As time progressed, I added two more public access television shows to my resume. (See my previous article, “Public Access TV: A Perfect Soapbox” in Issue 160.) My newest show, Speak Out launched in the 1990s and had a viewer call-in format. My intention was for New Yorkers to comment (speak out) and voice their opinions on an assortment of issues. We had a wonderful time slot at 11 pm on Sunday night. The main competition was the 11 o’clock news and many viewers were channel surfing because they had already watched the earlier newscasts.

I invited guests who were in the news, or who had a public impact. That included but was not limited to elected officials, commissioners, and people from all branches of government. I would interview them and do some call-ins, and viewers would ask them questions. I never had anyone turn down an invitation to appear on Speak Out. The show quickly became the public access show of choice for New Yorkers.

I wanted to mix it up to keep everything spontaneous and within that framework, keep Speak Out relevant. If I had to go to an event or an onsite interview, those shows would be taped. I interviewed the lieutenant governor of New York State in his big office with an unbelievable view of New York Harbor. His office was on a high floor in the original World Trade Center. It was the last time I was in that building before the hijackers flew into the towers.

One of my guests was then-New York City Council member Anthony Weiner (aka Carlos Danger the disgraced Congressman) taking a telephone question from Abe Hirschfeld, the then-owner of the New York Post. Not everyone was from government. Curtis Sliwa of the Guardian Angels was on once, explaining what the Angels did and why New York needed them. All this was raw and unedited – anything we produced in the studio was live.

Another time I booked Congressman Jerry Nadler, and before the show we got to talking about the then-new mayor Rudy Giuliani (who was elected in 1994). Nadler told me that the new Giuliani administration had appointed my cousin Lee Sander to be the Commissioner of the Department of Transportation for New York City. It had not been announced yet, so you can imagine his surprise when I called him to wish him congratulations.

Rudy Giuliani was very accessible to me when he was a mayoral candidate, and again when he was elected mayor. We taped that second interview at his office in City Hall. I tried to touch all the angles and that sometimes resulted in some potentially dangerous shows. In one live broadcast the question of the night was, “are certain community leaders really helping their communities?” That got me a few death threats. On another segment I asked, “should doctors be allowed to assist in euthanasia?” It was a Jack Kevorkian-inspired show.

Rudy Giuliani and Ken Sander, 1990s.

Periodically we would have a change of pace. On one Speak Out episode I asked if viewers had complaints about their sexual partners. I had to use judgement with how I maintained my on-air persona. There were some shows, especially the ones where I asked questions about sex, where I did have some lighthearted fun with the callers. Maybe surprisingly, those shows never got calls from nasty people or other delete disrupters. Over time I saw a pattern develop: certain topics seemed to create more negative responses, such as asking questions about inequities that were racial, political or educational.

I received a surprising source of income from short clips from that show, which earned me about $5,000 or more. The BBC bought most of them for a documentary on unusual television shows from around the world. All three of my public access shows, The Cable Doctor, Speak Out and Open Door were aired during the 1990s. I made some nice money selling video clips for foreign documentaries. Every sale of a clip could pay significant dividends down the road, usually about 50 percent of the initial fee to reuse them on reruns. There was never a problem collecting the money; although the checks came at unexpected intervals, the foreign television companies were diligent about honoring their contracts and keeping track of the airings. Between German and British television, I took in about $40,000 in broadcasting fees.

Speak Out’s studio had four on-air phone lines, and they would blink when a call came in. so I always knew if I had calls waiting. There was no seven-second delay (in industry terms, a “deferred live” or “profanity delay”) like those for live commercial network radio and television. That seven-second delay would allow enough time to delete any profanity or attempted disruption before it got on the air. Speak Out didn’t have the benefit of that delay, and a disrupter would sometimes get through. These callers were like a naked streaker at a sporting event. An annoyance to all with for no purpose for anyone. Those disrupters were annoying but I refused to be provoked.

I needed some help so at the end of some of the shows I would ask for volunteers. I soon found that there were viewers who wanted to help with the production of the show; volunteers who just wanted to be part of the action. I always got a good response and had some great folks who worked on the show with me. One would answer the phones and ask the callers what their question was (which would help screen any potential problem callers). Then, the callers were put on hold, and I would answer them in order. Sometimes I had professional camera operators who volunteered to do remote spots for Speak Out. Most of them worked for various local network news shows as back-up camera and sound technicians.

I took many of the questions from current headlines. The more controversial and timelier the subject, the better the interest level from the audience. An example would be the time a transit authority worker was on his way home to Brooklyn. He had just gotten off the subway. Two teenagers tried to rob him at gunpoint. He pulled his gun and shot them both dead. Self-defense? One might think so, but the responding police officers observed that the teenager’s guns were toys. To further cloud the issue, the gun used by the intended victim was unlicensed, thus making it illegal. This was a dilemma. A working-class man killing two teens who were attempting to hold him up with toy guns. Of course, the intended victim had not known that the guns were toys.

One can imagine the headlines in the New York tabloids. And it raised questions. Should this man be charged with carrying an illegal handgun? Did he commit a crime? Even if he had applied for a gun permit, would he have received one? He lived in a dangerous neighborhood and often had to walk home through an empty park late at night, certainly not a comfortable stroll. There were many different angles to this sad story.

New York City has some of the strictest gun laws in the nation. The Sullivan Act, passed in 1911, made it a felony to be caught with an unlicensed gun on the streets of New York. It is incredibly hard for an average citizen to get a gun license in New York, especially a license to carry, or CCW. One had to demonstrate that there was a necessity for self-protection, such as being a business owner who handled large amounts of cash. Certain security people were carefully vetted and sometimes, famous and wealthy people could get a CCW. The usual sentence for carrying an illegal gun was one to two years, with most convicted offenders serving at least nine months and that was for possession only, without the perpetuation of a crime.

You know where I am going with this. This was a Speak Out question made to order. That Sunday night we poised the question: what was your opinion of the situation? Know this: the point of the show was to ask the questions and not for me to have an opinion or take sides. It was up to the viewers to air their opinions.

The show started and the phone lines lit up. At that point I had over a hundred live shows under my belt. I understood that on live television anything can happen, and I was ready. (One time a man walked into the studio asking the cameraman and then the show’s host for spare change. That show was broadcasting live at the time, and you can imagine the frantic scene in the studio.)

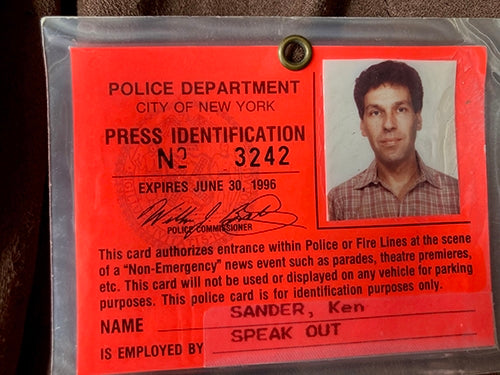

Ken’s New York City press pass, 1990s.

There was a pattern. Most of the antagonists would start with their question or comment, and then go off on a tangent. In the case of this segment, it started with something like this: “Hi Ken, do you think the teens or the transit worker were at fault? F*ck you, you son of a b*tch!” The disrupters were usually just a small minority, but that night I’d hit the mother lode of abusive viewers.

Nothing fazed me; this was no-holds-barred television. I had developed techniques to deal with disruptive people. Seemingly every show had one weird caller, and experience had taught me early on not to react on the air. I certainly would not give them the satisfaction because if I had any reaction, the abusive calls would increase.

In addition to never reacting, I had another technique for ditching callers. If a caller turned abusive, I quickly disconnected them. While doing so, I either answered the first part of their question, or made another, unrelated comment based on the subject matter of the show. I was very quick with the disconnecting and nobody caught onto what I was doing: “Hi Ken, who do you think the real victim is? Fu…” that was all they got out of their mouth before they heard the dial tone. Unfazed, I would go to the next call. Time on air goes fast, and in spite of the flood of prank callers, there were some good questions and comments from thoughtful viewers.

My phone guy Barry said that was a tough show. I answered, yes, it was. In fact, that was the most difficult show I had done to date and I wondered if this was the beginning of a new trend. I took note, and the next week’s show was back to normal, so I felt that that one show was an isolated incident.

I thought no more about it.

A few months later there was a message on my answering machine. The caller had said, “Hey Ken, make sure to watch The David Letterman Show tonight. I am sure you will find it interesting.”

David introduced a segment by saying he and Paul (Shaffer) were wondering what their television careers would look like in 20 years. They panned to a studio with Dave by a telephone. Paul was screening calls. The callers would get by Paul and be connected to David, and would exclaim, “Hi David, you suck!”

Years passed and I was working for Penthouse magazine as a consumer electronics journalist, writing a monthly column called “Technomania.” One day in 2007, out of the blue someone e-mailed me a YouTube link to that Speak Out show about the shooting. For the first time ever, I watched it.

Over 10 years had passed since the initial airing, and I wondered where that YouTube video had come from. Had someone taped it off the air? (I am fairly sure I still have the original 3/4-inch U-matic master. So far, this mystery is unsolved.)

Within a week the segment was all over YouTube in various versions, not all of them flattering. Most versions had edited out the legit comments and just showed the obnoxious calls. Many of these YouTube clips were different lengths, the result of edits from unknown origins. Weird – but the show had acquired a totally new viewership! One posting was even selling copies of the show through Amazon.

(The David Letterman segment begins around 5:40 into the video.)

Now, another 15 years have passed, and the clip is still on YouTube. To this day I get occasional e-mails and inquiries about it including requests for autographed pictures, and people who want to contact me. Occasionally, a phone call gets through.

Looking back, I see that it was a test of my on-air abilities and a baptism under fire. At the time when it first aired, I thought it was just another Speak Out show.

People ask me if I was upset with these calls, and no, I was not. None of my other shows had ever produced that many disruptive calls, but that segment was gonzo television. This came with the territory, part of the deal so to speak. Sure, I would have preferred a show that had gone as I envisioned, but that is not what happened. I was in the moment, and I never took the calls personally. It was like being yelled at by an irrational person, not pleasant but not of any consequence either. If I gave the disrupters any thought, it was that they were inconsequential, certainly not anyone of merit.

I never saw that level of disruption coming, but no matter, I dealt with it.

Really, enough said.