Copper has an exchange program with FIDELITY magazine (and others), where we share articles, including this one, between publications.

That smell! Nothing compares! Old record sleeves, the dust of decades past.

While record stores are dying out at an alarming rate in this country, a very special culture of jazz bars and jazz cafés has survived in Japan in general and Tokyo in particular. Here, jazz fans can rummage deep into the past, pulling from the unfathomable depths of wall-sized shelves jazz records that most people didn’t even know existed. “Kissa” translates as “store where you drink tea,” the equivalent of the European [and American] “coffee shop.” The only difference is that jazz from the second half of the 20th century is rarely played in Starbucks and the likes – and certainly not as a concert of your choice.

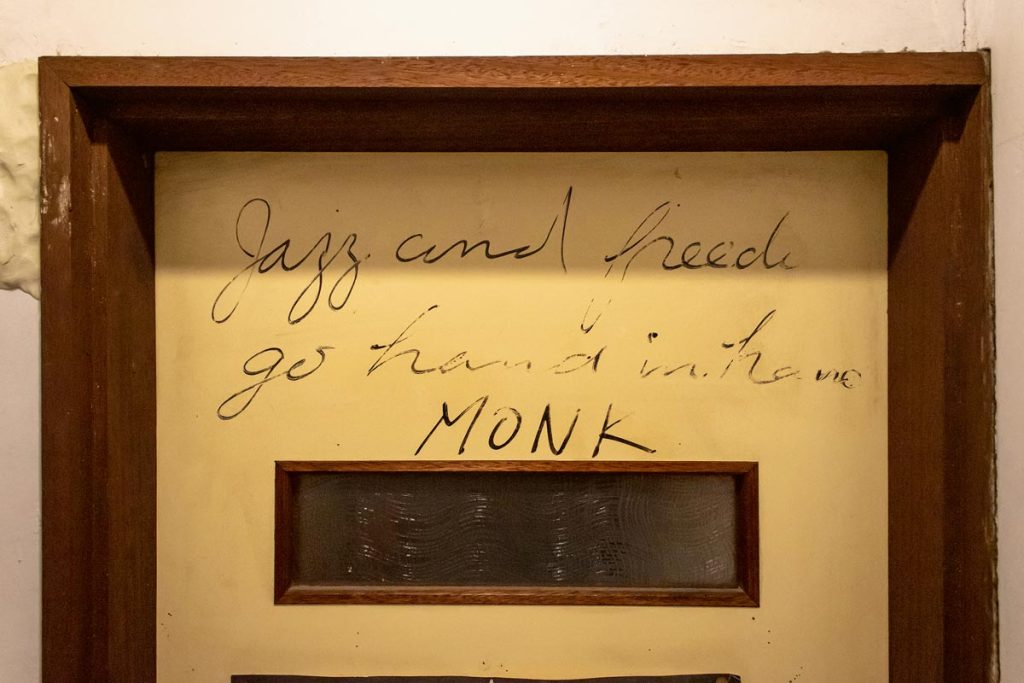

Documentary photographer Philip Arneill, who hails from Northern Ireland, has taken on this wonderful parallel world beyond the chaos and noise of Japanese beehive settlements, capturing these intimate kissas in very atmospheric images. Images that make you want to reach in and pull out a creased copy of John Coltrane’s Blue Train or Miles Davis’ Kind Of Blue and listen to them through ancient horn loudspeakers. “Japanese jazz pubs and cafés are insular worlds where time stands still,” reads the blurb on the lovingly-designed illustrated book published by Kehrer-Verlag.

In Tokyo, there are – as of yet – a large number of these “Jazu Kissas,” which are gradually beginning to die out because their customers or guests are slowly reaching an age at which their physical condition no longer allows them to combine a visit to the pub with the enjoyment of jazz. Arneill and [writer James] Catchpole have long since expanded the project, which began in 2015, beyond Tokyo and have documented a quintessentially Japanese phenomenon in Tokyo Jazz Joints, which also makes it clear how important jazz is, at least among the older generation.

The origins of jazz kissas date back to the time before the Second World War. After the War, they became increasingly popular and accepted by broader sections of society. The phenomenon reached its peak in the 1960s and 1970s. Since then, the curve has been pointing downwards again. Perhaps this is also because, although there is a vinyl renaissance, the musical tastes of those who are rediscovering the black disk for themselves, even in Japan, are hardly focused on an intellectual niche music called “jazz.”

When Philip Arneill describes how he first came into contact with the world of Kissa together with James Catchpole, his story speaks of respect, even awe: “It is a lively spring evening, clinging almost playfully to the last whisper of winter. Neither of us knows what to expect. We don’t really know each other either, apart from a few conversations shouted back and forth and handshakes on noisy club nights. We stand next to each other, full of expectation, in a drab station district on the southeastern edge of Tokyo. The pub is tucked away near the railroad tracks.

When we first went there, it was closed, but today the door latch is open. From the outside, it’s hard to tell what’s behind this door, only the beautifully made pub sign screwed to the wall with Japanese and Latin letters gives a clue. I head for the narrow staircase covered with a rough carpet. The faded burgundy steps contrast with the blue and gray of the walls. At the top there is a large photo of Miles Davis on the floor, right next to crates of empty bottles.”