When Marc Bolan and David Bowie put Glam Rock on the map, they both owed a large part of their sonic success to a New York-born musician and producer named Anthony Visconti. With a combination of musical theory, audio engineering knowledge, personal musicianship, and a no-nonsense rock and roll attitude, Tony Visconti was responsible for such classic hits as “Bang a Gong (Get it On)”, “Young Americans”, “Jeepster”, “The Slider”, “Ashes to Ashes”, and “Heroes”, among many others. He also went on to work with a wide range of artists across the musical spectrum and has continued performing live on bass with Holy Holy (featuring Woody Woodmansey from the original Ziggy-era Spiders From Mars band). Tony Visconti was gracious enough to take some time to speak with John Seetoo for Copper about his philosophies on music production and about his newly released solo album, It’s a Selfie.

John Seetoo: You’re best known for your longtime association with David Bowie, perhaps to the detriment in your discography of an incredibly diverse range of other artists whom you’ve produced: Paul McCartney, The Moody Blues, John Hiatt, individual members of Yes, Ralph McTell, Thin Lizzy, Alejandro Escovedo, Kristeen Young, Annie Haslam, The Seahorses, The Damned, Iggy Pop, and of course, T. Rex, to name a few. This covers glam, punk, folk, prog, roots, and pretty much every musical genre—including jazz, with your recent work with Esperanza Spalding.

Do you have a single overriding concept as to how you like to produce music in general, or do you put yourself in a different mindset for each artist’s project, bearing in mind certain sounds, microphone techniques, etc., particular to the music genre at hand?

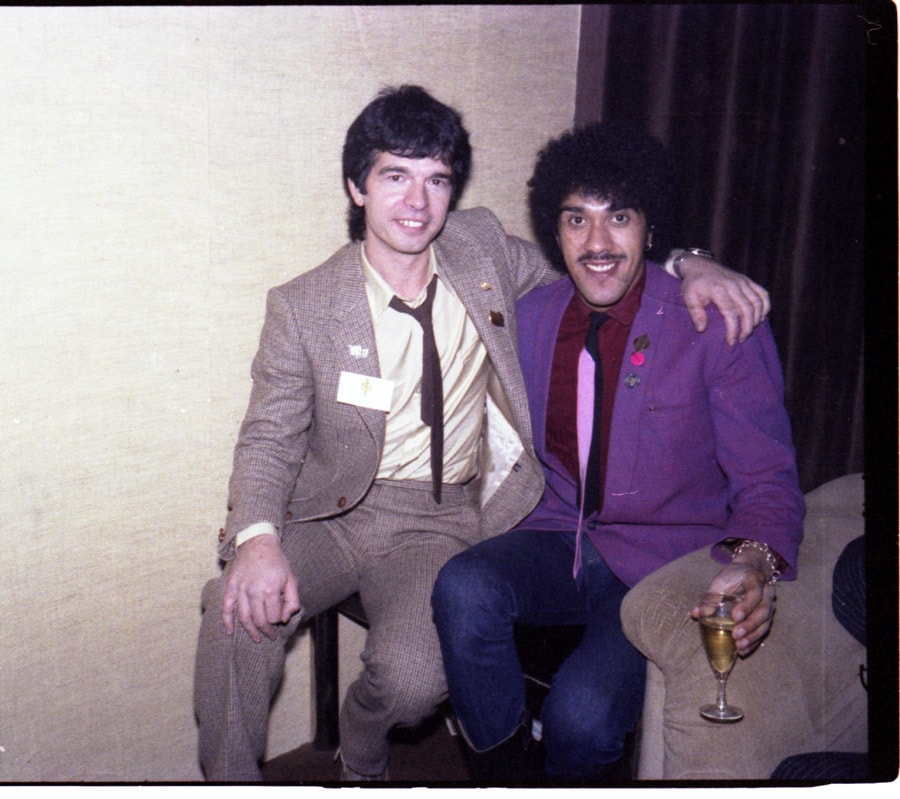

Tony Visconti and David Bowie in Hype.

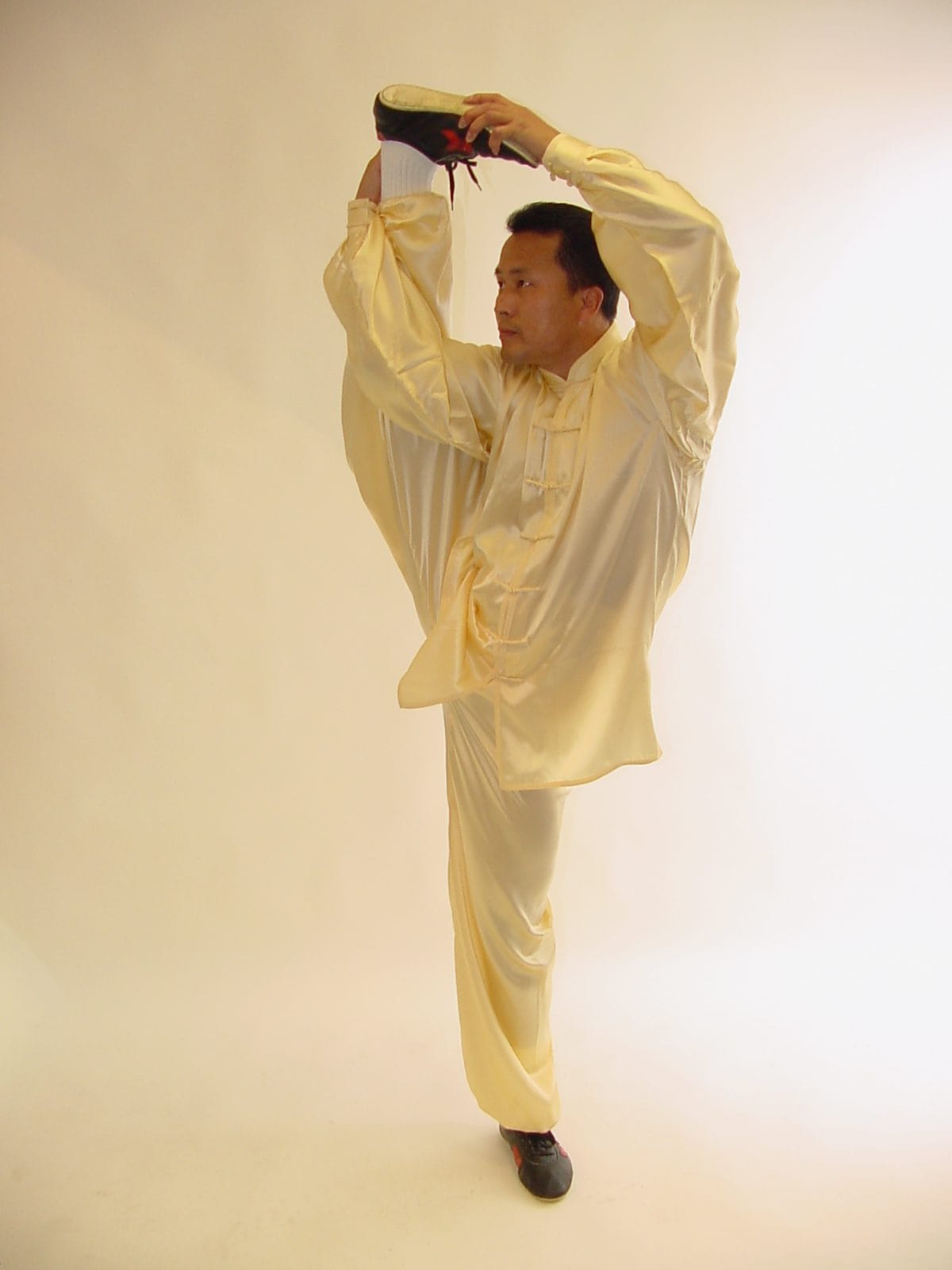

Tony Visconti: I have a low threshold of boredom. I can’t stay in the same genre for more than one album at a time. I like to switch it up. One of the most radical departures for me was working with Elaine Paige, the first lady of British musical theater (the first Griselda in Cats), recording reimagined show tunes. The executive producer was the composer Tim Rice. I looked forward to those four albums I made with her because I was working with the likes of Thin Lizzy and David Bowie and other Rock bands in those years. I also recorded Folk artists for the same reason. From practicing Taiji for decades I’ve learned to balance Yin and Yang. I must point out that I have to love the artist and their music in order to work for them. The money is the very last consideration. I stand by every artist and record I’ve produced for them. I love all forms of music.

Tony Visconti with Phil Lynott of Thin Lizzy.

J.S.: You are an accomplished multi instrumentalist, yet onstage you seem to prefer playing bass, including your recent Holy Holy tours with Woody Woodmansey. Sting has pointed out in the past that the bass player actually is able to control a band musically in a covert way (a “benign dictatorship”). Is bass a way for you to keep your producer’s hat on in a live setting, so to speak? What is it about the bass that has continually drawn you to it throughout your musical career?

T.V.: I started playing a stringed instrument at the age of 5, a ukulele my parents bought me for Christmas. I was singing and accompanying myself within days. As my body grew I stepped up to a baritone ukulele and then a family acoustic guitar that was festering in the corner of our living room for years. Its action was so high off the fretboard you could slice hardboiled eggs on it. But my parents recognized my perseverance and sent me to a great guitar teacher, Leon Block, when I was 11 and bought me a serious guitar. Then, in high school, I begged to play string bass in the orchestra. I never took a formal lesson, but the head of the music department at New Utrecht High School, Dr. Israel Silberman, took me under his wing and tutored me as much as he could and recommended bass exercise books from which I practiced like mad!

I would say that my guitar and bass chops are about equal. I naturally graduated to electric bass and that opened the world to session playing and playing in bands. There are about 40 would be guitarists to every 1 bass player so there was never a shortage of work for me. I had a drummer friend, Frank Steo, and we would jam, just the two of us for hours on end several days a week, Jazz mostly. That was a wonderful time for my development and I could sit in with Jazz players much older than me and hold my own. But my future seemed to be in the world of Pop and Rock. That’s when I discovered the power and importance of bass playing. What the composers of old always knew was that there were basically two melodies running simultaneously – the top melody played by any number of different instruments in a high register and the low melody played by the larger orchestral instruments. This is an empirical rule that applies to all forms of Western music.

I first started playing simple bass lines, like Boogie bass (on early Rock and Roll records) then more subtle bass parts that don’t necessarily have the root note of the chord at the bottom. That was a big adventure for the young me, that the third of the chord and even the flatted seventh could be in the bass line. Later on, after I moved to England, I was under the influence of bass players like Jack Bruce, who played lead bass with the dexterity of a guitar player. Being both a guitarist and bassist this came naturally to me. Mick Ronson persuaded me into playing in Bruce’s style for Bowie’s The Man Who Sold The World album.

J.S.: You played with Woody Woodmansey in a pre-Spiders From Mars band back in the UK. What was it like playing together again, and how did it feel to be touring now vs. gigs back in the day?

T.V.: I remember walking into the first rehearsal with Woody and Holy Holy in London. They weren’t expecting me that day (as I had just flown in from NYC) but a rental bass was waiting for me on a stand and plugged into an amp. I hadn’t seen Woody for years and they were playing a song when I walked in. Woody and I threw big grins at each other and without a second to think I picked up the bass, turned it up loud and started to play with the band. It was magic. What Woody and I had all those years ago was still there – only better! I have to say I had been practicing the songs we were going to play in the concerts every day for three months prior to this trip. It paid off.

J.S.: Electric Warrior and The Slider are records that actually received more acclaim for T.-Rex and Marc Bolan back in the early 1970s than any of your other productions at the time. Given that Bolan was playing mostly folk acoustic music prior to then, what were some of the conditions that contributed to the Electric Warrior T-Rex sound that put glam rock on the map? T-Rex live concerts did not quite have the same vibe as those records. Were there any studio or other parameters that helped you to capture or create that special magic? Have the anniversary re-mastered reissues given you sufficient opportunity to use modern technology to improve these records further, and if so, how?

T.V.: Modern technology has made these recordings more immediate and modern sounding. In the ’70s there was always a fear off putting too much low end on vinyl, that the tone arm might jump off the disk. I would take a full frequency mix to a mastering engineer who would promptly roll off the bottom end of the mixes. Such rules don’t apply today.

Marc Bolan and David Bowie used to come to my apartment in London when they were still living with their families, both were two years younger than me. I always had an acoustic and electric guitar and a bass openly available in my living room. Marc loved playing my Fender Stratocaster. Often the three of us would jam until just before the Underground shut down for the night. If not for that we’d play all night long.

Marc and I wanted to make hit records. We came so close when his duo was called Tyrannosaurus Rex. But the name change came, T. Rex! Marc wrote a little ditty on the electric guitar called “Ride A White Swan” that reached number 2 in the British Pop charts. Besides the addition of the electric guitar and electric bass (my Fender Precision that Marc borrowed and played) I also wrote a simple string line played by four violinists. T. Rex rapidly expanded to include a drummer, Bill Legend, and a bassist, Steve Currie, as well as Micky Finn, already on percussion. Suddenly our camp exploded with hit singles and albums over the next few years. String sections became a very important aspect of the T. Rex sound. Instead of lush “Mantovani” strings, I wrote jarring string parts with crunchy harmonies played by a new breed of string players who concentrated on playing perfectly on the beat and respecting the groove of the song.

From L to R: Audio Engineer Malcolm Toft, Tony Visconti, and Marc Bolan of T. Rex.

I must add that another important aspect of T.Rex was the falsetto backing vocals first sung by Flo and Eddie, formerly of The Turtles, but then in Frank Zappa’s band. When they were no longer available Marc and I took over the falsetto duties. It’s hard to tell us apart from Flo and Eddie, we actually fooled them.

The other aspect was the way I developed a bunch of mixing techniques for the T. Rex sound. I’ll make no secret that I learned all of this from The Beatles recordings, the very reason why I moved to England, to learn the techniques employed by George Martin and Geoff Emerick. But with T.Rex there definitely was a new sound in the world and then other groups started to imitate us.

J.S.: Your “3 Mic Technique” used for David Bowie’s vocals on Heroes has become a favorite one immediately associated with your name among producers and engineers. Do you think there are other aspects of your engineering and producing skills that you would prefer people were aware of, even if the record(s) that you used them on were not as well known?

T.V.: The 3 mic technique used on David Bowie’s Heroes album is well described in a YouTube video, I don’t want to go into the complexities here. The snare drum sound I made for the album Low by Bowie using an Eventide Harmonizer made an incredible impact at the time. I had the only one in London more than six months before anyone else and I experimented in my studio finding all sorts of new treatments for conventional sounds. It was extremely expensive to buy and that is probably why no other producers or studios ran out to buy one. They probably asked, “what would you need that for?” After the album was released my phone started ringing with many producers and engineers asking me how I did that. I wanted to hold on to my secret a bit longer, but actually I am always a bit wary of giving away my secrets so easily. I think only the people I work with have the right to know how I do something, as part of my team.

Brian Eno, who played a portable EMS Synthi A synthesizer on David Bowie’s album Low.

J.S.: During the 20+ years we have known each other, I’ve been aware of your passionate involvement with Chinese martial arts. Was this something that originated during your Brooklyn youth or later on in your life? Are there instances that you can cite where you think the martial arts training has helped you on a recording project with someone unfamiliar with martial arts? Conversely, how about with someone who was also a martial artist, like your fellow student of (Chen Taiji Master) Ren Guang Yi, the late Lou Reed?

Grandmaster Ren Guang Yi, Tony’s Chen Taiji teacher.

T.V.: This is a subject very close to my heart and difficult to explain to people who don’t practice martial arts. My curiosity was piqued by my 6th grade teacher, James Flanagan,who had served in the armed forces. He said there were men in Japan who could chop wood with their bare hands. But there was no way of finding out about this strange practice until a few years later when I understood he was talking about Karate. At 17 I was introduced to a teacher of Yun Mu Kwan, a Korean form of karate. His name was Min Pai and he was my teacher for at least two or three years. He was a blackbelt 1st degree and he had some very talented people in the school who never rose above brown belt. He explained he couldn’t promote anyone up to his degree, he’d have to go back to Korea to get a higher grading himself to make someone a blackbelt. But the discipline was good for me, as I was in danger of becoming a decadent musician.

Min Pai, Tony’s Yun Mu Kwan teacher.

Fast forward to my arrival in London. I worked hard and long hours in my first two years, no time for martial arts. Then Bruce Lee exploded on the screen and Chinese martial arts started to become popular. My studio in London was one block away from Chinatown. I met a Chinese Wing Chun practitioner whose father owned a restaurant. I had some space in my studio and we started an informal Wing Chun school. The main students were waiters from Chinatown. I was exposed to other Chinese styles, Hung Gar and Pak Mei mainly. I was going to midnight shows every weekend with my teacher watching action films from Hong Kong. I learned the first two Wing Chun forms and was starting the third one when my teacher mysteriously left town. But I had become aware of Taiji.

I found a great teacher, John Kells, who studied the Yang style in London and Taiwan for many years with a Dr. Chi, a student of Cheng Man Ching. Kells had incredible skills. His uprooting technique was astounding. We used to line up, run towards him one at a time and try to push him down. In a split second I would be flying through the air backwards and when my feet touched the ground I couldn’t stop the acceleration. There had to be someone catching me to avoid crashing into the wall. I studied with Master Kells for 5 years in the art of being soft, absorbing energy of an opponent, and deflecting their energy. I thought this was everything about Taiji.

When I returned to New York I practiced on my own. I went to several Yang style schools as an observer and I couldn’t find one that I liked. David Bowie later asked me if I was still practicing martial arts and I told him about my dilemma. He said I should phone Lou Reed, whom I already knew, and he could help me. I phoned Lou and he told me about Master Ren Guang-yi and that he was studying the Chen style of Taiji. This style was relatively unknown in London, I only saw line drawings of Chen moves. I’ll never forget Lou’s words about Master Ren, “He’s the real deal!” I spent about 12 years with the (now) Grandmaster Ren and learned even more eye opening facts about what Taiji is. The Chen family invented it in the 17 century, it is a fairly modern martial art. They were a family with a strong warrior tradition who escorted caravans through China’s Silk Road to Beijing as bodyguards. All styles of modern Taiji evolved from this one. Consequently there is an emphasis in two-person exercises and sparring at various degrees of safety constrictions. We’ve never killed each other. But there is also emphasis on serenity and moving meditation. This is a golden age for Westerners to learn martial arts from families who closely guarded their secrets for hundreds of years from other Chinese people.

For me, I have gained much confidence practicing Taiji. I am physically very healthy and my mind works quite well. Both Lou Reed and I worked in a world full of egotistical artists’ aggressive business traps. The Taiji way of thinking, the balance of Yin and Yang, the power of softness over hardness has helped us enormously for peaceful results when conflict is in our way.

[John Seetoo’s interview of Tony Visconti will conclude in Copper #97.]