Back in the 1980s or maybe earlier, “transparency” became the buzzword in high-end audio. Harry Pearson of The Absolute Sound was a big proponent of the term, and soon many reviewers and sycophants jumped on the idea, to the point where talking about “transparency” quickly became a tiresome cliché.

But what does “transparency” really mean?

I think most audiophiles consider transparency as having a clear window into the sound; the visual analogy being pretty much perfect here. The music is heard unobscured, rather than through a grimy sonic “window.” (Of course, our systems can only sound as good as the quality of the recording.) Certainly, we know when a component or system is not transparent – it lacks detail, spaciousness, depth and “life,” and can sound uninvolving.

Conversely, systems that let us hear deeply into the music (sometimes literally, if the recording has a deep soundstage) are considered to be transparent. Fine musical detail is revealed, often to an astonishing degree, whether it’s the way a guitarist will fingerpick each note a little differently, or the ability to hear the sound of a symphony orchestra bounce off the concert hall walls. The line between hearing a “hi-fi system” and the illusion of experiencing “real life” is thin.

Symphony Hall, Birmingham, England. On a good, transparent recording and system, you can get a sense of a hall’s acoustics. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/JimmyGuano.

However, I don’t think transparency is necessarily the same as better resolution. But surely, if a system lets more detail through, we hear more, and it’s more transparent, right? Maybe there’s more to it.

I can’t be the only one who has mistaken brightness as better resolution, especially when first swapping a component, cartridge or cable that has more of an upper-midrange and treble emphasis than the one previously in the system, and being enamored of all the new sonic “detail” that’s “revealed.” But it’s often just an illusion of better resolution. (On the other hand, rolling off the treble will reduce sonic information.) How to tell the difference? Listen to known reference recordings to hear if you really are getting more detail, or simply more brightness.

No-brainer time: noise is the enemy of transparency, whether hum, buzz, powerline interference, tube noise, record noise or some other type of unwanted overlay. Sometimes low-level noise is insidious, and we don’t hear its effects until it’s reduced or removed. It’s the phenomenon of hearing the music against that “blacker background” that reviewers love to gush about.

Maybe some measurements-are-everything guy or gal would just tap me on the shoulder and say, “hey pal, why are you wasting everyone’s time going on about this? Just measure the input and the output waveforms and whatever distortion is present in the output is your lack of ‘transparency,’ right there.” But I think there’s more to it than that.

I think we have to consider the idea of dynamic transparency. Sure, it’s probably the same as dynamic range, and I’m probably just being too clever by half here, but recordings and systems that offer greater dynamic contrasts absolutely sound more real, involving and yes, more “transparent” to me.

Transparency can vary across the frequency range. It shouldn’t be considered some overarching thing that’s applicable to a recording or system as a whole. For example, I think we’ve all heard systems with articulate bass, and with muddy bass, and no one would argue the former is more transparent. How much of this is a result of the system’s resolution and how much is the effect of the room on the quality of the low frequencies? Good question. Oh boy, now we’ve got to deal with the concept of transparent rooms! Maybe I can get Bob Katz or Carl Tatz or somebody like that to weigh in on this in a future issue.

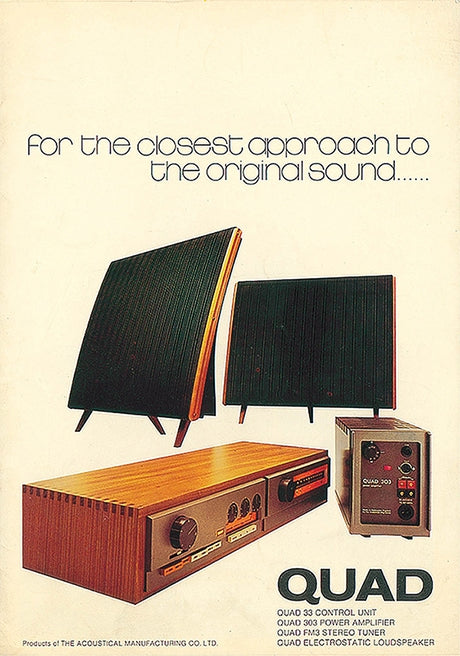

Can we even agree on what audio components offer greater or lesser transparency? I’ve always prized the sound of a good electrostatic or ribbon or plasma tweeter. I doubt I’d find any audiophile who’d disagree that the words “Quad ESL” and “transparent” go hand in hand. But then there’s the age-old, perhaps-never-to-be-resolved debate about vacuum tubes. Every 300B-based tube amplifier I’ve ever heard has had, for me, an almost spooky kind of you-are-there realism, a sense of hearing deeply into the sound. Is it because of the transparency and linearity of a 300B, or am I being fooled by harmonic distortion?

1960s Quad advertisement showing the classic ESL loudspeaker.

I’ll leave with this thought. One of the definitions of “transparent” is “easy to perceive or detect.” So, according to this less-common usage of the term, perhaps any audible improvement in an audio system essentially an improvement in transparency.

Russ Welton offers his thoughts on the subject in Issue 132.

Header image courtesy of Pexels.com/cottonbro.