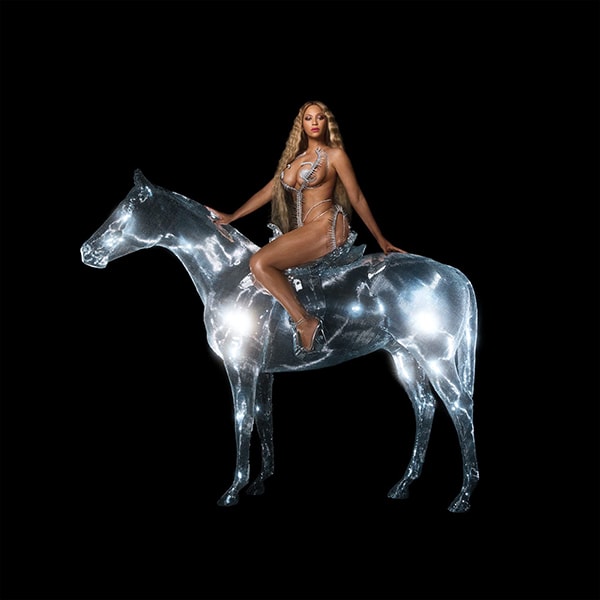

Renaissance (Columbia/Parkwood Entertainment)

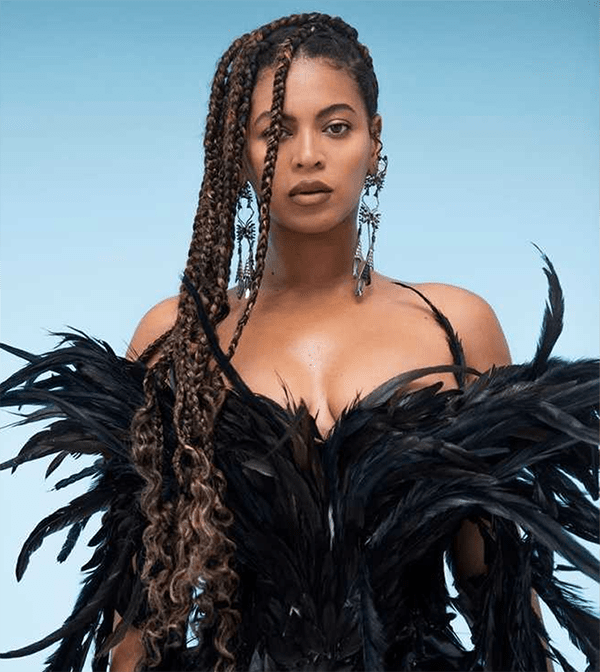

I’d always enjoyed Beyoncé’s music, from the time when she was in Destiny’s Child, the essential R&B girl group of the 1990s. That Beyoncé Knowles (now Beyoncé Knowles-Carter, married to Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter) would be a successful solo artist was never in doubt. If she now stands alone in popular culture as Beyoncé, whose eminence in today’s R&B/pop/soul is unquestioned, remember she’s been working at it for more than 30 years; her solo album debut was Dangerously in Love in 2003, almost 20 years ago. She works hard for the money, and the stature she enjoys.

When my department chair and I decided some years ago that a course I taught at St. John’s University, The Journalist as Critic, needed rebranding to increase signups, I half-seriously suggested calling it “The Institute of Beyoncé Studies.” I still use that phrase as a teaser in the syllabus for the class now known as Writing Music, Movies, and TV Reviews. In alternate semesters, I teach Writing About Music: Pop, Rap, Rock, and so the “institute” still has residual usefulness in describing the course in the school catalog.

How important Beyoncé is to my students was hammered home to me on December 13, 2013, when her fifth solo album, simply titled Beyoncé, had a surprise release at midnight. The final exam for the class was that morning, and one of the assignments was an album review. More than half the class wanted to write about that hours-old Beyoncé album.

Beyoncé’s work methods and visual presentation show an insistence on perfection. In pop music, this is not always ideal, even if the results are satisfying to both the artist and her ardent fans, which include a plurality of the world’s most influential pop music critics.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Mason Poole.

Her most recent album, Renaissance, was released July 29, 2022, and it is excellent in most ways, a seamless song cycle that maintains a crisp focus as an homage to club dance music cultures and subcultures since disco. It is a “perfect” party record: put it on and you don’t have to worry about changing the music until the final track is over. That track is “Summer Renaissance,” based on Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love,” the disco hit that is sort of ground zero for all of the rest of the rhythm music on this album. Beyoncé sings the breathless Summer swoons perfectly. It’s not a sample, it’s an “interpolation.” The US Copyright Office, in its online section on “Sampling, Interpolations, Beat Stores and More…” says:

An interpolation involves taking part of an existing musical work (as opposed to a sound recording) and incorporating it into a new work. While sometimes confused with sampling a sound recording, interpolating a musical work is different because it does not involve using any of the actual audio sounds contained in a preexisting recording. (Click on this link for more information.)

But it does require a license from the copyright owner of the previous work, which Beyoncé surely has done.

She hits all of her dance-culture marks so well: when a friend whose first language is Spanish came over when I was blasting Renaissance (it sounds good loud), I told her it was the new Beyoncé album. But she asked: When? And I repeated “new.” And she said again, “When? Eighties, Nineties?” She recognized these beats and rhythms as authentic creations or recreations of her youthful club-kid nights.

That means house music in its many specific forms: Chicago house, Detroit house, New Orleans bounce, and more underground sounds such as hyperpop, which my students say is a Tik Tok-sourced beat.

Since this is not my area of expertise, I thought I should listen with a scorecard helpfully prepared by Michaelangelo Matos, a trusted cultural historian and participant of this era. Matos prepared a guide for The New York Times (click on this link), a track-by-track guide to the specific sources, samples, and gestures on the album. For example, he helpfully describes the second and third tracks, “Cozy” and “Alien Superstar” as exemplars of Chicago house, of which, he writes:

“…often moves with a heavily pronounced swing, accentuated by octave-jumping staccato bass patterns. The canonical example is Adonis’s “No Way Back,” from 1986, and the bass line of “Cozy” plays like an inversion of it. The song is almost mnemonically recognizable as early Chicago house without simply sounding like homage.“

This was by far the most useful article in saturation coverage of Renaissance in the mass media and the Times in particular. Other articles, not so much. Wesley Morris, the Times’ critic-at-large, has won two Pulitzer Prizes, the highest honor in journalism, for criticism: in 2021, in his writings for the Times, according to the Pulitzer committee, “for unrelentingly relevant and deeply engaged criticism on the intersection of race and culture in America, written in a singular style, alternately playful and profound.” Morris also won the 2012 Pulitzer for his film criticism at The Boston Globe.

But something about Beyoncé turns this usually astute and clever culture critic into a squealing word-slinger without boundaries. About Renaissance, he wrote: “The range of her voice nears the galactic; the imagination powering it qualifies as cinema. She coos, she growls, she snarls, she doubles and triples herself. Butter, mustard, foie gras, the perfect ratio of icing to cupcake.”

It is true that she “doubles and triples herself”: What used to be known as “overdubs” is now stacking, and Renaissance is stacked so high so often that it is a minor miracle that it doesn’t topple over. The album is stacked so thick that it makes earlier efforts, from Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound onwards, seem like Joan Baez wandering with an acoustic guitar in a forest.

I bought the CD of Renaissance partly so I could get a much-better-than-streaming sound, but also so I could grasp the hundreds of words of credits, writers, producers, samples, and interpolations. These cover four full pages in the CD booklet, in unreadable white type at a font size I would describe as minus-two if that was mathematically possible: it is the tiniest font I’ve ever been confronted with for what I consider essential information.

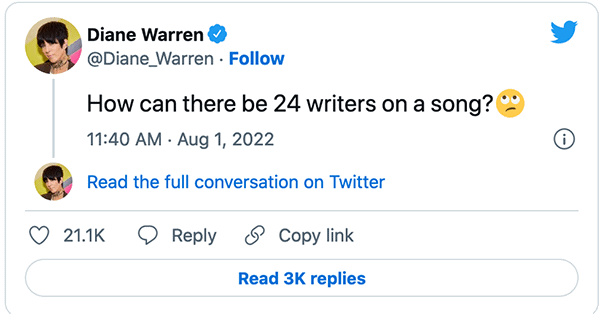

There is one song that credits 24 different songwriters. (“Alien Superstar,” which may be my favorite track on the record; it would segue nicely into David Bowie’s “Ziggy Stardust.”)

Songwriter Diane Warren faced fierce Twitter backlash for asking what to her was an obvious technical question. Warren might have thought she would be understood, since she wrote a song, “I Was Here” that was recorded by Beyoncé on her 2011 album, 4, and is apparently credited somewhere in the unreadable credits to Renaissance as well.

Producer writer/artist The-Dream [cq], aka Terius Nash, quickly become the de facto explainer: “You mean [how] does our (Black) culture have so many writers? Well it started because we couldn’t afford certain things starting out, so we started sampling and it became an Artform, a major part of the Black Culture (hip-hop) in America. Had that era not happen[ed] who knows. U good?”

Others noted the collaborative nature of hip-hop, which is certainly part of the Renaissance album. That’s part of Beyoncé’s gift: her vocal range and creative appetite ranges from Disney soundtracks (The Lion King: The Gift from 2019) was her previous album) to the down and flirty “I’m That Girl” that opens the album. She gives credit where credit is due, and to construct a Beyoncé album is to make use of an army of subcontractors, be they song samples, ambient sounds, a few rhythmic bars, instrumental passages, or interpolations, all meticulously stacked.

The August 1 tweet was followed by an August 2 apology by Warren. (Beyoncé herself said nothing.) As the dust-up recedes, though, the thousands of tweets by people who thought Warren needed a history-spank showed their own disregard for outstanding black songwriting achievements by, for example, Stevie Wonder, Curtis Mayfield, Roberta Flack, Smokey Robinson, Allan Toussaint, James Brown, Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, Thom Bell, Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, Holland-Dozier-Holland, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, Otis Blackwell, Billy Strayhorn, Miles Davis, Count Basie, Missy Elliot, Mary J. Blige, Alicia Keys . . . Do I have all day? I’ll fill the page. These people are now sampled; they were not samplers. They were and are songwriters.

The essence of any discussion of Beyoncé can’t avoid being about the costs and benefits of seeking perfection. I came to that discussion in a different class I teach, the Craft of Interviewing.

In 2014, the veteran actor Frank Langella was playing a limited run as the title character in Shakespeare’s King Lear at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. It was a triumphant opportunity for an aging, veteran actor: the role one trains for for a lifetime, since one can only be Lear with earned gravitas. Langella was 76 years old.

He was being interviewed in 2014 by Charlie Rose. About 32 minutes into the televised interview, Rose asks Langella about what he learned from playing Richard Nixon (in the movie Nixon/Frost): Langella volleys back, “When you’re caught, admit it.”

And then, this brilliant elder statesmen of American film and theater begins to talk about Beyoncé, and what he believes to be her lip-syncing, or using a backing vocal track, to sing the National Anthem at the 2013 second inauguration of President Barack Obama.

“I think Beyoncé is one of the greatest performers who has ever lived,” Langella said. “And I think she should have risked it, at the inauguration, because that is what great artists do. The fact is, I have such admiration for her, I’ve never met the lady, I doubt if I ever will, but I would say, when you’re my age, you’re going to be sitting with your grandkids on your lap, saying, I sang for the President. And they’re going to know you faked it. So what if you went flat? So what if you missed a note? Risk it! She’s a great artist! and she should have risked it. That is what aspiring to greatness is about, risk. The pursuit of excellence. Just jump. Some nights you’re terrible, some nights you’re transcendent, and some nights you’re steady. If you don’t risk, you’ll never be any of those things.”

Beyoncé acknowledged singing along to a backing vocal track. She told reporters that she’s a “perfectionist” and – due to a lack of rehearsal time – “did not feel comfortable taking a risk.”

“It was about the president and the inauguration, and I wanted to make him and my country proud, so I decided to sing along with my pre-recorded track, which is very common in the music industry,” Beyoncé told CBS News.

This is the Beyoncé conundrum. Revered not only by fans but by other professionals as one of the great talents of her lifetime, she refuses to risk failure or transcendence, because she’d rather look great, sound great, than strive to be greater.

I think one of her best performances is the live rendition of her song from Lemonade, “Daddy Lessons,” performed with fellow Texans, the band formerly known as the Dixie Chicks (now The Chicks) in difficult territory: the Country Music Awards TV show.

Renaissance is a great dance music album. But is it as great as Beyoncé could be without the meticulously constructed library of sounds? I don’t think that it is. I think the great Beyoncé album will be one that is recorded with a minimum of fuss, of overdubs, or stacking. It will be a record of great songs, originals, classics, songs of passion and heart that make demands on her talent. It would be much more tasty than feeding “butter, mustard, foie gras” to her courtiers.

Copper contributor Wayne Robins writes the email newsletter Critical Conditions at http://waynerobins49.substack.com

Header image: Beyoncé, Renaissance, album cover. Photo by Carlijn Jacobs.