“(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life” was the Billboard Number 1 Hot 100 hit single from the 1987 Dirty Dancing soundtrack album, one of the biggest selling (over 32 million copies) in history. Performed as a duet by Bill Medley of the Righteous Brothers and Jennifer Warnes, the song went on to earn both an Academy Award and a Golden Globe award win for its writers, John DeNicola, Franke Previte, and Don Markowitz, and remains a perennial radio favorite.

DeNicola and Previte also composed the soundtrack’s other big hit, “Hungry Eyes,” which was performed by Eric Carmen. Ironically, the demo of the song, featuring DeNicola with Previte and singer Rachele Cappelli performing the duet parts, was used for the actual dance sequence when Patrick Swayze and Jennifer Grey filmed their scenes, as the Medley and Warnes version had not yet been completed. In subsequent interviews, Swayze would frequently mention that he preferred the demo version to the hit single release – perhaps a foreshadowing of DeNicola’s future production expertise.

As a professional musician, John DeNicola made his first industry mark as the bassist for jazz fusion group Flight, which was signed to Motown Records. After stints as bassist for Paul Young and Corey Hart, DeNicola focused on songwriting and production, and subsequently worked with a range of artists, including Eddie Money, John Waite, and Bernie Worrell of Parliament/Funkadelic, as well as British prog-rock Renaissance siren Annie Haslam, and a band named Kara’s Flowers, which would later rename itself as Maroon 5.

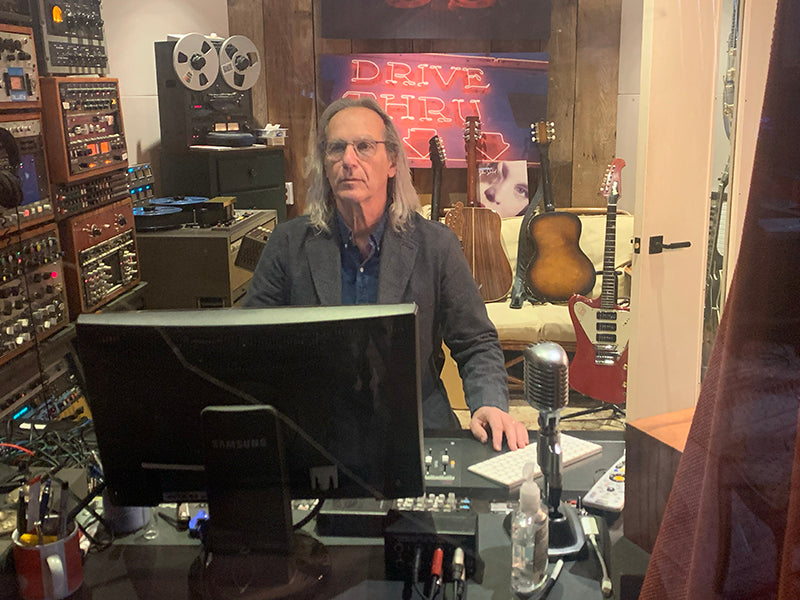

Although his involvement with Dirty Dancing may have been the commercial pinnacle of his career to date as a songwriter, John DeNicola has continued to be active in the music industry as a songwriter, producer, multi-instrumentalist, recording artist, record label owner – and most recently, as an audiophile-market product supplier of commercially distributed recordings on 1/4-inch analog reel-to-reel tape. Copper had the opportunity to ask John DeNicola about his recent foray into analog reel-to-reel releases, and his body of other work.

John Seetoo: After all the work you've done in various audio formats, what motivated you to now release recordings on 1/4-inch 15 ips analog tape? Was it a preference for the sound, or was it something else? At a retail price of $350, how has the market reaction been?

John DeNicola: While looking at a DIY single-ended tube amplifier company website that also specialized in the sale of reel-to-reel tape machines, I noticed that they additionally offered 1/4-inch tape recordings of a few classic records – that were all sold out. After further research, I saw a few other websites offering 1/4-inch tape recordings. I noticed that there was a limited choice of music, so I thought I'd add a few more choices for them. The sound is way better than any of the other formats, to my ear. Even better than vinyl. It's the closest thing to being in the recording studio and listening.

I just followed my interest, which is the way I usually work, and only now am I really getting the word out. I should mention that it takes two reels to fit a record and each blank tape is very costly, resulting in that higher price category.

JS: Are you handling the transfers at your own studio, or are you outsourcing them to a different facility?

JD: We do them here at my studio in upstate NY on my Studer B67 1/4-inch reel to reel recorder. [It’s]

JS: Analog cassettes are becoming a retro trend. Is this a market that you also are considering, and what technical changes would you make to maintain your sound quality standards as closely as possible, given both the tape dimensions and operating speed differences?

JS: Have you used your studio for any of your other collaborations released on your label, Omad, or on other labels?

JD: Yes, for the most part I record all my Omad projects here in the barn with some overdubs in my NYC studio. Rust Dust, Peter Lewis, the Sighs, Fovea, and Robert LaRoche were all done here in the barn.

JS: Our editor grew up in the town of Smithtown like you did and went to Hauppauge High School. Copper's Jay Jay French played clubs in the Tri-State area as a member of Twisted Sister. Are there any memorable musical experiences you can share from growing up and playing in bands on Long Island? Or did you move to New York City at an earlier age?

JD: Oh, for sure. For many years, I was in a cover/original band named Sweetback. It was a seven-piece band with horns and an amazing singer, Tim Lawless. Actually, Rich Cannata went from our band to play with Billy Joel for many years. We played all over Long Island, and in particular, we played Monday nights at Tuey's in Setauket for many years. Then later on, I played bass in a jazz fusion band named Flight, which recorded for Motown Records. We rehearsed in Wantagh six days a week for six hours a day. Erykah Badu sampled our song, “Face To Face” for her hit, "Back In The Day." (We also) played at My Father’s Place in Roslyn a number of times with both Flight and Corey Hart.

JS: When did you decide to make the transition from musician to songwriter and producer?

JD: My songwriting started when an original band I was playing in needed songs. Before playing in original bands, I was playing bass in Corey Hart's band. I think Rich Cannata was producing him and he asked me to play bass with him. I had conversations with Corey and he stressed the importance of writing music. When I had success writing the songs from Dirty Dancing, I was thrust into the "songwriter" category, and as songwriting turned more into producing tracks for artists to sing on, my production chops were honed. A&R people were less and less about hearing the bones of a song and more about a finished production, so they could hear the song as it might end up sounding finished. Then, after years of writing and producing tracks, I would sometimes take a break from writing and focus on producing as a way to kind of distract from the writing process and put my producing/engineering hat on and work with bands that I found or that found me.

JS: Your musical collaborations with Franke Previte, Maroon 5, Eric Carmen, John Waite, Eddie Money, Sugar Jones and the Sighs in pop/rock, Bernie Worrell and Kristine W. in R&B/dance music, and Jeannie Kendall and Steve Holy in country music all make logical sense, given your roots as an American Oscar-winning pop songwriter, Motown artist and former jazz/fusion bassist. Annie Haslam of the British prog-rock group Renaissance seems to be an outlier. How did that collaboration come about, and what did you accomplish together?

JD: I was introduced to Annie Haslam when her A&R person heard a song I had written with Kit Hain entitled "Further From Fantasy." Larry Fast was producing. Larry asked me to work with him on the tracks for the song, as I had a bunch of synth tracks with sounds they liked. But to me, Annie Haslam is an artist I can relate to musically. She has such a perfect and beautiful voice. As it happens, it seems either A&R people were looking for more songs for women or I gravitated to songs for women – not sure which it is, actually.

JS: Moby Grape was one of the early San Francisco groups of the 1960s. How did the Moby Grape/founding member Peter Lewis relationship start, and have you done any kind of work together that has been unreleased?

JD: I was a big Moby Grape fan growing up and loved their records. I was particularly influenced by Bob Mosley as a bass player and was always moved by his amazing singing voice.

In the early days of the internet, I typed in “Moby Grape” and was connected to an early website that had been set up. I got connected with their publishing administrator and he put me in touch with Peter and the band. They were just getting the rights to their name back from an early manager and once again able to perform as Moby Grape, and came here to New York City and played at Wetlands before it closed. I actually met with them and sat in on a few songs at a few of their East Coast gigs.

I kept in touch with Peter and at some point, he sent me some demos that he did with his daughter, Arwen Lewis, which contained a few Moby Grape songs. I suggested we do an album of Moby Grape songs from a female perspective and they came here to New York and we completed a record of 12 Moby Grape songs featuring Arwen. I also produced the Peter Lewis Record, The Road To Zion, that Omad put out in 2017. We just so happen to be finishing up a new record with Peter, for which I have co-written six songs, and the rest are Peter originals. I am in mixing mode as we speak and it should be out in the spring.

JS: The Why Because features your versions of songs that you wrote but were previously recorded by other artists, most notably your most familiar hits: "(I've Had) the Time of My Life" and "Hungry Eyes," which were the cornerstones of the Dirty Dancing soundtrack. Were the versions you released the arrangements that you envisioned for the songs originally when you first composed them, or were they the result of self-reflection over the years as to how the songs speak to you in the present day?

JD: When I decided to record my own songs, I thought about “Hungry Eyes'' and asked my son for ideas on how I should approach it. He said that a lot of modern indie rock bands put elements of ’80s synth-pop into their modern recordings. We took elements of the original but added a modern indie rock feel. I thought that it would be a great way to approach it. Jake played drums in that style and away we went.

So “Hungry Eyes'' wasn't too hard to approach, but “Time Of My Life” was a lot harder to come up with a fresh way that would be different enough from the original. The original is so well-known and done so well with some of the greatest singers in the world singing on it. Bill Medley and Jennifer Warnes are so perfect in that original version. So, I was at a loss and was not going to put it on the record. Then at the last minute, I decided to just strip it down with an acoustic guitar and some French horns. I just do a verse and a chorus and bridge out. It's really an homage to the song and what it has meant to me. It closes the album, The Why Because.

My follow-up record released in 2021, She Said, is made up of songs I wrote for myself as an artist. It was interesting to me to see who I am as an artist after all these years of playing in bands backing someone up or writing for someone else. It was really cathartic for me to be able to do a record free from any constraints on what I could do and without having to get a consensus from others.

JS: What do you use for your home hi-fi system? What music recordings would you use as a reference to audition stereo equipment for your listening pleasure and why?

JD: I have multiple systems in various places. I have a single ended Decware tube system with very efficient speakers that have both front-facing speakers, and Decware Radial HR-1 speakers with a VPI turntable. I also have a ’60s McIntosh system with an MX110 receiver and MC240 amplifier, Legacy speakers, and also another VPI turntable with a Dynavector 10X5 cartridge. And then, scattered in different places, I have three Fisher 500C receivers with various types of speakers. In the studio, I have a McIntosh solid-state power amp, ATC and Audix speakers, and two reel-to-reel machines: the aforementioned Studer B67 and an Otari MX-5050.

As far as auditioning records, there are so many. Acoustic Sounds out of Salina, Kansas (see Copper Issue 33 for an interview with Acoustic Sounds founder Chad Kassem) make great direct-from-tape master LPs or UHQR