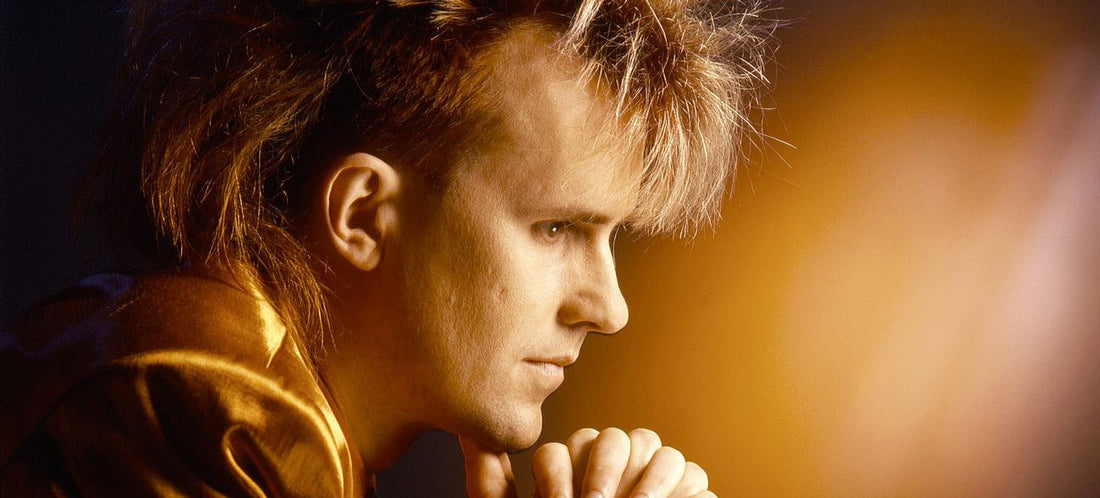

Just a scrawny English kid with spiky hair, a bunch of synthesizers, and chipper lyrics? Or is there more to Howard Jones? I would argue that there is. For one thing, he’s got longevity. Although in the ʼ80s people might have pegged him as a flash in the pan, in May 2019 he released his 13th studio album. That alone is worth some respect.

His childhood and teen years were spent in Wales, England, and Canada. He wasn’t a piano prodigy, just a talented, musically adventurous kid. In his teens he had a close friend who followed Buddhism, which influenced his songwriting; Jones eventually became Buddhist himself, and the philosophy of peace, positivity, and absence of self has always informed his lyrics. Heard through a radio in the 1980s, his songs may have sounded goofily cheerful, but a closer listen reveals a deeper world view.

And then there was the day in 1979 when his girlfriend bought him a synthesizer, and the store accidentally delivered two. Jones set them both up, and immediately fell in love with the options provided by having multiple keyboards. (He insists he did pay for the second one.) By 1983, he’d perfected his unusual sound enough to convince Warner Music Group to sign him.

The Warner execs knew what was just over the horizon in pop: lots of high-energy synths and a slightly space-alien look. Jones’ husky voice, with a large range and no vibrato, also fit right into the billowing New Wave, as did the simple fact that he was British and sported a working-man’s accent.

Warner released the single “New Song” in advance of Jones’ first album, Human’s Lib (1984). The UK and US were charmed by the bouncy song and its MTV video (still a novelty to many people). But the US didn’t get the best single.

Probably Jones’ strangest song is a mesmerizing riddle called “Hide and Seek,” a dark vignette about primordial Earth and first humans. It was (surprisingly) a hit in the UK, but album-only in the US. For most Americans, Jones’ appearance at Live Aid in 1985 was the first time they heard this song, but the British crowd at Wembley knew it well enough to sing along on the chorus. The fact that this spooky fantastica got radio time is testament to how, from the start of his career, Jones’ ability to write catchy refrains has actually prevented people from listening closely to his words.

Top-40 fans were so busy bopping around to Jones’ beat that they missed the intricacies of his compositions and arrangements for synthesizer. He was truly innovative in his use of layered samples and textures to form a three-dimensional sound world. Maybe his skill is more obvious from our current vantage point, when we listen to so much through headphones and therefore catch more details. In any case, “Automaton” from Dream into Action (1985) is an impressive rhythmic structure:

There’s no point in pretending that Jones’ catalog will prove an endless treasure trove for rock fans. After the first two albums, his output weakened for a few years. The 1986 release One to One 1986 has nothing new to offer. Except for the delightful “Everlasting Love” and the intriguing “The Prisoner” (about how some cultures believe photographs steal your soul), Cross That Line (1989) is relentlessly New Age-y.

But things get more interesting if you persevere. Check out In the Running (1992). One of the things it has going for it is the collaboration with guitarist Steve Farris, at the time best known as a member of the band Mr. Mister. The legit rock guitar solos on tracks like “Exodus” give Jones’ arrangements more substance and wider appeal.

R&B has always influenced Jones’ work, but it’s especially obvious on the 1994 album Working in the Backroom. “Don’t Get Me Wrong” is sort of a deconstruction of R&B tropes. The scant three lines of lyrics repeat, riding on a funk-driven hook that disappears and then returns over and over, eventually to stay and grow, and finally to dissipate into an ocean of synth sound.

With Working in the Backroom, Jones also inaugurated his indie record label, Dtox. He did it the hard way, dragging crates of CDs with him to gigs. This was before the internet offered efficient means of connecting fans to new music. People (1998), the next Dtox album, had originally been released in Japan as Angels & Lovers. To support the album, Jones made the savvy decision to jump into the embryonic ʼ80s nostalgia industry (a business that is now at full-throttle, of course), by touring with Culture Club and Human League.

“You’re the Buddha” lays out Jones’ (and listener’s) search for meaning in a word-packed lyric that edges near rap. The laid-back funk rhythm, the brass chorus, and the female back-up singers give the synths something substantive to contend with.

The self-exploration continues on Revolution of the Heart (2005), whose tracks tend toward massive waves of sound. “The Presence of Other” is typical of the album’s other-worldly sound

Jones’ most recent album is Transform (2019). It’s retro in a way, returning to more of a high-energy ʼ80s synth-centered sound. But the musical and lyrical sophistication are colored by Jones’ age (64) and experience. “Tin Man Song” has a minor-key jazz vibe, more Sade than A Flock of Seagulls. And the words betray a pensive soul, far more serious than that spiky-haired kid seemed in the ʼ80s: “I want to hear the nightingale / Ponder the horizon / I need to dream of distant stars / And marvel at creation.”

If you’re curious enough now to check out the constantly touring Jones, I can attest that he puts on a good show. He’s a pleasant raconteur, as comfortable playing in a big hall as he is in a small club. And if you’re lucky, you’ll get to see him do an acoustic duo set with guitarist Robin Boult.

Header image courtesy of Simon Fowler/howardjones.com.