Previous installments in this series appeared in Issues 146, 148, 149 and 151.

I feel like a rabbi talking a non-Jew out of converting to Judaism. It’s incumbent on him or her to try to discourage any would-be Member of the Tribe, in preparation for the hardships and challenges that lay ahead. That’s how I approach those who would embrace open-reel tape, if they don’t already own legacy machines and tapes, because rediscovering open-reel tape has none of the benefits of the return to vinyl (or even cassettes): there’s never been a time when you couldn’t buy a turntable or new vinyl, and the format has been revived beyond even Mikey Fremer’s wildest dreams.

Everything about open-reel seems to be a cautionary tale. As has been discussed before, aside from Ballfinger and a few restorers of vintage decks, there are precious few new machines to consider, let alone afford. You have to buy second-hand, and hope you bought a deck that needs little work, or at least is the sort for which spares exist. Copper has gone into depth on the topic of the hardware; this article is about the caveats of which you should be aware when buying used pre-recorded tapes.

Brand-new pre-recorded tapes, from companies I call The Open Reel Revivalists, aren’t enough of an inducement to get into open-reel unless you are loaded, and have catholic tastes when it comes to music. Admirable as they are, the brand-new 1/2-track, 15 ips tapes cost a bundle and don’t necessarily address most people’s musical preferences. I suppose the trap for those who only want brand-new machines and tapes is not unlike having a Bugatti Chiron while living in Monaco: nowhere to go, and nothing to do other than admire your purchase while hardly enjoying it.

As I have stated before, my obsession has resulted in the acquisition of eight machines and 2,300 pre-recorded tapes from the time frame I categorize as The Original Open Reel Era, which ended in the mid-1980s. This immediately sets a cutoff point regarding repertoire. Anyone who wants any material recorded after, say, 1985, regardless of the artists, is sh*t-out-of-luck. So, Caveat No. 1 is: Don’t Buy Into Open-Reel Tape If You Hate Easy-Listening, Middle-of-the-Road Pop, Classical or Soundtracks and Show Scores.

As drastic as that sounds, that’s pretty much what’s available out there. I’m saving my observations about the dearth of rock music and other genres for a future column, but suffice it to say that the available repertoire is limited to whatever genres appealed to the stereotypical (pun intended) audiophile of the era. This, of course, is no issue for those who do prefer classical, soundtracks, etc., but for Baby Boomers partial to rock, soul, country, funk and other post-1960s genres, the pickings are slim. Again, I will discuss the low survival rate of rock tapes in an upcoming column.

Caveat No. 2 is about condition. Sorry to repeat myself, but 2,200 of my 2,300 purchases came from eBay and without exception, all were offered as seen, with the vendors noting that the tapes are untested, as they had no access to tape decks. What this tells you is that the tapes sold on eBay are probably collections found in an attic, garage or basement after a parent or grandparent has passed on, or other situations in which the vendor has found a pile of tapes with no interest in them for his or her own use.

Again, a future column with discuss how I have dealt with this, and how I have thrown out around one in every 30 tapes – but that ain’t bad when you consider what’s worth keeping from every pile of 30 or so used LPs you might acquire. Indeed, one of the upsides to this adventure is the unbelievably high survival rate of Original Open Reel Era pre-recorded tapes (rock notwithstanding). I can only attribute this to the likelihood that most were owned by audio enthusiasts who knew how to handle and store them. Oh, and who respected them because they have always cost twice that of contemporary LPs.

As for Caveat No. 3, it’s about prices. If this was 2018 or even 2019, I wouldn’t be telling you about what inflation has done to the prices of used tapes. If I keep referring to eBay, that’s because it is the most omnipresent source, and is a yardstick for values in most categories, e.g. what the going price is for a pair of vintage Stax headphones or Montblanc fountain pens. What’s happened is that interest in open-reel tape is enjoying a near-vertical trajectory, even if it is only within a tiny community (or minuscule cult). The number of devotees may be negligible when compared to vinyl returnees or newcomers, but they tend to be fervent, seasoned audiophiles.

A result of the renewed interest in open-reel tape is 100-to-200 percent inflation in the price of old tapes. Even dreck that couldn’t command $5 two years ago (which is the value of a decent empty plastic spool) is now $10-$25 plus postage. I won’t identify this “dreck,” only to say that there are dentists’ offices that wouldn’t touch this stuff as background music. If you do decide to test the eBay waters, expect to pay $20-$30 for tapes described as in good condition, irrespective of any genre except rock. Add another zero to that for the top rock artists.

Caveat No. 4 will only affect you if you go global, but it addresses something that infuriates me, and wish I desperately want to save you from suffering: the utter swill issued in the UK. From what I can tell, the USA, the UK and Japan were the only territories which manufactured pre-recorded open-reel tapes in any numbers, with the USA by far the most prolific. My guess is in excess of 10,000 titles were produced in the USA over the roughly 30-year lifespan of the pre-recorded reel-to-reel format. What I can tell you is that out of my 2.300 tapes, only six are not from the USA.

Those six include two Japanese tapes – a Percy Faith album and the soundtrack to South Pacific – but I am at a loss to tell you how many titles were issued in Japan, and the one source I should have asked was the dear, departed Tim de Paravicini. Suffice it to say, he had dozens of Japanese open-reel tapes, for which he paid gigantic sums, and he confirmed, before I even acquired my two, that they are without peer. I heard his Miles Davis and Ramsey Lewis tapes, and demo tapes from TEAC, and sat there slack-jawed. Yes, they’re that memorable.

The late Tim de Paravicini and some of his Japanese pre-recorded tapes.

Before getting to the actual target of Caveat No. 4, I should pass on what Tim did tell me. He was certain that the Japanese tapes sounded so good because the tape stock was absolutely first-rate, while duplicating was undertaken in real time. As for the US-sourced tapes, he said the reason they sound as good as they do, despite certain economies and some labels taking liberties with track playing order, was that the duplicators such as Ampex were scrupulous in maintaining their recording “slaves,” even if the copying was at high speeds. Most of the tapes I have are on decent stock, Ampex or Scotch, and I have not come across one tape which needed baking.

(Brief aside: Another authority confirmed to me that the tapes which do suffer from gumming up or shedding, thus needing baking, were specific stocks of studio-bound professional blank tape, not the stocks used for commercial pre-recorded tapes.)

Note that the Japanese tapes I have seen are 7-1/2-inch ips 1/4-track tapes, while Tim had some real gems on 10-inch spools that played at 15 ips 1/2-track. US tapes began as 1/2-track 7-1/2 ips, then 1/4-track was introduced, and ultimately the speed was cut to 3-3/4 ips for cost savings. It also seems that the loftier the artist, e.g. Leonard Bernstein, the more likely the tape was of the higher speed. Rock was treated like a leprous scab, so most are 3-3/4 ips.

Oliva de Paravicini and a box of Japanese pre-recorded tapes.

More of Tim de Paravicini’s Japanese open-reel tapes.

Now the caveat. The third market, the UK, issued a smattering of 7-1/2 ips tapes, both 1/2 and 1/4-track. The four I own are classical and only so-so sonically, and I have no reason to believe that there were too many other titles. Instead, we get to the target of my loathing: the “twin-track mono” 3-3/4 ips atrocities issued by EMI and an affiliate budget label.

A history lesson is in order here. In the 1950s and 1960s, the British were relatively impoverished compared to Americans. Audio separates were the province of well-paid professionals. If you study Hi-Fi Yearbooks, however, you will see a plethora of cheap open-reel tape recorders, dozens of them. Why? Because the cost of LPs was so high that British music lovers of average means taped off-air, e.g. BBC concerts, or copied friends’ LPs. As a blank tape that would hold two LPs cost half the price of one album, you can see the instant savings.

Despite this, EMI issued a slew of tapes, from Frank Ifield to Nat King Cole, Shirley Bassey to the Yardbirds, Cliff Richard to Johnny Mathis, Manfred Mann to P.J. Proby. These came on 4-inch spools in 5-inch boxes, the irony being that the packaging was better than most of the US offerings while – unlike the USA – every tape had dedicated, printed leader-and-tail, showing some respect for the end-user. But that is not unlike putting lipstick on a pig because the sound was truly, inescapably execrable.

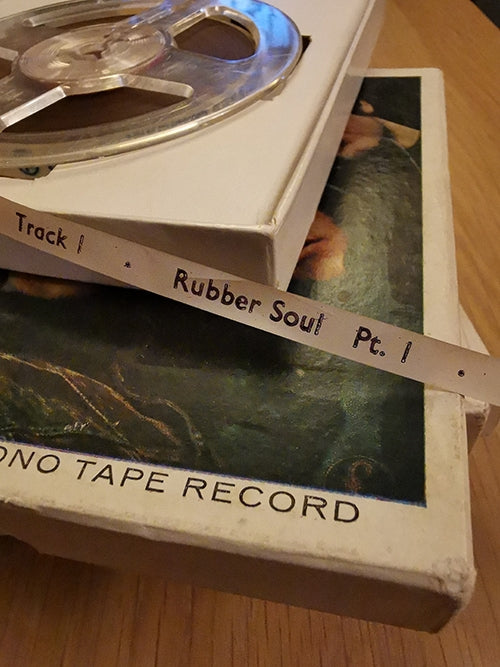

An EMI open-reel tape of the Beatles’ Rubber Soul showing the pre-printed leader.

Why do I mention them at all? Unfortunately, for me living in the UK and logging on eBay.co.uk, the algorithm daily bombards me with these, which fill screen after screen after screen. And they don’t shift. People aren’t stupid. But there’s a wrinkle to this: the Beatles tapes fetch as much as the decent ones from the USA on Capitol and in stereo. Why? Because they are sold as artifacts and memorabilia to hard-core Beatles fans. They have no worth at all beyond mere objects.

Then comes another twist: it has been pointed out that these are the only means of getting the Beatles’ mono mixes is on open-reel tape. Despite the sound being muddy and unpleasant, there’s a cadre of enthusiasts prepared to shell out big money for these. Wrap your head around that one, and then believe me when I tell you that open-reel tape enthusiasts are as zealous as vegans.

Good packaging, bad sound: EMI open-reel tapes.

0 comments