We began our interview with mobile recording pioneer David W. Hewitt in Issue 178. Hewitt and his mobile trucks recorded thousands of concerts from hundreds of artists across the United States and abroad, including Neil Young, Barbra Streisand, Simon and Garfunkel, David Bowie and countless others. We conclude the interview here.

John Seetoo: As you are primarily tasked with capturing the moment on your projects, were there any shows or artists who you recorded that you would have liked to have had the opportunity to also mix those record(s)?

David W. Hewitt: No, is the short answer. I think of the live mix as having one “life.” Remixing the multitrack recording is a different art. It can have endless versions into the future. I prefer to move on to the next performance. Done and dusted as my British friends say…

JS: What are some “impossible” situations where something went terribly wrong and you had to create a never-before-used workaround to salvage the recording(s)?

Side Trip: The Black Truck Crash (excerpted from On the Road):

The year 1989 was very difficult for me and my small band of road rangers. In the early morning hours of February 6, the Black Truck struck black ice on a high crowned country road and rolled over. Thanks to the skill of driver Phil Gitomer, we avoided crashing into a spinning car in front of us, or the surrounding trees.

My seat belt failed and I was thrown into the bunk instead of the windshield, saving me from more serious injury, but knocking me unconscious. Phil survived with lots of bruises and valiantly directed salvage operations to get the Black Truck home.

As the medics hoisted me up out of the sideways cab, I tried desperately to remember WTF happened and where we were supposed to be going!

By the time I arrived at the ER strapped on the board, I started to remember – DAMN! We were heading for New York to record Harry Connick Jr. at the famed Algonquin Hotel!

I grabbed a passing intern and got him to call my wife Dusty – and do not tell her what happened! She must call our friend Kooster McAllister and get him and the Record Plant White Truck over to record the gig! She did and he did and saved the day for Columbia Records and Harry Connick Jr. That show would help launch Harry’s career and we would record him many times as he became a star. My son Ryan engineered Harry’s [2019] album, True Love: A Celebration Of Cole Porter. It’s a glorious return to his Big Band roots.

R.I.P. Black Truck, my faithful road companion.

JS: You mention in your book that while working with Prince, he would sometimes record using your mobile truck, parked near his home. The Rolling Stones’ Exile On Main Street was also a “studio” album recorded by a remote truck. Were these rare exceptions, or did you also use your trucks for other notable “non-concert” recordings? Was setting up for overdubbing tracks something that required any unusual workarounds, as opposed to doing live multitrack recordings?

DWH: Here’s another story from my book:

Prince’s Christmas Eve

Prince started rehearsals for [his] 1985 tour just before Christmas at the Saint Paul Arena. He hired a real performance venue so that Showco could set up their complete touring sound system and tune it for the Purple Rain tour.

On Christmas Eve, Prince called a wrap, but his road manager came out to the remote truck and announced, “PRN (Prince Rogers Nelson) wants the truck out to his house.” I felt bad for my crew, but we were on the client’s clock. So we saddled up and brought it out to Prince’s original, rather modest ranch house.

We were let into the house and even though there had been a studio there, the console had been removed and obviously we would work in the remote truck. I became the default electrician, looking downstairs for the main electrical panel to power up the truck. Let’s see, probably not the red room with the heart-shaped bed and all the mirrors. The laundry room had an Ampex MM-1100 16-track recorder sitting there, covered in clothes. (I preferred the later MM-1200s myself.) There was a 200-amp service to hook up the remote truck.

Prince’s assistant engineer, Susan Rogers, knew what was expected and already had the 24-track tapes of a Sheila E album that Prince was producing. She had that cued up as Prince made his grand entrance, nodded to the crew, and immediately plugged in his bass to overdub it on a few tracks. He seemed quite amused, played around with a guitar, and joked with Susan while he did most of the engineering.

In what seemed like the shortest session I’d ever attended, Prince happily thanked us all and went in the house. We just looked at each other and pronounced it a Merry Christmas. That’s a wrap!

I think maybe the man just wanted some company on Christmas Eve.

JS: You were a friend and colleague of my engineering mentor, the late Dennis Ferrante, when you both worked at the Record Plant. You mentioned that you seldom worked together, as you were usually recording from the remote trucks, while he was primarily studio-bound. However, you both worked together in 1978 on the Texxas Jam music festival. What can you tell me about that experience with Dennis working alongside you that wasn’t included in your book, in which you state it seemed like it was 120 degrees!

DWH: That Texxas Jam gig was fraught with problems. We had just finished recording a band on top of the World Trade Center helicopter landing pad days earlier. I was also trying to finish building the new Record Plant Black remote truck. We did have its new custom API console [already] built, so we installed that in the old White Truck and sent it off. It was now so overloaded that it blew several tires on the way to Dallas. Once we got there, it was a scramble to patch all the new wiring in and hope it worked. Dennis was a big help, keeping producer Jack Douglas and the band Aerosmith assured we had it under control. The sun was blazing and the feeble truck air conditioner failed! It was 120 degrees on the stage. We scrambled [to find] a window air conditioner [for the truck] and cobbled up a hose into the side cable hatch. Interior light out, shirts off, we managed to get Aerosmith and a few other bands recorded. Thankfully the band went on at night and rewarded the roasted crowd with a fantastic show. (Chapter six in my book has a lot more Aerosmith stories for you.)

David W. Hewitt (L) with the late Dennis Ferrante. Courtesy of David W. Hewitt.

David W. Hewitt (L) with the late Dennis Ferrante. Courtesy of David W. Hewitt.JS: You mentioned the story of the Black Truck crash. Aside from weather-related road hazards, what other kinds of dangers have you encountered?

DWH: I have traveled my whole life, first as an Air Force brat and a veteran, then in sports car racing and 44 years of live recording. I’ve learned to look out. The danger is almost always our fellow humans.

I did not go to the original [1969] Woodstock. I had a race planned. My brother Lynn went and I heard about it for years…

Then came Woodstock ’94 or as it became known, “Mudstock.” We did take the Silver remote truck and joined many others. It’s in the book. The worst danger I experienced in our business was the Woodstock ’99, or “Riotstock” as we called it!

When they [had] announced yet another Stock, Woodstock ’99, I saw that it would be at Griffiss Air Force Base, a deactivated SAC (Strategic Air Command) base. I was familiar with it as an active B-52 bomber base with nukes on the ready. Well, that has to be well organized; what could go wrong? I would soon find out. There were way too many producers involved. There was strict security at the gates [who allowed] no bottles, even water, [to be brought in], which would turn out to be disastrous. The concession stands were hugely overpriced for the dry fans roasting in the sun! By showtime there were some ugly confrontations. Then the riots, the fights, the fires and looting…we were lucky to get out in one piece. I suggest you watch the documentary on Netflix: Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99.

JS: In doing some live recordings you’ve worked with a number of highly-regarded producer/engineers like Bob Clearmountain and Ed Cherney. Were there any tricks or tips that you saw them apply from their studio experience during live recording that were new to you? Conversely, did you have any live recording techniques that surprised them and that they would later utilize on their studio recordings?

DWH: Working with Bob Clearmountain, Ed Cherney and Elliot Scheiner, I found they shared three tricks in common. They were calm, confident and masters of their craft. Most importantly of all, the musicians knew they could be trusted. They were always inspirations to me.

After many years of working with Elliot Scheiner, he confided that after our first remote gig together, he would always book me for his live work! That first gig was a monster. It was at the United Nations General Assembly in New York. An international UNICEF fund raiser for world hunger, a huge world TV broadcast with many stars of the day like the Bee Gees, Rod Stewart, and Donna Summer. An orchestra and bands as well…two audio trucks and lots of television trucks.

Not your average rock band gig. It was Elliot’s first big live TV show. He did a great live mix and over the years we would do many monsters together, like Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Festival, and events for Eagles and Sting.

Those tricks we found in common were: advance preparation, calmness (unless someone really deserved some “correction”), and – enjoy the music!

JS: Looking at live music performance from the 1970s to the present, many technological developments in PA systems, microphones, monitoring, time-aligned speakers, computerized consoles, digital outboard gear and so on have changed concert sound for audiences in a variety of ways. How have you seen these changes impact your work, and how important has your rapport with the front of house engineer had a bearing on your final results?

DWH: The technical developments since the 1970s would fill an encyclopedia; they change almost by the minute! Maybe my next book [will cover them].

The importance of rapport with the FOH engineer remains very important. That person, often more than one person these days, I think of as the pilot of the airplane. They prepare it, set it up and fly it, and hopefully land it safely.

They are usually appointed by the stars and the management, so you need to connect with them, hopefully in advance of the show you are recording. Advance work is very important. Walking in on show day, you had better know who is mixing FOH!

Over the years I have made some great friends of FOH mixers. The late Jack Maxson, longtime Showco FOH Mixer for the Rolling Stones; Tim Mulligan, Neil Young’s FOH mixer for many years; and Clair Brothers FOH vets Dave Kob and the infamous (I’m joking Trip Khalaf! Great mixers all.

JS: Your son Ryan has become an audio engineer of note in his own career, which started with his learning from you. He is presently mixing a new project with Neil Young, your longtime friend and client. Are you at liberty to mention anything more about that project and Ryan’s role? Did Ryan’s familiarity with analog recording, which is Young’s preferred medium, have a bearing on his involvement?

DWH: The new Neil Young album, World Record, has been released. Ryan described his recording process with Neil Young and Crazy Horse as all-analog, using producer Rick Rubin’s Shangri-La studio’s API console and Studer tape recorders. His vast collection of mics was augmented with Ryan’s mics, some of which go back to my 1960s Regent Sound days.

When Rick brought Ryan in to engineer, Neil didn’t know he was my son, so that brought a big round of laughs and stories about Rust Never Sleeps! Yes, Ryan’s expertise allowed [them to record in] analog down to the last mastering step. All Studer tape machines, like [those] he grew up with in our remote trucks. But he is way beyond me with his editing skills and mixing abilities! I’m still waiting for my copy of the record…

Ryan Hewitt, Neil Young and Rick Rubin at Shangri-La studio. Courtesy of Ryan Hewitt.

Ryan Hewitt, Neil Young and Rick Rubin at Shangri-La studio. Courtesy of Ryan Hewitt.JS: In 2022, what advice would you give to an engineer just starting out who wants to specialize in live concert recording?

DWH: Well, I would recommend listening to one of my favorite bands: The Byrds singing “So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star” (just substitute a remote truck for the guitar in the lyrics).

“So you want to be a rock and roll star?

Then listen now to what I say

Just get an electric guitar

Then take some time and learn how to play…

The price you paid for your riches and fame

Was it all a strange game? You’re a little insane…”

I also recommend a Peterbilt truck!

JS: If you were to outfit a new remote recording truck now in 2022, what would your equipment setup include from your old Black or White trucks, and what modern gear would replace the old equipment?

DWH: Frankly, I would not be interested in building a new remote truck today. The costs to do a proper design are only for wealthy hobbyists. When I read Copper I see so many talented young musicians finding ways to record their music and doing great work, much of it live. I’m happy to support them and listen…off the road!

JS: Your career discography credits also include work on a number of studio recordings. Do you have any favorite studio sessions or records in which you’re most proud of your contributions?

DWH: Depending on where you look for discographies on the internet, you may find several other David Hewitts who did studio recording. It’s why I finally started using my middle initial W, David W Hewitt, on all my work. You can try searching “David Hewitt Engineer” or go to my site davidhewittontheroad.com for more accurate information.

I have actually recorded very few studio albums, but one I am very proud of is Life in This World by David Calhoun on Motéma Music, catalog number MTM-119. My friend Sam Berkow brought me into iiWii studio, one that he had proudly designed. Sam had also designed the acoustics of the last remote truck I built. John Hanti is the owner of SST Studios and rentals and has built an incredible recording complex, with a large collection of vintage microphones and recording gear surrounding an original Focusrite console, one of only six made.

JS: Do you listen to your past recordings at all? If so, what are your favorites? What is your personal listening setup like? Copper audiophile readers are always curious as to what the engineers and producers own for their own personal music listening outside of the job.

DWH: Past recordings were like a moving target. If it was a major artist or show the live recording might come out quickly. [For others] it could take months, years, or never! During my career as a live recording engineer and remote truck owner, I couldn’t do much studio work without missing live gigs. Good way to lose clients.

Funny, I still find old live records out there, some I didn’t know were ever released. Recently found a very rare David Bowie Live Nassau Coliseum ’76 on vinyl [that] we recorded on April 23 ,1976.

Over the years, I’ve had many different personal audio systems. I still have my original Bryston 11B preamp and 4B amp powering my classic B&W 801s and B&W Matrix speakers. All have been well maintained. Rega turntable, Ortofon cartridge. Apogee Duet for digital sources. Trusty old Sennheiser HD580 headphones. California Audio Labs Delta CD transport, and finally my ancient Nakamichi CR-7A cassette player with adjustable azimuth.

To be honest, I often just listen to classical and jazz radio stations on my Sonos [wireless] speakers.

For more stories, read David W. Hewitt’s book, On The Road: Recording The Stars in a Golden Era of Live Music, available at https://davidhewittontheroad.com and from online retailers.

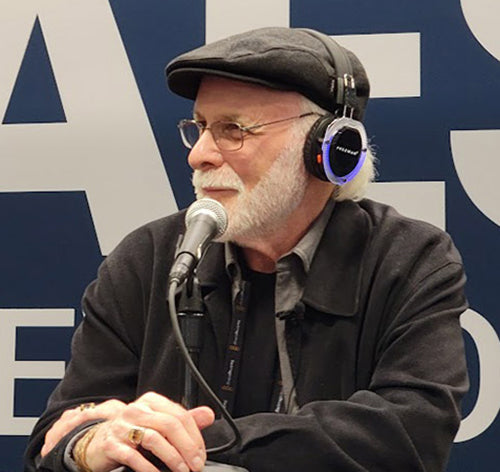

Header image courtesy of John Seetoo.