In the 1950s, TV sets had lousy pictures – but some of them had rather good sound. Our 16-inch RCA TV (“that big screen in a 12 x 12-foot room?” said the neighbors; “you’ll go blind!”) showed images only in black and white, of course, with a 525-line vertical resolution (up to 486 of those lines visible) and about 440 pixels horizontally – about one-tenth the resolution of a 1080p digital TV. But the RCA had a wood, floor-standing cabinet, with an 8-inch speaker baffled on all sides except the back. Since all else we had were two Emerson AM radios, it had the best sound in the house.

And our TV had an audio input jack on the rear panel – RCA’s way of encouraging sales of the Victrola Attachment 45 rpm record changer, the company’s answer to the LP system Columbia Records had introduced a year or two before.

Aged 11, I’d been listening to our AM radios, largely to classical music from distant New York City. But with one of those little changers and some records, I could hear music of my choice whenever I wanted to. And, at $12.95 (including six records!) I could afford it from banked birthday money my parents hadn’t let me spend. I got Dad to break $25 loose from my savings account, and scampered down to Conn’s Record Shop on Church Street.

And what a haul! The RCA player, of course, plus Mario Lanza’s Great Caruso album (I wanted to sing like that tenor back then, though still a soprano at the time), a single by Caruso himself, one Spike Jones single, three Phil Harris discs, and another record or two that I’ve forgotten.

I wasn’t an audiophile yet, but I had two audiophile traits – a love of music and the urge to make improvements. The first one, at my urging but on Dad’s nickel, was to replace the 45-only changer with a Webcor 3-speed model, so we could play LPs, too. The second, once I’d been introduced to hi-fi by my high school chem teacher, was to replace the TV’s 8-inch driver with a $10 Lafayette SK-98 whose cone had a hardened center section for better highs. (I’ve heard since that it was made by Pioneer.) Rated response was “40 – 16,000 cycles per second,” numbers that meant nothing to me at the time.

That sufficed until I went off to Yale, and had to leave our TV console home. I bought a small, $15 ported enclosure from Lafayette, and a used Realistic 10- or 12-watt amplifier (built by Grommes) for $10 from my girlfriend’s father. I progressed from there to a used 25-watt Heathkit W5M amp and model WA-P2 preamp that took its power from an octal socket on the amp. The preamp’s main feature was selectable turnover and rolloff frequencies, to deal with the many company-specific record-equalization curves then prevalent; the RIAA curve was already in use, but there were still a lot of older discs out there. (Unfortunately, I couldn’t use that selectable EQ, because the Webcor had a ceramic cartridge that didn’t require equalization.) I also moved the Lafayette speaker to an RJ enclosure that I got cheap because the foam surround of the RJ’s original Wharfedale driver had rotted out.

Heathkit WA-P2 preamplifier.

Sophomore year, I roomed with guys who wanted something fancier, and in new-fangled stereo. Rather than pool our money for a jointly-owned system we’d have to sell off when we went our separate ways, we each bought one system component. I don’t recall what speakers we wound up with (AR-1s?), but I know we had a sleek-looking Fairchild arm, cartridge, and belt-drive turntable, plus an H.H. Scott stereo preamp and H.H. Scott 330 “binaural” tuner. The 330 had independent AM and FM tuner sections and dials, to take advantage of “simulcast” stereo with one channel on AM and one on FM. (Alas, the only station doing that near us was WQXR, in New York; since that was 80 miles away, we could only get the AM part.) To round out the system, we had two Dynaco Mk. III 60-watt amps.

Getting the amps was my job. Having very little money, I researched the hell out of my selection, to make sure I got maximum value. I’d hoped to find a book that would explain it all to me, but couldn’t, and resolved someday to write that book myself (which eventually led to my career in audio).

I took the next year off, living and working in New York. While there, I bought and built my first kit, an Eico HFT-90 FM tuner; its dial pointer glowed green in a pattern like an exclamation point that narrowed when you hit a station frequency. My dealer for that, Audio Workshop, not only sold kits but provided tools, bench space, supervision, and technical assistance, plus lockers where you could keep partly finished kits between sessions. Their technical assistance came in handy when I turned the Eico on and got smoke; I’d been supposed to wire pin 1 of one tube to pin 2 and pin 2 to pin 3; but then I went on to wire pin 3 to pin 4, too.

I noticed the Webcor had a two-position tracking force selector, a spring that could be moved from one hole to another. Having heard about the virtues of low tracking force, I moved it to its lower setting, then bought a stylus-force gauge to check the results. The gauge read up to 20 grams, but when I put the Webcor’s tone arm on it, it bottomed with a “clunk!” So, I replaced the Webcor: I got a Dynaco/B&O Stereodyne arm/cartridge that tracked at a then-remarkable 2 grams, and mounted it to a Weathers kit turntable.

Component turntables of the day had massive platters whose flywheel effect added speed stability. (The Fairchild, though, was available with an electronic speed control system.) Many, such as the popular Rek-O-Kut, had idler drives that interposed a rubber wheel between the motor shaft and the platter’s rim to gear the motor’s speed down. To provide the torque those heavy platters needed, the idler had to be heavy and stiff, and unless it was moved away from the motor shaft and platter when the turntable was off, the idler would develop flat spots, leading to thumps and speed irregularities in playback.

Dynaco/B&O pickup arm.

Dynaco/B&O pickup arm.The Weathers did it differently. Its speed was regulated by a motor much like an electric clock’s. Since such motors had little torque, the platter had to be a light aluminum stamping. And since the torque involved was so small, the idler wheel could be of rubber too soft to develop flat spots – so there was no need for mechanisms to move it out of the way when the turntable was off. Simple. And therefore very, very cheap – just $50, as I recall.

Switching from the Webcor’s ceramic cartridge to the Dyna/B&O magnetic one called for a preamp. I could have used my Heathkit, since my Dyna amps also had sockets that could power it, but I was so close to having stereo I switched to a Dynakit stereo preamp. Click here to view the Dynaco PAS-2 assembly and owners manual.

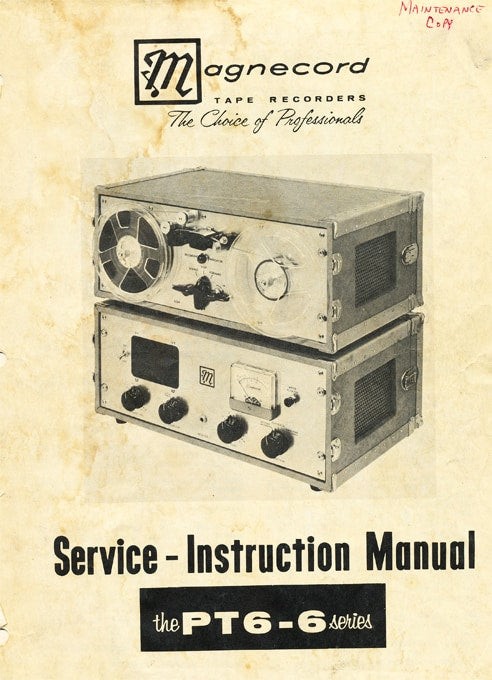

Then, since I already had those two Dyna amps, all I needed was a second speaker. Another Audio Workshop customer sold me a working RJ Wharfedale, which I temporarily paired with my RJ-housed Lafayette speaker until I could get a matching Wharfedale driver. Now my first real stereo system was a-a-l-most complete. A few months later, I swapped the Eico tuner for a Magnecord PT-6 mono tape recorder whose transport had been taken apart. With the aid of a Sams Photofact service manual, one of my former roommates put it back together for me.

Magnecord PT-6 service and instruction manual.

Magnecord PT-6 service and instruction manual.And that was that.

For a year or so, anyway…

Header image: Eico HFT-90 FM tuner, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Joe Haupt.

0 comments