Ken Kessler revels in the stories told by scraps of paper found in tape boxes

However old the tapes, however worn and unloved, nothing amuses or delights me as much as finding the inserts intact in the boxes for those I’ve been salvaging. It’s like finding the prize in a cereal box (or Cracker Jack, when it was worth having). They tell me much about the earliest days of hi-fi and stereo and separates, even though I could get the same information by curling up with the oldest hi-fi magazines in my library, or simply trawling the internet.

But it just ain’t the same: these slips of paper are physical artifacts which would have greeted the original owners a lifetime ago. This audio archaeology is a dimension of the hobby I never quite realized how much I relished, despite having found myself dubbed “a hi-fi historian” by virtue of the few books I’ve written. That said, access to the archives of a manufacturer to curate a company’s history isn’t the same as the surprise when a catalog or coupon lands on the floor, upon opening yet another tape box which had probably lain undisturbed since LBJ was in office.

There are myriad treasures to be found in those old cartons, little time capsules like the catalogues from Capitol, which aid the curious by featuring on them the actual month and year they were issued. RCA and Columbia and Bel Canto – they just incite more lust for tapes I might never get to hear. Then again, I suppose that was their raisons d’être.

Of late I have been bemoaning the passage of time with each arthritic creak, and the demise of dear Queen Elizabeth II made me appreciate in spades that I have lived in the UK for a half-century, so seeing items decades past their sell-by date does nothing to help me dispel notions of mortality. But curiosity always gets the better of me, and I am lost in a reverie, an audiophile fantasy wherein I could send off to Tape-Log for a free subscription, or tap Ampex for a $1 discount.

A typical package’s inserts, this one from Tape Mates.

Ampex voucher for $1 off your next tape purchase.

Such inserts fall into a number of categories, the most plentiful and obvious being label catalogs, followed by newsletter subscriptions and, as mentioned above, the odd coupon, etc., but the ones which serve the most value for hard-core tape fetishists have to be the technical sheets. I’ve scanned two here to show you just what they used to do for music lovers and audio enthusiasts in the old days. (STS: are you paying attention, ye of the least-informative liner notes in the entire pre-recorded open-reel tape business?)

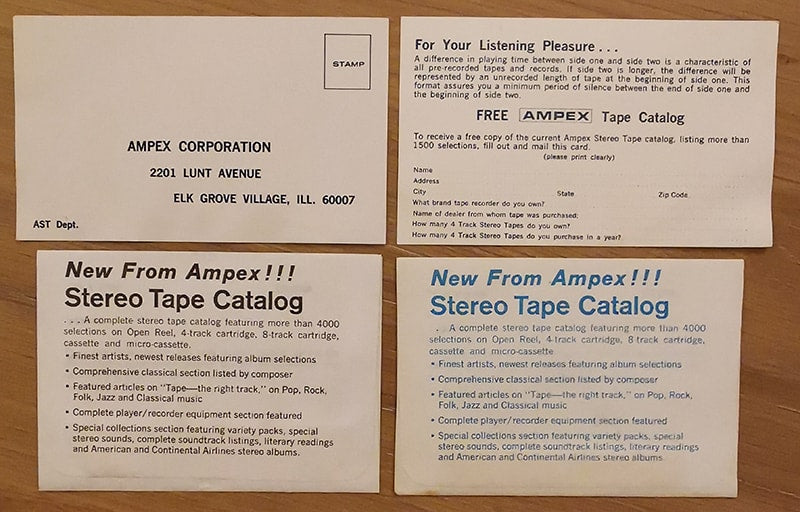

Starting with one of the generic information sheets, certain tapes duplicated on Ampex EX+ were accompanied by a small folder (of which both sides are seen here) that explained what the new formula offered. It discussed tape strength, durability against “nicking and tearing from careless handling,” and other life-extending virtues. I particularly loved the bit about “Ampex Ferro-Sheen®,” which sounds as much like a new type of condom as it does a tape type.

Both sides of the free 1-year subscription coupon for Tape Log which informed readers of new releases.

Various coupons for Ampex catalogs.

That’s the usual hype element for the casual consumer, though it is not as misleading as the missives declaring that 1/4-track was as good as 1/2-track, or how halving the speed didn’t have a deleterious effect. Pathological lying and undiluted bullsh*t are not modern concepts.

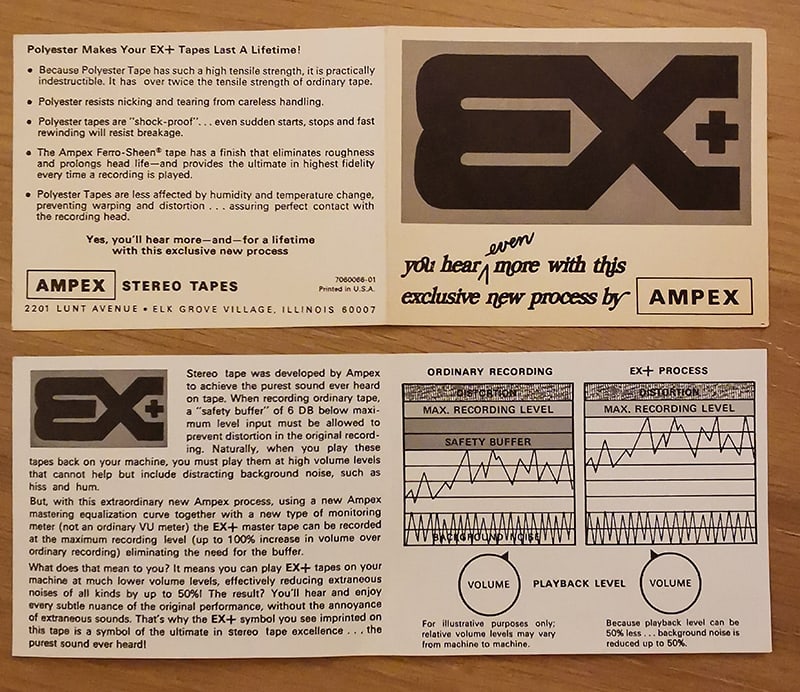

Of far greater value was the tech talk. Flip open to the center spread of the Ampex EX+ folder and the spiel changes from matters of tape longevity to sonic issues, i.e., how much they can load the tape. While Ampex drew the line at using terms like “headroom,” they did explain the relationship between recording levels and distortion, and then included a graphic to show this with a clear and comprehensible visual representation, free of jargon. How accurate it is may be a moot point, but the promise of enhanced performance probably was more than wishful thinking.

Insert explaining the technical virtues of Ampex’s EX+ tapes.

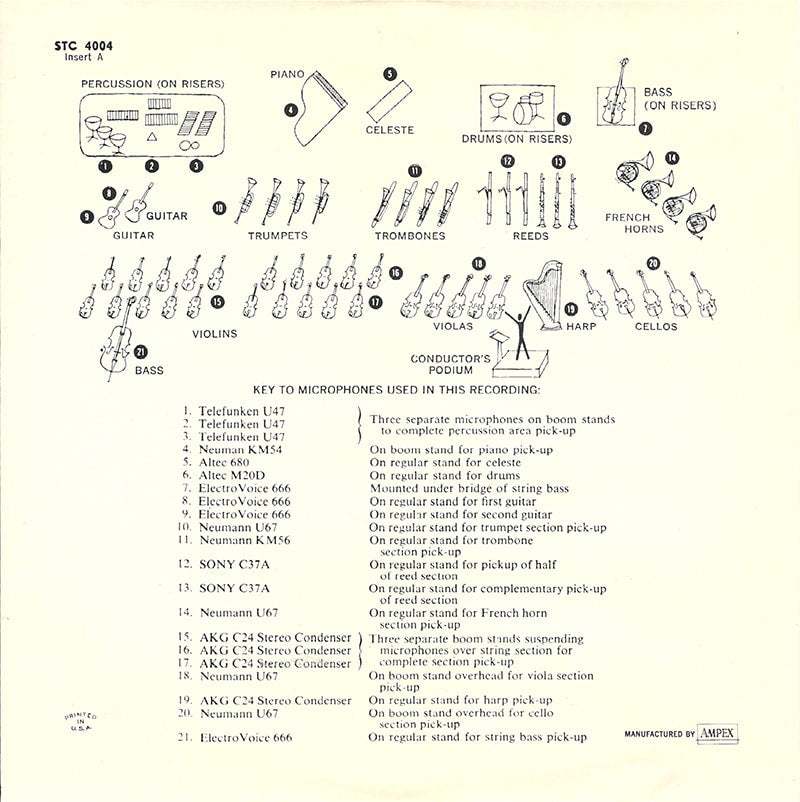

Even more informative were inserts related specifically to the recording in the box. I chose the one from David Rose’s 21 Channel Sound on MGM because it plays right into the desires of audiophiles who like to judge performance according to the soundstage. I recall how useful were Dave Wilson’s reviews back in the day when he wrote for The Abso!ute Sound, and recall trying to hear if the instruments matched his layouts.

MGM went all the way with the Rose tape because it was pushing multi-channel recording at the time: “21 microphones mean the ultimate in sound separation,” etc. OK, so with hindsight we also know that the cross-paired microphone technique might deliver greater realism, but commerce is commerce. Regardless of what you might feel about multi-track or multi-channel recordings, overdubs, or the like (and the finest recording I have ever heard used just a stereo pair – more about that in a future installment), the map of the orchestra with this tape is priceless.

Not only is every single instrument located on the sheet – all 62 or so musicians – every microphone is identified by manufacturer and model designation. Thus, if you’re a golden-eared studio denizen who can tell your Neumann U67 from your Telefunken U47, this sheet enables you to test your mettle. You will see, for example, that the two guitars were miked with ElectroVoice 666s, while the harp faced a stand-mounted AKG C24 stereo condenser. It just doesn’t get any better than this, and I have a few tapes with similarly extensive technical information.

David Rose and His Orchestra, 21 Channel Sound, cover.

David Rose, 21 Channel Sound, insert.

Does this make a difference to one’s listening pleasure? Ironically, the finest-sounding tape I have ever heard – a 1957 Josh White session from the Livingston Tape Library – has no technical information whatsoever. One’s ears tell the listener that there is a real space being reproduced, and oh, how nice it would be to compare it to a floor plan of the actual session. MGM’s 21 Channel Sound insert just makes me wish the Josh White recording was as well-documented.

By the way: the David Rose tape – with or without the insert – is sensational.