, are hardly rooted in equality, with a large number having a 1+2 identity, the front man receiving disproportionate credit and recognition. In varying degrees, look no further than the Jimi Hendrix Experience (Jimi Hendrix), Nirvana (Kurt Cobain), The Police (Sting), the James Gang (Joe Walsh), Grand Funk Railroad (Mark Farner), ZZ Top (Billy Gibbons) and the Irish band Taste (Rory Gallagher), to name a few well-known guitar-driven trios.

Certainly there are a range of factors that contribute to a band having a 1+2 identity, including the group’s origins and each member’s leadership, vision, skill set, playing style, writing ability, production skills, stage presence and other factors. In a few instances – and definitely not all – a band’s 1+2 identity is not only unjust, but the unfair disparity has even grown larger over time, especially when a front man moves on to greater success with a new band or solo career (like Sting from the Police to name just one example).

The supergroups Crosby, Stills and Nash (CSN) and Emerson, Lake & Palmer (ELP), though neither considered power trios in the “classic” sense, but trios nonetheless, created a semblance of equality from the very beginning via their chosen band names, though one can envision a squabble or two over top billing. In the case of CSN, the really serious infighting evolved over time. ELP, on the other hand, set out with a more egalitarian solution by alphabetizing the three members’ names.

Among more modern-day artists, singer Brandi Carlile plays in a trio with the twins Phil and Tim Hanseroth, all performing under the name Brandi Carlile. They split everything three ways, and have agreed if the band ever breaks up that Phil and Tim can still perform as Brandi Carlile. Though that may sound like the makings of a gender identity crisis, it’s more about Brandi showing respect and appreciation for her mates.

Of course, the trio concept is more familiar in the jazz rather than the rock world. The traditional jazz trio consists of piano, bass and drums, with the trio often named after the pianist. In 1937 Nat King Cole introduced the piano-bass-guitar trio, while a Hammond B3 organ in place of a piano and bass is also a popular jazz configuration.

One pair of +2 musicians who perhaps haven’t received the public adulation they deserve are the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Mitch Mitchell (drums) and Noel Redding (bass guitar). Although it’s virtually impossible not to fall under Hendrix’s shadow, his aggressive, virtuosic and free-form style of playing did necessitate the accompaniment of a very strong rhythm section. Mitchell and Redding not only were the glue that held the Jimi Hendrix Experience together, they also helped to inspire it.

For this article, I’m especially honoring the Experience’s Mitch Mitchell, as his contributions to the group are particularly undervalued, arguably more than any musician in any other power trio.

Mitch Mitchell.

Mitch Mitchell.

Yes, Mitch Mitchell makes almost every all-time greatest drummer list – from Modern Drummer to Rolling Stone – but those lists frequently are composed by magazine editors and industry insiders, not by the public at large. Among many rock enthusiasts, and certainly casual fans, Mitch Mitchell to this day is still a relative unknown.

Mitchell’s first foray as a professional drummer was as a session player, including a pit-stop with The Who, pre-dating Keith Moon’s arrival. Like several drummers from that era, including Charlie Watts and Ginger Baker, Mitchell was influenced by great jazz drummers, including Elvin Jones, Tony Williams and Ronnie Stephenson.

From 1965 to late 1966 Mitchell played with Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames. Literally the day after leaving the Blue Flames, Chas Chandler, the former Animals’ bass player and then Hendrix’s manager, invited Mitchell to audition for a London-based trio being assembled around Hendrix, who was already gaining a reputation in UK music circles, but still a relative unknown in the US.

Noel Redding was already on board as a bassist, switching from guitar, his natural instrument. Mitchell won out over highly regarded drummer Aynsley Dunbar, with the final selection allegedly decided over a coin toss. The belief was that Mitchell’s fast-driving, jazzy playing fit well with Hendrix’s unorthodox style. Upon hearing he got the job, Mitchell replied, “(He’d) have a go (of it) for two weeks,” not entirely confident this was a sure thing.

Well, he definitely did “have a go of it.” Mitchell was instrumental in creating what is now known as jazz-fusion, with his blending of jazz and rock drumming styles. Just like a classic jazz drummer, Mitchell’s playing not only provided rhythmic support for Hendrix’s music, but also was a source of inspiration and momentum.

Mitchell and Redding played on all three Jimi Hendrix Experience studio albums: Are You Experienced (1967), Axis: Bold As Love (1968) and Electric Ladyland (1968). They also appeared on Hendrix’s posthumously-released studio LP The Cry of Love (1971), though that album was not released as a Jimi Hendrix Experience LP.

Noel Redding. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/A. Vente.

Noel Redding. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/A. Vente.

Mitch Mitchell’s good friend Graham Nash (the Hollies, CSN) shared this amusing anecdote about the very early days of the Jimi Hendrix Experience in London: “Mitch had nowhere to live for a period at the beginning, and I had an apartment, so he just came to live with me for about a year. Jimi would come around a lot and we’d listen to music, though most of all we’d play Risk (yes, the board game). Jimi would drop a few tabs of acid and that was it – nobody could beat him at Risk.”

A drummer who was highly skilled at changing rhythms, and never very predictable, Mitchell was able to respond to Hendrix’s own original solo lines. This was evident on the band’s first album, Are You Experienced, on tracks like “Third Stone From The Sun,” “Fire” and “Manic Depression.”

Fellow drummer Gregg Bissonnette (David Lee Roth, Joe Satriani, Santana) once asked Mitchell out of curiosity if “Manic Depression” was recorded in one take. Mitchell replied, “It had to have been a first take because we were in and out of the studio so quickly. I remember going into a pub the night before and hearing a drummer play a jazz thing in four, and I thought that would be a great beat to put into a 3/4 groove for this ‘Manic Depression’ thing.” They recorded it the next day.

When asked about the song “Fire,” drummer Aaron Comess (Spin Doctors) had this to say, “It’s one of those rock drum songs that everybody plays and nobody gets right. Nobody gets the nuances. He (Mitchell) had a very definable style.”

One of the Experience’s most prominent gigs was their 1967 US debut at California’s Monterey International Pop Music Festival. Mitchell’s recollection of the festival is quite joyous. “It was the first time I’d ever been to America. I can’t tell you what a big deal that was for any English musician, really a dream come true. It was better than I imagined. For Jimi, Monterey was so special as well. He was going back home (to the US) with a band he felt was something special. Playing with Jimi was always instinctive. He gave (me) complete freedom and I would have to say there was a very close link.” The band’s set at Monterey is immortalized in a live Reprise Records LP, Historic Performances Recorded at the Monterey International pop Festival, featuring the Experience on one side and Otis Redding on the other.

Later that same year (1967), the band bizarrely opened for the teen band the Monkees on their first US tour. The Monkees were in awe of Hendrix, and the belief was that a pairing with a cutting-edge band like the Jimi Hendrix Experience would lend some cred to the tour and the band’s reputation.

As the Monkees drummer/vocalist Mickey Dolenz remembered it, “Jimi would amble out onto the stage, fire up the amps and break into ‘Purple Haze,’ and the kids in the audience would instantly drown him out with ‘We want Davy!’ (the Monkees’ vocalist Davy Jones) – God, it was embarrassing.” Hendrix asked for a release from his tour contract, and he and the Monkees amicably parted ways.

Reflecting on the Monkees tour, Mitchell had this to say: “We discovered that Peter Tork could play banjo, Mike Nesmith could play guitar, Micky Dolenz was one hell of a nice guy, and Davy Jones was extremely short. The gigs all in all were okay, but by about the third day Davy Jones really started getting on our nerves. Noel (Redding) discovered he had an amyl nitrate capsule, which he claimed belonged to his grandmother for her heart condition. He broke it under Davy Jones’ nose, who passed out on the floor. It was a sight to behold. I’m glad we did the tour as it was something I would never have experienced otherwise.”

The release of Axis: Bold As Love (1968), the band’s second album, was almost delayed when Hendrix left the master tape of side one in the back seat of a London taxi. With the deadline looming, the entire side had to be remixed, but they could never replicate the quality of the lost mix on the song “If 6 Was 9,” much to Hendrix’s disappointment. Regrettably and unfathomably, no safety copies had been made before the taxi fiasco.

With the “If 6 Was 9” remix, the engineers had to reference a damaged tape from the original session that Noel Redding had in his apartment. But they first had to smooth out the wrinkled tape with a shirt iron to hear how the original mix sounded. The real challenge, however, was replicating the song’s layered guitar work and effects, which they never quite got right. They just couldn’t get the feel and sound of the original master.

Of course, revisionist history and conspiracy theorists have had a field day with this long-told taxi tale, some going as far as saying Hendrix intentionally left the master in the cab because he didn’t like the mix.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s final studio album is the truly classic Electric Ladyland (1968). During this period, Hendrix increasingly felt more comfortable and confident in a studio setting, which ultimately lead to a parting with both manager/producer Chas Chandler and bassist Noel Redding. The sessions were described as chaotic, as many friends dropped in and participated, including Steve Winwood, Brian Jones, Dave Mason, Jack Casady and Al Kooper.

With Ladyland, Jimi was enamored with the era’s relatively new 16-track recording technology, and he desired to take full advantage of its capabilities. Both Chandler and Redding were a bit inflexible with Jimi’s experimentation with multiple takes, overdubs and mixing techniques. Hendrix now viewed the studio not as a place to just record, but to develop new material and to experiment. He no longer was just a musician; he had also become a producer.

Noted Mitchell, “With Chas and Noel, it was ‘let’s get it done,’ but I was more okay with take after take. In my role with Jimi, I had an immense amount of freedom to throw ideas, and likewise back and forth, while Noel did an extremely good job of holding down, or keeping a pulse. Noel was more than a competent guitarist (his natural instrument), but bass guitar was never a particular instrument that he loved.”

As Redding recalled, “There were tons of people in the studio; you couldn’t move. It was a party, not a session.” When Hendrix started to record some of the album’s bass parts, it created tension between him and Redding, though Noel had already begun to stretch out with a new side band, Fat Mattress, in a more comfortable role as lead guitarist and vocalist. (Note: Fat Mattress opened for the Jimi Hendrix Experience on several occasions, requiring Redding to play sets with both bands.)

Hendrix biographer and producer John McDermott had this to say: “When you listen to outtakes from the Electric Ladyland sessions, initially there’s just Jimi and Mitch with bass added in later. There was a relationship between Jimi and Mitch that was really unique and supportive, and at the same time they challenged each other. Mitch wasn’t there to just take direction. Jimi wanted him to bring his skill and talent to the fore.”

Electric Ladyland certainly captures Jimi’s desire for experimentation, from “Voodoo Chile,” to “Burning of the Midnight Lamp,” to his arrangement of Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower.” Said Mitchell, “Jimi really admired Dylan as a lyricist. In the early stages of a band you’re finding [out] about everyone’s tastes, musically or otherwise. I’d turn him (Jimi) on to John Coltrane, Roland Kirk or Miles Davis. At the same time, he’d turn me on to Dylan. Of course, I was aware of Dylan for many years, but I never paid attention to his lyrics. Jimi was never afraid of a new direction, and that appealed to me (both as an artist and a drummer).”

When asked about “All Along the Watchtower” and Hendrix’s evolving perfectionism, engineer Eddie Kramer (the Beatles, the Kinks, Small Faces, Traffic) had this to say: “It’s (Watchtower) a great example of an artist of Jimi’s stature starting from square one with a very difficult arrangement. He’s yelling at Mitch (Mitchell) to get the beat right, and then at one point Brian Jones walks into the studio drunk out of his mind and starts to play piano. Jimi politely lets him play, I think on take 20 or 21, and then excuses him by saying, ‘No, I don’t think so, Brian.’ Then by take 25 it’s a four-star, take 26 is good, but take 27 is the master, you can just tell. Everything is perfectly placed and has the intensity that Jimi wanted, so the song evolved because it had to.”

Of course, soon thereafter Hendrix created another power trio, the Band of Gypsys (1970), with Buddy Miles on drums and Billy Cox on bass. Their lone album fulfilled a Hendrix contractual obligation, though the band had limited rehearsal time prior to the live recording captured over four shows at NYC’s Fillmore East. The album received mixed reviews, and Hendrix allegedly wasn’t particularly happy with it. Though the late Buddy Miles indeed was a good drummer, with more of an R&B style, he lacked the flair and improvisational skills of a Mitch Mitchell. In fact, listening to the Band of Gypsys LP by comparison points out – perhaps unfairly given the Gypsys’ short tenure – the progressive skills Mitch Mitchell brought to the Experience.

Both Mitchell and Redding went on to play with other bands and projects. It later emerged that Hendrix’s co-manager, Mike Jeffery, had cut both out of royalties, demoting them to paid employees. This led Mitchell and Redding to have to sell off any legal claim to future Hendrix record sales, including the sales of CDs that reinvigorated income for many legacy artists.

John “Mitch” Graham Mitchell died in 2008 at the age 62, and David Noel Redding in 2003 at the age of 57.

In sum, neither Mitchell or Redding could be credited or acclaimed on the same level as the great Jimi Hendrix, but their contributions and collaborations with the Experience, and Mitch Mitchell’s in particular, deserve far greater recognition than what’s generally acknowledged.

In sum, the Jimi Hendrix Experience was most definitely not a 1+2 band.

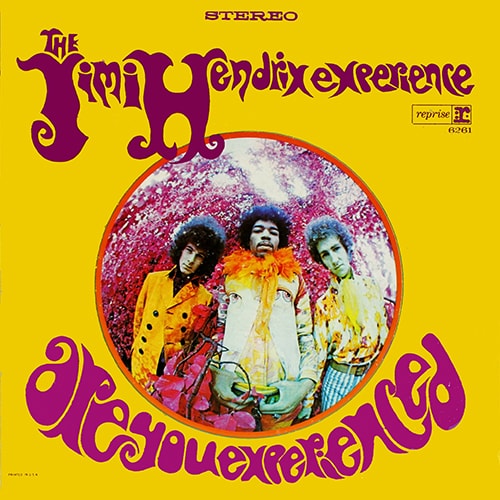

Header image: The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Are You Experienced album cover, featuring Noel Redding, Hendrix and Mitch Mitchell.