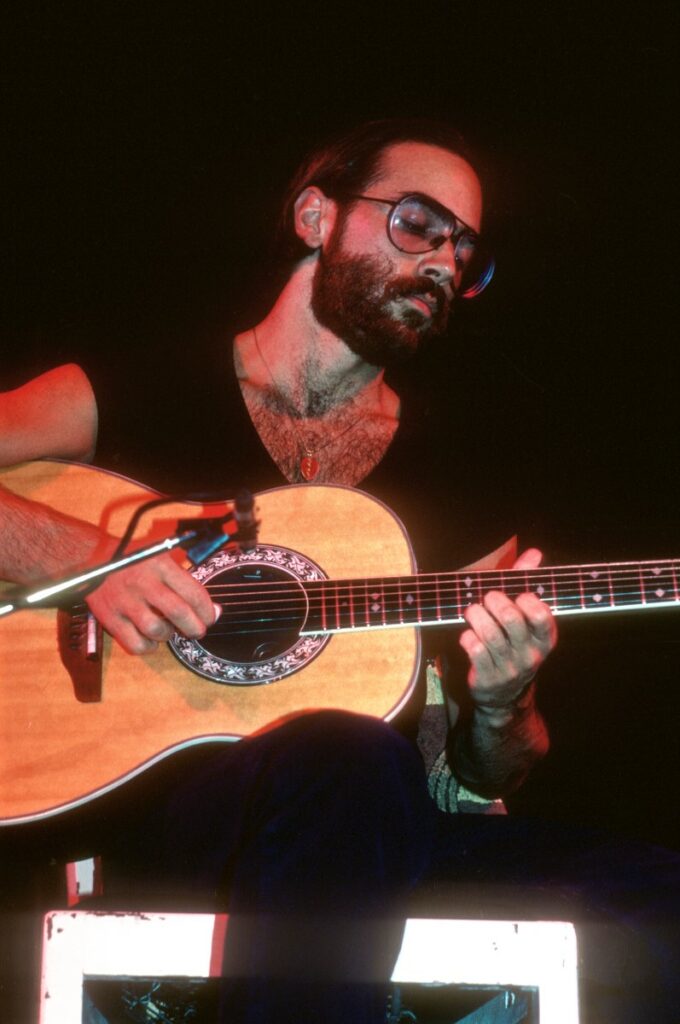

In the mid-seventies, Al Di Meola was a young, hotshot jazz fusion guitarist with Chick Corea and Return to Forever. But he’d also developed a deep understanding of Latin music, and had a special love for flamenco guitar. During a European tour with RTF, Di Meola heard of a legendary Spanish flamenco guitarist, Paco De Lucia. Determined to hear his music, he visited a local record shop during the Spanish leg of the tour and bought all the Paco De Lucia albums in stock. And just about wore the LPs out listening to them. As he was getting ready to record 1977’s Elegant Gypsy, Di Meola informed an A&R contact at Columbia Records that he wanted to do a duet with De Lucia on the album. The label reached out to De Lucia, and despite speaking no English, he came to Electric Lady Studios in New York where he and Di Meola worked out the Flamenco duo “Mediterranean Sundance.” And the experience was a blast for both of them.

Paco De Lucia was a classic flamenco guitarist and incorporated elements of jazz and classical in his playing. He and Di Meola worked very well together on “Mediterranean Sundance,” which became a surprise hit, charting in both Spain and Germany. Al Di Meola expressed his desire to work more with De Lucia, and Al’s promoter Barrie Marshall began working out the details. Which included a possible guitar trio with De Lucia and Leo Kottke; Di Meola questioned the choice of Kottke, and Marshall eventually came back with John McLaughlin as a suggestion. McLaughlin early on had become smitten with flamenco music, and often traveled great distances to hear flamenco players perform. But his career took a very different path, having been built working with Miles Davis during the Bitches Brew period and his own Mahavishnu Orchestra and the Indian-inspired Shakti.

In an instance of complete happenstance, John McLaughlin had his own “Paco De Lucia” moment. While driving through Paris, he heard a De Lucia tune on the radio, and became determined to work and record with him. And as it turned out, Paco De Lucia was also in Paris. The two played together, and their chemistry was undeniable, but they both felt they needed a third guitarist. After an early tryst with Larry Coryell didn’t quite gel, they eventually teamed up with Al Di Meola, and in 1980 after months of preparation, departed on a two-month tour of Europe and the United States. The final two dates were in San Francisco, and Di Meola contracted Tim Pinch of Pinch Recording to do remote live recordings of the two shows on Friday and Saturday, March 5 and 6.

Friday Night in San Francisco

Those recordings generated the now-legendary Friday Night in San Francisco album. Which was released on August 10, 1981, after Al Di Meola badgered Columbia Records to the point where they caved and released it. The album had surprising cross-cultural appeal, going platinum and selling millions of copies. It has gone on to become an audiophile perennial favorite. In 2017 it was reissued by Impex Records as a 180-gram, 33 rpm LP, then again in 2020 as 180-gram, 45-rpm, 2-LP limited-edition numbered sets. Those Impex reissues were massively successful, and received many industry accolades for their overall excellence, but especially for their impressive sound quality.

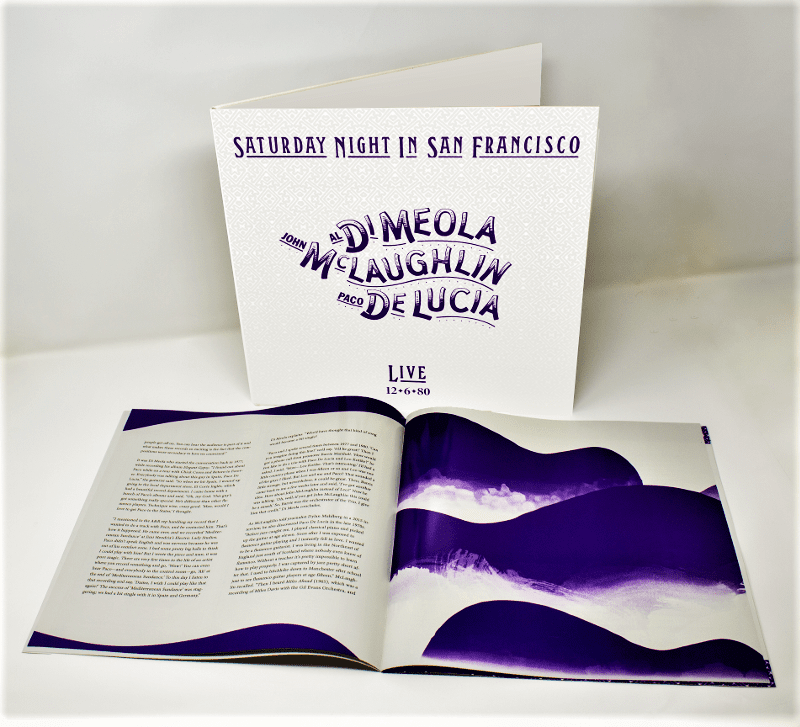

Later in 2020, Abey Fonn of Impex Records was contacted by John Jackson, then head of Sony/Legacy, to gauge her interest in a Saturday Night in San Francisco project. Which mystified Abey; she knew that there was a second night in San Francisco — you could even see YouTube videos of parts of the Saturday show. But there was no album; did tapes even exist for the Saturday night show? John responded that yes, the tapes existed, and Al Di Meola had them in his studio all these years. Al and his manager Gary Casson approached Sony/Legacy because there was such a wealth of unheard music on the tapes — it wouldn’t just be a rehashing of alternate takes from the Friday night show. Because Al had paid for the original recordings, he owned the tapes, but because he was under contract to Sony, he had to offer them first right of refusal. Sony/Legacy wasn’t feeling it, apparently, so John Jackson offered the project to Impex Records — and Abey Fonn jumped at the chance!

Impex Records put together a YouTube video that details the entire process from start to finish. It’s really great to see and hear insightful comments from Al Di Meola, Abey Fonn, Chuck Granata, Roy Hendrickson and most everyone else who helped make this astonishing release possible. It’s definitely an informative and entertaining watch.

Saturday Night in San Francisco

When Abey Fonn assembled the team to handle the Saturday Night in San Francisco reissue, she and Bob Bantz (her partner and owner of Elusive Disc) served as executive producers; Al Di Meola was the producer, and Charles “Chuck” Granata served as co-producer. Chuck also wrote the liner notes in the excellent and informative booklet that accompanies the LP, SACD, and CD (the LP booklet wins hands-down here, strictly on size alone!). Al wanted to use his personal engineer, the well-respected Katsuhiko “Katsu” Naito, to edit the tapes, and a transfer from the original 16-track master tapes was ordered. Here’s where the production team hit the first snag: the initial transfer was deemed unacceptable. The tapes seemed to be particularly lacking in ambience when compared to those for Friday Night in San Francisco. Abey Fonn didn’t believe that the essence of the live performance present on the master tapes had been captured by the first transfer.

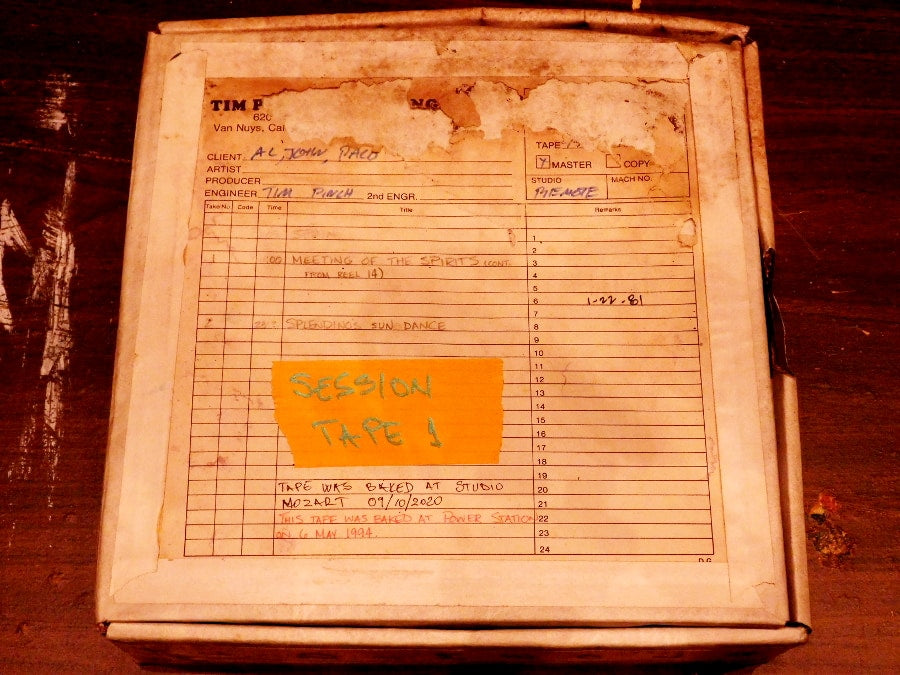

The original master tapes showed signs of water damage and minor mold spore growth.

The original multitrack master tapes from Al Di Meola’s studio were in somewhat fragile condition; they showed signs of water damage, and some of the reels had some slight mold-spore growth. Obviously, their long-term storage conditions had not been optimal. There were definite concerns that even after cleaning and baking the tapes, some oxide shedding might still occur. And it was brought to the attention of the team that one of the tape machines used in the original recording had gotten progressively slower as the Saturday night recording process went along. This caused some harmonic shifts in the music; it was clear to everyone involved in the transfer process that they’d probably only have one clean playback of the original multitrack tapes to create a new multitrack master. It was decided at this point to bring in Ulrike Schwarz to provide expert assistance in overseeing the transfer process. Ulrike suggested to Abey that their best option was to use Skywalker Sound in Lucas Valley, California. Skywalker’s expertise in tape restoration is legendary, so the tapes were sent there post-haste. They’d be cleaned and baked prior to beginning the transfer process, which would take place on a Studer A800 open-reel recorder. Ulrike had most of her equipment shipped to Skywalker Sound in advance, where everything else necessary to achieve the transfer would be waiting on site.

The master tapes were cleaned and baked in the ovens at Skywalker Sound prior to the transfer process.

Of course, this all began during the emergence of the pandemic, so much of the oversight of the transfer process might have needed to be done remotely. And Skywalker had a rigid COVID policy in place, which strictly limited the number of visitors to the facility. However, with Ulrike’s excellent longstanding working relationship with the studio, she was able to personally attend, working with Skywalker’s Dann Thompson while she supervised the transfer. After the tapes had been cleaned and baked, the process hit another snag: the master tapes had no calibration tones. Without those tones, it would be difficult to achieve correct head alignment on the Studer recorder. Ulrike’s team contacted Tim Pinch (who made the original recordings); he told them that a 3M recorder had been used in his mobile truck, which was very common back in the day. Armed with that information, they reached out to a source in LA who provided a number of different alignment tapes to assist in getting the Studer set up. On the third alignment attempt, they hit pay dirt, and the transfers were finally underway.

The master tapes for the Saturday Night concerts had not been stored under optimal conditions.

The 16-track tapes were successfully transferred using the now perfectly-aligned Studer A800. The Studer is a very forgiving machine, and handles tapes gently with great consistency of speed. For Ulrike, it had become increasingly obvious that the poor condition of the original tapes would only allow a single pass through the A800. She maximized this by transferring the 16-track masters to 32-bit/384 kHz ultra-high resolution digital, which would offer an exact replica of the original master tapes. It would also allow for easy correction of the tape speed fluctuation caused by the faulty 3M tape machine used on the original location recordings in San Francisco. The new 32-bit/384 kHz multi-tracks would also facilitate the production of surround-sound mixes for SACDs, if so desired. Impex Records ultimately put plans for a surround mix on hold, so the new tapes would only yield LPs, stereo hybrid SACDs, and CDs.

Roy Hendrickson, Katsu, and Bernie Grundman Take the Helm

The new multitrack reels were then shipped from Skywalker to Roy Hendrickson’s Spin Recording Studios in Long Island City to begin the editing process. In choosing a new engineer to perform the editing and mixing, Abey wanted to enlist someone Al Di Meola would be confident working with and who would be a good team member. Impex’s attorney, Andrea Yankovsky, recommended Roy for the job; they’d both worked together at Power Station back in the Nineties, and she was positive he was perfect for the job. When Roy began the editing process with the new tapes, Katsu Naito was brought in as a consultant. Al really wanted to be involved, but was on tour at that point and couldn’t be present. Al had worked closely alongside Katsu to edit the first transfer (that was ultimately discarded), and he trusted Katsu implicitly. Katsu’s invaluable knowledge of the edits on that first transfer was instrumental in helping Roy’s editing achieve the level of exactitude Al expected. I spoke at length about the sessions with co-producer Chuck Granata; he’s local to Al in New Jersey, and was present in the studio for much of the editing and mixing. Chuck told me that he didn’t take a very heavy-handed approach to the process, but it was good to have an impartial voice present in the control room to insist that they “remove the occasional audience cough.” We have the technology, we can make it better, right?

The new 32-bit/384 kHz multi-tracks were used for editing and tape speed fluctuation correction. Before the final mix process commenced, Roy listened to Friday Night in San Francisco multiple times to create a baseline for his mixing approach for the new record. He realized very quickly that he knew many of the personalities at the studios who were involved in its original production. He didn’t hesitate to reach out to them to get valuable information regarding the pertinent technical details and equipment they were using at the time. Roy had soon acquired all the necessary vintage analog processing and effects equipment needed, and his all-analog mix was made using an analog console. Which would ensure that Saturday Night in San Francisco was every bit the sonic triumph that its predecessor had been! Roy’s final mix was reduced to a 2-track, half-inch stereo analog tape on heavy-duty precision reels; those were ultimately sent to Bernie Grundman for final mastering.

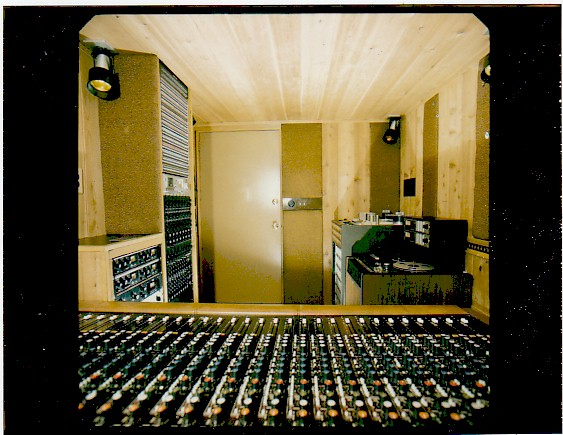

In my conversations with Chuck Granata, he shared a wealth of information about original recordist Tim Pinch, who learned his craft working for Wally Heider in Los Angeles. Pinch made the recordings in his custom-built remote truck, which had been a fruit delivery truck in a previous life! He even hired the same guy who built Wally Heider’s custom consoles to outfit his mobile truck’s interior. While the Pinch Recordings truck was rudimentary compared to those of the bigger studios, it produced exceptionally good-sounding tapes. Tim Pinch made his bread and butter by recording lots of live-for-television events, like the Golden Globes, the People’s Choice Awards, the American Music Awards, and the Super Bowl halftime show, and eventually got the contract to record the King Biscuit Flower Hour radio series.

An interior shot of Tim Pinch’s remote recording truck.

Chuck described Tim’s microphone placement for the sessions, and remember — these were 16-track tapes used to record only three performers on stage! Tim placed mike stands that held two mikes each for each player; one mike near the guitar’s soundhole, and one near the guitar’s fretboard. The acoustic guitars were amplified (necessary because of the size of the hall), so he also recorded a direct feed from each amplifier going into the soundboard. He then placed several mikes facing the audience to catch close-up crowd sounds, and several mikes toward the rear of the hall to help reinforce the sense of ambience in the recording. That easily accounted for all 16 channels, and Roy Hendrickson did a masterful job of mixing all those channels into a cohesive document of the live event. The recording captured not only the magnificent playing of the trio, but also the ambient cues of the venue that give this recording such an ethereal and immersive feel. Chuck told me that despite only being a guitar trio recording, the sound on the tapes was so immersive and mesmerizing in the studio that he had no problems envisioning it as a surround recording.

When Roy’s final remixed half-inch master tape was presented to Abey Fonn, everyone at Impex had a listen, and they all knew that they now had the Saturday Night in San Francisco they’d been hoping for. The tapes were shipped to Bernie Grundman Mastering for final preparation for LP and SACD production (Bernie also handled the final mastering on Impex’s Friday Night in San Francisco reissues). Abey and her QC specialist, Bob Donnelly, arrived to oversee the proceedings and to have a listen with Bernie. Everyone was thrilled with the results, and test pressings were then listened to on multiple audio systems before giving the go-ahead. Thumbs-up was the consensus; RTI’s presses started cranking out the LPs, while SACD and CD production was sent to Sonopress in Germany.

The Final Products

My LP arrived in mid-June. I have a lot of experience with audiophile reissues of every sort, and it’s not a stretch to say that Impex LPs are among the ne plus ultra of the reissue game. That proclamation extends not only to the incredible sound of Impex LPs, but to all of the associated packaging and jacket production as well. Having an extensive background in commercial art and print production gives me a much greater appreciation for the fabulous job that Robert Sliger did with the jacket and packaging for Saturday Night in San Francisco. This job was obviously a labor of love for him, and it completely shows through in the meticulous level of detail in the finished product.

Robert Sliger’s jacket and booklet design is the icing on an already beautiful package.

From the heavy card stock, tip-on style gatefold jackets and the use of metallic inks in the print process, every aspect is of highest quality throughout. The LP was perfectly flat, and had exceptionally glossy, pristine surfaces that showed no scuffs or marks of any kind. The attention to detail even extended to the album’s label, which not only incorporated the newly-designed artwork, but also included the classic chain of Columbia logos encircling the label’s perimeter. Giving the LP a new but also very vintage feel!

Production of the SACDs encountered slight delays, and a finished disc didn’t arrive by my deadline. But no worries — Abey Fonn saw to it that Gus Skinas sent the DSD files that were created for the SACDs from Bernie Grundman’s final master. And I have no doubt based on my experience with previous Impex SACDs that the packaging for those discs will be just as impressive as for the LPs — just a wee bit smaller in scale!

System Setup

The system I ended up choosing for this task was based around the new KLH Model 5 loudspeakers. The Model 5s supplied vintage authenticity to the proceedings and sound superb, even though they’re a more modern twist on Henry Kloss’ original vision. Amplification was provided by my PrimaLuna EVO 300 tube integrated amplifier, which features a quad of EL34 output tubes. I generally always choose triode output when listening to acoustic sources, and with both the LP and digital files for this project, that proved to be the correct choice.

The Pro-Ject Classic EVO with its Hana SL cartridge was the perfect match for this excellent album.

My analog front end employs a Pro-Ject Classic EVO turntable that’s fitted with a Hana SL low-output MC cartridge. The analog signal is fed into a Musical Surroundings Phonomena II+ phono preamplifier that’s powered by its own linear power supply. Digital playback features the Euphony Audio Summus/Endpoint server, which streams via i2S to Gustard’s flagship X26 Pro DAC. It’s paired with Gustard’s C18 Constant Temperature 10MHz Master Clock; the digital stack offers a level of musically seductive sound that gives analog a real run for the money!

Listening Results

I’d been listening to the Saturday Night in San Francisco LP for a week or so. When I finally got access to the DSD files, my critical listening was done by alternating between analog and digital sources. To get a good sense of how they compared sonically. I always rip the DSD files from an SACD to my digital music server, then play them through my Euphony/Gustard digital front end with an i2S connection. It’s much more transparent and revealing than the internal DAC of my standalone SACD player. Getting the DSD files from Impex was perfect for me; I simply loaded them onto my server and we were off and running!

I’m a huge fan of analog playback; in my opinion, great analog — warts and all — usually wipes the floor with great digital. That said, I’ve been over the moon with my digital front end now that the master clock is in place. The master clock adds a level of refinement to digital playback that the DAC alone can’t match, with improved musicality, more impressive dynamics, and a more well-defined soundstage and stereo image. My recent experiences have shown me that exceptional digital can come awfully close to the analog grail.

The Gustard X26 Pro DAC and C18 Master Clock placed my digital front end on equal footing with the analog setup.

So I was surprised when the DSD files sounded different when compared to the LP. Chuck Granata asked if I’d had a chance to take a listen to the LP and the digital files, and I told him that I had, and definitely gave the nod to the LP versus DSD. But when I really started listening critically, the sound I was hearing from the digital source didn’t match what I was hearing from the analog source. Then it hit me: Gustard employs an odd pin configuration in their implementation of i2S that reverses the output channels. I had neglected that while making the connections to the PrimaLuna tube amp. It only took a moment to get the sound perfectly synchronized between the sources, and everything quickly snapped into focus. From that point on, I found it difficult to find significant differences between the sound of the two formats!

The performance opens with a spoken introduction from the late Bill Graham; Al Di Meola insisted that it be included on the reissue. Di Meola saw many shows at Graham’s Fillmore East as a young man, and those experiences totally shaped his vision as a musician. He developed a lasting friendship with Bill Graham, and always had the greatest respect for him. Al Di Meola has always maintained that the two nights in San Francisco were very special, easily transcending the other dates on the tour. The simpatico between the trio was at its pinnacle; the three men had taken their playing to the next level on those two nights.

John McLaughlin takes the evening’s first solo turn on Saturday night.

Di Meola really appreciated that the San Francisco audiences were so vocally supportive and receptive at the shows. The audience irrepressibly screams and cheers, and through Tim Pinch’s superb recording and Roy Hendrickson’s immersive mix, that audience participation gives you a really great impression of the acoustics of the Warfield Theatre. In my room, the soundstage spreads far behind and beyond the sides of the KLH Model 5s, and even extends to the left and right of my listening position, which is about 12 feet triangulated from the face of the speakers. It’s pretty astonishing!

Al Di Meola takes the second solo turn on Saturday night.

Side One’s music begins with a trio track, the Al Di Meola composition “Splendido Sundance.” The track features some incredible interplay between the three musicians, and sets the stage for the solo performances that immediately follow. John McLaughlin’s “One Word” isn’t classically flamenco, but his playing is rhythmic and propulsive; the crowd loved it, and he’s in the center of the soundstage. Al Di Meola’s on the right; his “Trilogy Suite” alternates between intricate finger picking and fiery massed chords. At what appears to be the end of his piece, the crowd roars with approval, and then he comes back for even more! Paco De Lucia’s “Monasterio de Sal” features intricate and also delicate finger picking, and is more pastoral in feel than the first two offerings; he’s located on the left of the soundstage. As with the other solo performances, the audience loudly expressed their appreciation. During the solo performances, you get more of a taste of each players’ individual style, but during the trio performances, they all play with a bit more reckless abandon.

Paco De Lucia took the final solo turn on Saturday night.

Side Two of the LP consists of entirely trio performances, and opens with Paco De Lucia’s “El Pañuelo,” which begins with extended (and very percussive!) finger-tapping on the guitar surfaces by all three players. This transitions into a much more fiery and boldly expressive flamenco tune with plenty of intricate finger picking from all three musicians. That’s followed by John McLaughlin’s sprawling “Meeting of the Spirits,” which is more idiomatically flamenco than his solo turn, and includes ridiculously rapid-fire soloing from each member of the trio. The audience roars with enthusiasm throughout the trio performances. Al Di Meola mentioned in the liner notes that it was truly refreshing for the San Francisco audience to so actively participate — the Los Angeles audiences were far less enthusiastic, essentially saying to the performers, “Yeah? So what else have you got?”

The SACD disc includes an exclusive bonus track, Paco De Lucia’s solo turn on his own “Soniquete.” His performance here is fiery and filled with bravado; it’s a fitting conclusion to this album that was a labor of love for Al Di Meola. The album is dedicated to the late Paco De Lucia, and Al Di Meola wanted his contributions highlighted, especially with the inclusion of the extra track.

Conclusion

Saturday Night in San Francisco is an astonishing album, and even more so that it’s only now seeing the light of day after 40-plus years! Every member of the Impex team gets nothing but praise for their efforts here. Especially Roy Hendrickson, for his phenomenal job on a final mix that really immerses the listener within the live event; this is about as “you-are-there” as it gets for a stereo recording! The LP surfaces were whisper-quiet during playback, with only a few ticks along the way that tended to get polished out with repeat playings. Groove noise was virtually nonexistent; this LP definitely resides in the upper echelon of the analog experience. Hats off to Bob Donnelly for his quality control efforts, to Bernie Grundman for the perfection of his final master, and to everyone at RTI for producing such an amazing LP.

While my usual preference almost always leans toward the analog side, the outstanding DSD presentation of this album makes it impossible for me to make a firm choice. Both the LP and DSD files are remarkable documents of this live event; they’re undoubtedly among the best of the best! Constant A/B’ing between the LP and DSD files revealed no discernible differences, other than the very slight hissing of the analog phono stage during playback. The backgrounds of the DSD file were completely dead silent, which is remarkable for a 40-plus year-old live recording. Saturday Night in San Francisco from Impex Records comes very highly recommended — if you’re a fan of the original album, this one is an indispensable companion to that excellent recording and a must-have. Don’t hesitate, it’s sure to sell out very quickly!

Impex Records: (1) HQ-180 33-rpm LP (catalog #IMP6045), MSRP $39.99; SACD hybrid (catalog #IMP8324), MSRP $29.99.

Available from Impex Records: Saturday Night in San Francisco, Friday Night in San Francisco, and Saturday Night in San Francisco is also available from Elusive Disc.

All images courtesy of the author, Impex Records, Abey Fonn, Chuck Granata, and Ulrike Schwarz.