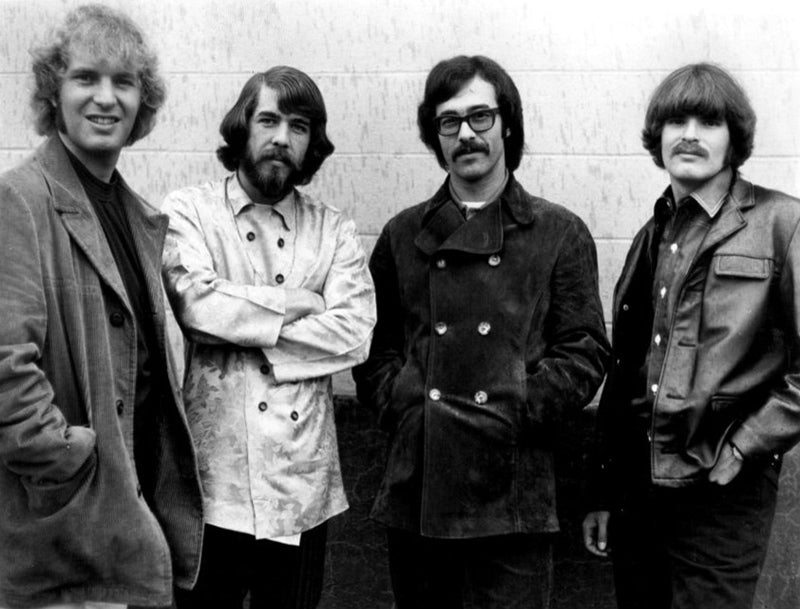

They’re known for singing about the bayou with a Louisiana twang, but the members of Creedence Clearwater Revival all came from a suburb of San Francisco. But that’s showbiz, and these guys sure could put on a show.

As fellow students at their junior high school in El Cerrito, singer/songwriter John Fogerty, drummer Doug Clifford, and bass player Stu Cook formed the Blue Velvets in 1959. Fogerty’s older brother, Tom, was already a gigging guitarist and singer himself, and he joined the Blue Velvets as they started to gain traction, getting radio play with a few singles. They signed with Fantasy Records in 1964, where they were forced to rebrand as The Golliwogs, after a racially problematic character in children’s books. That move never sat well with the band, and thanks to new ownership at Fantasy in 1968, they were able to adopt the name Creedence Clearwater Revival, inspired both by a beer commercial and a friend’s unusual first name. Although it was primarily a jazz label, Fantasy remained CCR’s label throughout their short but spectacular run.

By this point, the band was ready to release its first album. During the preceding couple of years, John Fogerty had put in a lot of work to get a handle on a number of instruments, including saxophone and harmonica, which would help establish CCR’s distinctive sound. It was also agreed that he had the best voice, so he became the group’s lead singer. To further establish his leadership, he produced their full-length debut, Creedence Clearwater Revival (1968).

On the album were several songs by Fogerty, two of which they had previously recorded as the Golliwogs, plus three covers: Dale Hawkins’ rockabilly song “Suzie Q,” which did well as a single; Wilson Pickett’s “Ninety-Nine and a Half Won’t Do”; and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ “I Put a Spell on You.” The band was proving its facility with these old, blues-based southern styles.

The most significant difference between the debut album and Bayou Country (1969), is that John Fogerty wrote the second record almost entirely by himself. This, along with his always singing lead and producing, was already starting to grate on the other bandmembers. However, there was no arguing that it was commercially the right move. The single “Proud Mary” comes from this album.

The band also solidified its signature “swamp rock” sound – the members’ personal backgrounds notwithstanding – on tracks like “Born on the Bayou.” That’s thanks to the loose, jangly guitar, the sizzling backbeat, the insistent chords in a lazy tempo, Fogerty’s rasping voice and drawl, and of course the underlying blues harmony.

Another record, Green River, followed a few months later, yielding the title single plus the mega-hit “Bad Moon Rising.” Fogerty has described how he was getting the hang of writing semi-autobiographical stories, but relocating them to settings not actually connected with his life to give them a fictional feel. A good example is the song “Lodi,” which talks from the heart about how tough it is getting a music career off the ground but takes place in a California town that Fogerty had never even visited.

He was also getting more imaginative at integrating his own experiences into made-up characters’ adventures. The Johnny Cash-inspired “Cross Tie Walker” is one such narrative. With Cash, that lonesome hobo’s tale would have been straight out of his own wanderings, but with Fogerty, it’s just a metaphor for more general troubles in his life. The crunching texture and dotted rhythm in the bass bring the genre reference to life.

Given the short time that CCR was together, fans can be grateful that Fogerty and company were remarkably prolific. Willy and the Poor Boys was their third album of 1969. And their quality in no way diminished with their increased quantity. This record included two more rock classics: “Down on the Corner” and “Fortunate Son.” It’s notable that these two celebrated songs were back-to-back on one single, with the latter as the B-side.

The album’s title referred to the original concept: the idea was to tell a collection of stories relating to a fictional jug band called Willy and the Poor Boys. Although the title stuck, the concept fell away during recording sessions, where other themes arose. One was a love of blues legend Lead Belly, demonstrated in the folk songs “Cotton Fields” and “Midnight Special.” The first of those made CCR a top seller in Mexico. Among the album’s new songs, “Fortunate Son” is one of two anti-Nixon statements. The other is “Effigy,” which closes Side Two.

The band’s popularity just would not budge. Cosmo’s Factory (1970) spent nine weeks as the number-one album in the US. From it came the hit singles “Looking Out My Back Door,” “Travelin’ Band,” and “Who’ll Stop the Rain.” The first of these was in part a tribute to Buck Owens (who is mentioned in the lyrics), inventor of the so-called Bakersfield Sound, a style that fused rock rhythm into country music.

For this record, CCR included some R&B, such as their cover of “I Heard It through the Grapevine.” They also dipped their toes into the psychedelic world with “Ramble Tamble.” But even amid the long, winding instrumental solos, there’s still a Southern rock core.

Pendulum (1970) was the source for another cherished classic single, “Have You Ever Seen the Rain.” This album is all about orchestration: Fogerty played multiple tracks of saxophone, providing a sonic density that doesn’t occur on the earlier records. He and Cook also piled on the piano and Fender Rhodes parts, and all four men played percussion instruments to contribute more texture to the arrangements.

The keyboard and sax lines, as well as vocal harmonization, are particularly interesting on “Sailor’s Lament.” The short, repetitive melody gives the song almost a reggae flavor.

CCR’s final album was Mardi Gras (1972). There was an uncharacteristic two-year gap after Pendulum. Tom Fogerty had quit, and the other three men weren’t getting along, so it was a struggle to decide to get back into the studio to begin with. Once there, they had to adjust to being a trio, and the creative differences flared up worse than ever. They never toured in support of this album but broke up as soon as it was released.

While commercially and critically a flop, the record is a curiosity for giving Cook and Clifford more participation as composers and singers. The song “Tearin’ Up the Country” was written by Clifford and features his voice instead of Fogerty’s. Quite a different sound!

Tom Fogerty died in 1990. Cook and Clifford continued to work together on various projects, including a CCR touring show, Creedence Clearwater Revisited, although John Fogerty tried to stop them from using that name. As for Fogerty, he became a highly successful solo artist, with hits like “Centerfield” and “The Old Man Down the Road.”

The members of CCR never did recover from their jealousy and legal in-fighting. When they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993, Fogerty would not allow Clifford and Cook onstage to perform with him. So, don’t expect a reunion. But the wonderful thing about living in the age of recorded sound is that we will have CCR’s music forever, even though the group only lasted for a few years.