When it comes to live albums, many music fans have a wide variety of personal favorites. A large cross-section of top choices would likely include recordings from David Bowie, Jackson Browne, Neil Young, Bruce Springsteen, Eagles, George Benson, Frank Sinatra, Jaco Pastorius, Aerosmith, Eric Clapton, Prince, the Rolling Stones, the Roots, Hall and Oates, Pink Floyd, The Boston Pops, Willie Nelson, KISS, Michael Bublé, Harry Connick Jr., Pearl Jam, The Three Tenors, and countless others. The aforementioned all have something in common: their live releases all had engineering help from David W. Hewitt.

Launching his career during the early 1970s at Regent Sound Studios in Philadelphia and then the Record Plant recording studio in New York, Hewitt was one of the foremost pioneers in designing remote multitrack recording studios and putting them into practice, with thousands of concert recordings from hundreds of artists all across the United States and abroad. His innovative work in bringing state-of-the-art recording technology to the mobile truck led to Hewitt being constantly in demand by top artists in the music industry over the last half-century, capturing their historic concert performances for posterity and live releases.

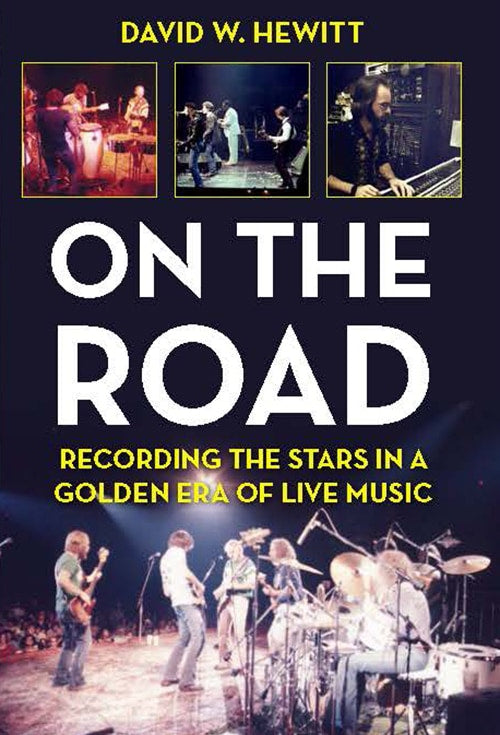

On The Road: Recording The Stars in a Golden Era of Live Music is a memoir/diary of that era, with stories that draw from a huge list of famous and even legendary concerts. Told from the ultimate insider’s perspective, On The Road recounts Hewitt’s involvement to preserve those moments in musical history.

Although On The Road can be considered an autobiography of sorts, David W. Hewitt is impressively humble about his many accomplishments and contributions to the industry, describing such historic events as his recording involvement with Live Aid, Eric Clapton’s Crossroads concerts, the No Nukes concerts, the post-9/11 The Concert for New York City, and other landmark performances from a fan’s perspective, rather than that of the consummate professional engineering specialist that made these concerts available to the millions who could not attend.

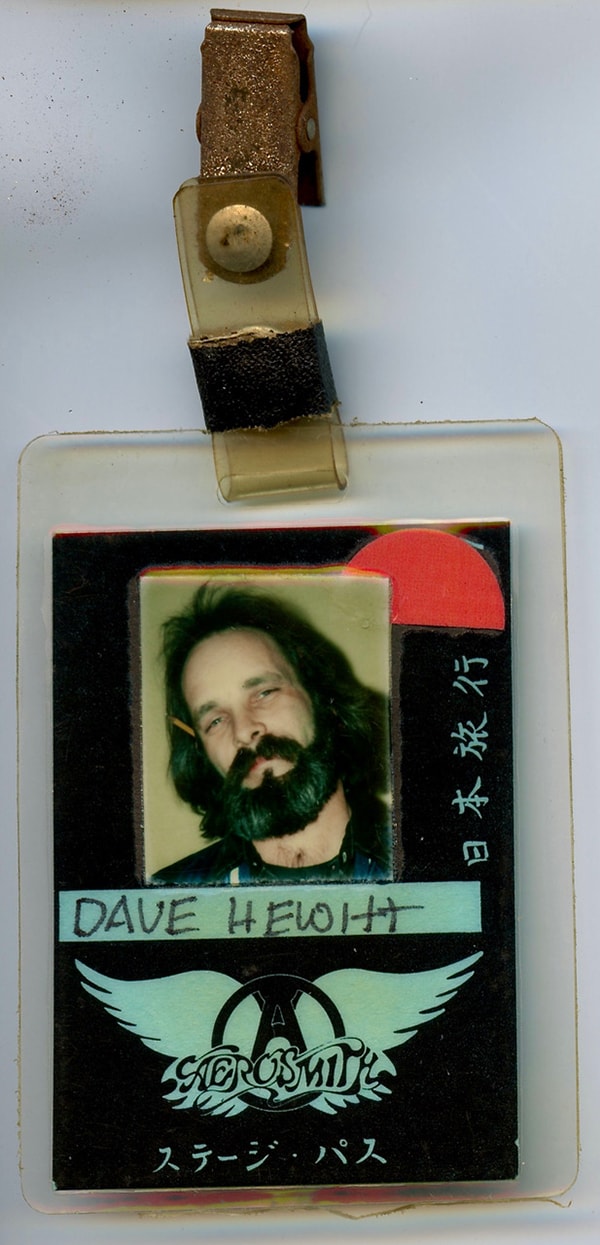

David W. Hewitt’s Aerosmith backstage pass. Courtesy of David W. Hewitt.

Hewitt’s behind the scenes account of the 1979 Havana Jam illustrates some of his “fan” mindset. He was wowed by Stephen Stills’ performance with Bonnie Bramlett and Mike Finnegan doing the Nash and Crosby parts for Crosby, Stills and Nash songs; the one-time only live performance of The Trio of Doom (Tony Williams, Jaco Pastorius, and John McLaughlin), a legendary, short lived ensemble whose only recording was not released until nearly 30 years later; and Billy Joel, whom Hewitt had recorded multiple times in the past, and whose show in Cuba was, in Hewitt’s view, “one of his best performances ever.”

Hewitt sadly recounted that he had been ordered by Joel’s production staff to make sure that his performance would not be recorded, so the magic of that night is one of few that Hewitt can confirm only exists in memory.

Additionally, he also recalled that due to Cuba’s strict Communist surveillance and control over any visitors, their assigned government “minder,” from whom they got separated during the concerts, frantically ran up to them at the airport restaurant before they boarded, crying, “Thank God I found you! If I lost you I would have been arrested!”

Billy Joel, Live at Yankee Stadium, album cover.

Early in the book, Hewitt amusingly described his serendipitous live recording beginnings in 1973 as a remote-recording engineer: being “hijacked” by Frank Hubach, who was in charge of the Record Plant’s then-new mobile recording department, because Hewitt was one of the few qualified assistant engineers at the time with any road experience. This first live remote gig for Hewitt turned out to be for the D.I.R. Radio Network’s King Biscuit Flower Hour show, an eclectic radio program featuring recorded live concerts from a huge mix of musical artists. The headlining artist was jazz-rock fusion avatars the Mahavishnu Orchestra and the opening act was none other than Aerosmith, who would become longtime friends and clients of Hewitt in decades to follow. The Aerosmith relationship with the Record Plant, due primarily to producer/engineer Jack Douglas, resulted in Hewitt providing the remote truck at Aerosmith’s rehearsal warehouse for the recording of the albums Rocks (1976), and The Cenacle estate for Draw the Line (1977), and numerous other live concert recordings at the Boston Garden and other venues.

The King Biscuit recordings, and TV programs featuring live performances such as The Midnight Special and In Concert, caused the demand for remote recording capabilities to explode, as consumers demonstrated an appetite for recorded live music that extended far beyond Woodstock in 1969. No longer merely a revenue platform for ticket sales, concerts became a valuable revenue source for record companies as live recordings began to proliferate and go gold or even platinum.

With the Record Plant in New York evolving to become one of the premier recording facilities in the US, Hewitt kept assiduously up to date on the latest and most in-demand equipment required for professional multitrack recording projects. As the artists began to demand the same level of quality in their live recordings as in their studio albums, Hewitt helped modernize the aging “White Truck” they had been using and designed the new-generation Black Remote Truck. Now the powerful modern diesel Peterbilt and heavily-isolated recording studio could easily travel the entire country without strain. Custom power and audio cabling systems allowed faster load in and out even at the most difficult locations. As he gathered and trained full time crew members, the remote business grew rapidly. It became a major player around the country.

Combined with an indefatigable work ethic (when he was injured in a 1989 crash that destroyed one of his remote trucks, Hewitt’s concern over getting a replacement remote recording truck to fulfill a Harry Connick Jr. concert contract took precedence over notifying his family of the accident) and a quick, problem-solving attitude honed by his earlier experience as a member of a pit stop crew for professional sports car races. Hewitt’s innovative customizations to the Record Plant “White” and “Black” trucks led to his becoming one of the music industry’s most in-demand remote recording engineers.

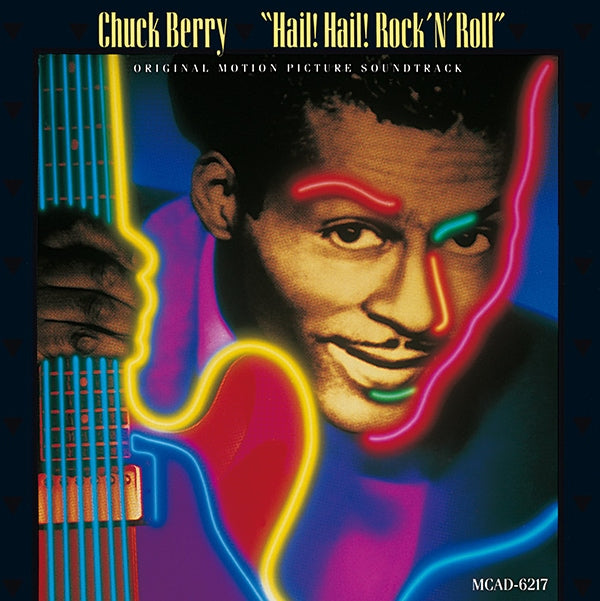

The trust that developed between Hewitt and superstar artists like Neil Young, for example, extended to film and video projects, such as Rust Never Sleeps (1979), Neil Young Red Rocks Live (2000), and the Jonathan Demme-directed Neil Young: Heart of Gold (2006). Hewitt would become the first-call remote recording truck specialist and engineer for concert documentaries like the Taylor Hackford-directed Chuck Berry tribute, Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll (1987), U2’s Rattle and Hum (1988, directed by Phil Joanou), Martin Scorcese’s Rolling Stones concert film, Shine A Light (2008), and others.

There is hardly any major concert event between 1975 and 2015 in which David W. Hewitt or his company’s remote recording trucks were not involved. In addition to talking about the recording and production of televised awards shows like the Academy Awards, Tonys, Grammys, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Country Music Awards and others, he devotes an entire chapter of On The Road to what he has dubbed “The Monster Shows,” which include:

- No Nukes: The MUSE Concerts for a Non-Nuclear Future (Madison Square Garden, five days, 1979)

- Night of 100 Stars (Radio City Music Hall, five days each, 1982 and 1985)

- Live Aid (JFK Stadium, four days, 1985)

- Atlantic Records 40th Anniversary (MSG, four days, 1988)

- Bob Dylan’s 30th Anniversary concert (MSG, three days, 1992)

- Woodstock ’94 (Saugerties, NY, seven days, 1994)

- Woodstock ’99 (Rome, NY, four days, 1999)

- Super Bowl 1996, 1997, and 2009

Woodstock ’99, album cover.

Additionally, Hewitt devotes an entire chapter to his lengthy body of work with Eric Clapton, which included providing remote trucks for all of the Crossroads festivals, the Cream reunion concerts, and other releases, starting with the live album E.C. Was Here (1975).

The insights and behind the scenes first-hand observations that Hewitt cites about these landmark concerts are well worth the read for any music history buff. Meticulous about technical details, he also includes comments from colleagues and other crew members. For example:

- David Brown explains that during the pre-computer-memory analog days of recording the No Nukes concerts, there were several big-name engineers, such as Shelly Yakus and Jimmy Iovine, who wanted to save their respective EQ settings for different bands – all on the same remote console. This was accomplished by the extremely dangerous process of “hot swapping” API equalizer modules while the power was still on, which Brown describes as “the electronic equivalent of changing a wheel on your car while it’s driving on the highway.”

- The anticipation for Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band’s set was so strong that the crowd’s unison chants of “Bruce!” combined with foot stomps actually shook the fifth-floor concrete slabs of Madison Square Garden up and down almost two inches, resulting in the 400-plus pound Ampex 1200 multitrack machines shaking in the truck. An assistant had to use his body as a wedge to keep them in place while the tape was running!

Although rock, R&B, and country music get the bulk of coverage in On The Road because these genres comprised the largest chunk of Hewitt’s projects, classical music and jazz are also documented, with insights into classical music concerts by Yo-Yo Ma, Beverly Sills, Isaac Stern, Virgil Fox, Kathleen Battle, Luciano Pavarotti, Andrea Bocelli, and many others, as well as jazz from Dave Brubeck, Diana Krall, Hugh Masekela, George Benson, and more.

On the Road also offers a special, heartfelt section on Hewitt’s reminiscences and contributions to The Concert for New York City at Madison Square Garden on October 20, 2001, a month after the tragic attack on the World Trade Center.

Chock full of anecdotes and interspersed with technical comments filtered through the purview of a truly dedicated music fan, David W. Hewitt’s On The Road is a fascinating read that gives many fly-on-the-wall glimpses into a panoply of iconic musical events.

******

An in-depth interview with David W. Hewitt will be appearing in forthcoming issues of Copper. For now, here’s a sample:

John Seetoo: You have recorded countless historic concerts that have been released as recordings (Rust Never Sleeps), broadcast on radio programs (The King Biscuit Flower Hour), on television (MTV Unplugged), and in films (Hail! Hail! Rock n’ Roll). Can you compare the differences in the demands on your work by the artists and producers for each of these mediums, and recount some of the unusual workarounds you had to devise to both keep everyone happy and ensure that the final product met your personal standards?

David W. Hewitt: Neil Young’s Rust Never Sleeps 1978 tour [resulted in] one of my all-time favorite recordings. Neil and his long-time crew had it together for a cross country run from Boston to San Francisco. Long tours require advance work for all the travel routes, permits, flights, hotels, etc. and coordination with the band crew, sound, lighting and production crews and so on]. It changes every day and every gig. [Some] stories are in Chapter seven in my book.

The old tour motto is, “the show is that little inconvenience between the load in and the load out.”

There can be dramatic differences in our “mission,” [beginning with], “who is the client?”

[Let’s talk about] radio. For many years we recorded shows for later live radio broadcasts: King Biscuit Flower Hour, the RKO Radio Network, the ABC Radio Network and live local stations WPLJ, WNYC, and my favorite jazz radio station, WBGO! I always loved radio, from [my] childhood in Montana to a lifetime of travel worldwide.

My first remote recording for the Record Plant in New York was for King Biscuit; it was also their first show! Snowbound in Buffalo, New York…the fusion Band Mahavishnu Orchestra was absolutely brilliant, with some rock band called Aerosmith opening for them. The crowd went wild! Then, [there was] another show back in New York, where a guy named Bruce was opening for a folk singer at Max’s Kansas City. It was Bruce Springsteen. This show started the many successful years of King Biscuit’s Sunday radio program, until, like the song, video killed the Radio Star.

Of course, film and live TV had long been showing bands, but now with stereo radio simulcasts making mono TV obsolete, it had to change. Movie theaters had a head start on large sound systems, and now touring gear made for great feature film sound like the Chuck Berry documentary Hail! Hail! Rock n’ Roll.

Hail! Hail! Rock ‘N’ Roll, original motion picture soundtrack album cover.

Now this is a long story, best read in the book, but the short version is that Keith Richards, Eric Clapton and a host of stars produced incredible shows [that were] filmed by director Taylor Hackford. Chuck Berry was a hero to Keith and so many of the British musicians as they learned the history of the blues. And boy did Keith pay Chuck back, with such dedication, and patiently playing whatever Chuck decided to play.

We recorded at Chuck’s old club in St. Louis, Missouri, his studio at Berry Farm (his home), and the historic Fox Theatre in Atlanta. We were joined by the great engineer/producer Michael Frondelli, who would follow the project through. This is one monumental film, made while Chuck Berry was still Chuck Berry!

My recording career started out in the studio, recording musicians for records and the occasional film soundtrack. When I accidentally landed in a remote truck, that all changed. Suddenly these people with cameras started showing up needing odd sync signals and time code. WTF was that?

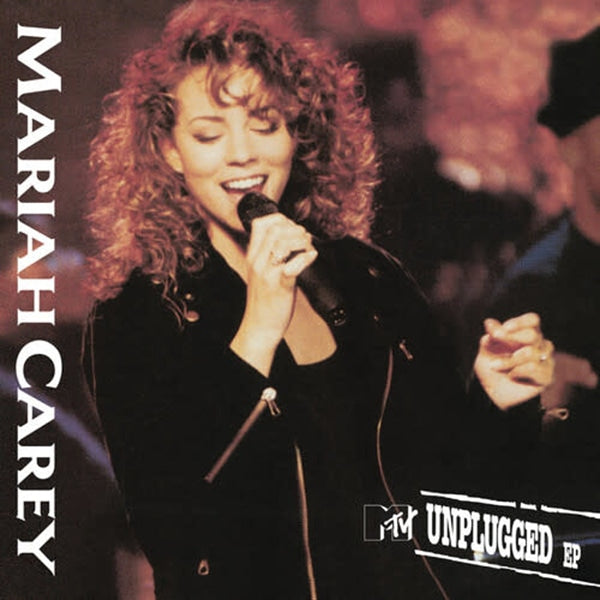

With MTV Unplugged, well, they unplugged some of the musicians’ instruments, but the [plugging in] always seemed to find a way back. The show that really made MTV Unplugged a success was the 1992 Mariah Carey episode. I had recorded Mariah starting with the first show [that] Tommy Mottola, then head of Sony Music, produced for her debut. After several successful studio albums, she still was shy of live performances. This early MTV Unplugged live performance became a surprise hit, going multi-platinum around the world. Certainly helped my engineering career as well! I recorded Pearl Jam on that same gig. Nirvana and many others followed.

Mariah Carey, MTV Unplugged, album cover.

My favorite “unplugged” recording was the incredible 1997 MTV concert for Babyface with Eric Clapton playing. Now go listen to them play “Change the World” and you will hear what I mean.