Imagine your ship is sinking, your fate is sealed, your life is doomed, and yet you remain calm and of service to others – not over the course of seconds like during a flight disaster, but over the course of hours.

As you watch the last lifeboat being lowered into the water, you don’t force your way onboard or scramble for some floatation device. Instead, you resign yourself to martyrdom because you know your music is mitigating the terror of the remaining passengers.

That’s the selfless courage of the eight young men who formed the band on the Titanic. I always thought these heroes deserved their own movie.

While watching the 1953 version of the film on our 21-inch black and white TV with my family, I was sure I’d panic like most of the passengers. I could easily visualize climbing over people on the stairways to get onto the deck, scrambling around for the next available lifeboat, and fighting for a spot on board to the exclusion of others.

This was in direct conflict with my religious indoctrination, which taught that we must do the right thing at all times or face terrible consequences. The movie convinced me I wasn’t the child I should be. I felt ashamed and unworthy of heaven.

The musicians in the Titanic's band. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/public domain.

I had recurring nightmares of St. Peter at the Pearly Gates chronicling my cowardice to a gallery of white-robed angels. At some point, they extended their arms towards me, thumbs down, and I was marched off to the pyrotechnic basement of mother rapers, father stabbers, and child molesters.

Two decades later on a hot summer evening, I shared this nightmare with fellow kibbutz volunteers at a disco in Tiberias, Israel. That started a lively philosophical discussion at our table. Varying opinions were expressed – mostly castigating the pomposity of the angels.

Someone suggested, “Well, Montana, we’re on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. Why don’t you try to walk across? If you succeed, you’ll have evidence of God’s favor. It’s been done before, you know!"

For some reason, that seemed rational. As I wandered down the pier, half the disco patrons followed to watch the spectacle. I descended the steel ladder fully dressed and full of hope, stepped onto the surface of the water, and sank like a sinner.

Somebody shouted, “Get thee behind me Newton!" The whole crowd broke out laughing. Many of them jumped into the water with me in a show of solidarity – or maybe because they were overheated from the dancing.

Courtesy of Pexels.com/Anselme Courau.

Dripping wet, we all sat on the pier afterwards listening to “Hotel California” from the disco and consuming whatever substances were being passed around.

At some point that evening, I experienced a mind-blowing hallucination. It dawned on me that I'm made of the same stuff as the Sea of Galilee. Even if my body was crushed like a beer can, my essence would always find its way back to the sea. I was reminded of the words of Kahlil Gibran: “...life and death are one, even as the river and the sea are one.”

I scrutinized my childhood teachings. If God admits only saints into heaven, it'll be a sparse reception. Surely less than 0.1 percent of the earth’s population would qualify; the other 99.9 percent is bound to end up in the pyrotechnic basement.

Why would any loving father doom 99.9 percent of his children to eternal damnation? What equitable judge expects people to act like saints – any more than he’d expect cats to act like dogs? Who deserves such excessive punishment for sins committed in ignorance? I determined that a just God would never do that.

Maybe His goal is to send everyone to the appropriate place; heaven for pious people and the pyrotechnic disco for party people? He probably knows that mixing them in the same afterlife would be hell for both.

So, after He blesses the wine upstairs and conducts Mass, He changes out of his white robes into his cutoffs to join us downstairs. When He arrives, He grabs a beer and snatches the mike to announce, “Hey party people, all that stuff about hell was only a myth to impel you to treat each other right! Some of you seemed to need that.”

Just before He fires up the pyrotechnics and the music he proclaims, “All right now, drinks are on the house, so everybody wang chung tonight!” Isn’t that what a loving father would do?

Or is this whole concept of a Heavenly Father just a reflection of humanity’s desire to anthropomorphize anything it doesn't understand? The Buddha wrote, “Our theories of the eternal are as valuable as those a chick still in the egg might form of the outside world.”

That’s the last thought I remember from that night. The next day, I woke up in an unfamiliar place.

“How are you feeling today?” the guy who walked into the room asked with a smile. I recognized his face from the day before, but couldn’t place him.

“Ronen!” he re-introduced himself, "I'm the disc jockey, remember?”

“Ah yes, you sat at our table for a while.”

“Right, when they fished you out of the water, they brought you to my cabin because it’s closest. The others said it looked like you tried to drown yourself?”

“No no, well, I don’t know,” I mumbled; "I just wanted to swim to the other side.”

“Let me get you some breakfast man.”

Now I was confused. Had the thought of dying actually seemed attractive last night? At the time, I was convinced that death is just a transition, like stepping from the Jacuzzi into the pool. Was that a revelation from a greater intelligence, or was it the drugs talking?

A quote from the Coptic Gospel of Thomas came to mind: “Have you discovered the beginning so that you can look for the end, because the end will be where the beginning is.” This finally made sense to me – death is nothing more than going back from whence we came?

Ronen set down a plate of eggs, lox, toast, and coffee. “So if you wanted to die, why are you still here?” he asked.

I paused while munching…“If I was dead, I wouldn't be able to enjoy this delicious lox.” He laughed heartily.

“Perhaps the purpose of life is simply to experience it,” he proposed, “like a vacation.”

“How can anyone enjoy a vacation if they’re worried about what happens afterwards?” I asked. “Doesn’t that take all the joy out of it?”

“Good point; perhaps religion is a barrier, rather than a route, to enlightenment.”

“Perhaps enlightenment can’t be taught, it must be experienced?” I added, “Christ said, ‘Except ye become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.’”

“Children are always on vacation,” he agreed. “They don’t worry about an afterlife, they experience life moment by moment. Maybe that’s the lesson.”

You’re right. Ronen, Christ said as much: “Take therefore no thought for the morrow, for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself.”

Ronen pointed to a poster on his wall with a picture of the Buddha which read, “The secret of health for both mind and body is not to mourn for the past, nor to worry about the future, but to live the present moment wisely and earnestly.”

“Ever heard of the Titanic?,” I asked. “Of course,” he responded.

“Why do you think the musicians kept playing as the ship went down instead of scrambling for their lives?”

He thought for a moment. “It’s better to perish playing than panicking.”

“Exactly,” I enthused, “We’re all sentenced to die from the day we're born. Life isn’t a journey; we shouldn’t focus on a destination. It’s a concert, we should enjoy every note before the ship sinks.”

“Maybe the Titanic’s musicians knew that,” he responded. “My uncle worked all his life to get rich, but died before he had time to play.”

“It’s no better being a slave to one’s cravings than it is to one’s dogma,” I postulated; “They both detach us from the present moment.”

He quoted Einstein: “Yesterday is relative, tomorrow is speculative, today is electric; that’s why they call it current.”

I added, “Perhaps the Biblical reference to ‘wailing and gnashing of teeth' in the afterlife is frustration over failing to live life in the current moment while we had the chance. Once it’s gone, it’s gone forever.”

We sat over the kitchen table all morning exploring such concepts.

Two weeks later, Ronen was killed by a bomb while traveling near the Lebanese border. I was devastated. The month prior, I’d ridden that same bus to ski the Golan Heights.

After I adjusted to the shock, I got to thinking: the notion of security is an illusion – we have none. Ronen could as easily have died from an illness, a natural disaster, or a needless accident. Regardless of the planning, work, and sacrifice we invest in controlling our future, we are always at the mercy of fate.

Shortly afterwards, I was on a plane out of Tel Aviv.

The experiences in Tiberias changed my life. I never again sacrificed the present for the future.

When I got back home, I quit being a professional achiever, sold everything I had, rode my motorcycle to Southern California, and focused on wine, women, and song. When that got old, I found a woman who shared my passions for cocktails, camping, and camaraderie, and we spent decades riding the Sierras and the Rockies together – but that’s another story.

Some relatives didn’t understand my new lifestyle and wrote that I was “wasting my life on frivolity.” They reminded me of a quote from Friedrich Nietzsche: “…the dancers were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.”

I wrote back, “If I don’t dance to the beat of my own drummer, I’ll lose the desire to dance at all.” At the time, they objected, but 40 years later, most of them agree.

One of them sent me this quote from the Greek philosopher, Epictetus: “All belief systems must be tolerated...for everyone must get to heaven in their own way.”

Titanic musicians' memorial, Southampton, England. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Marek.69.

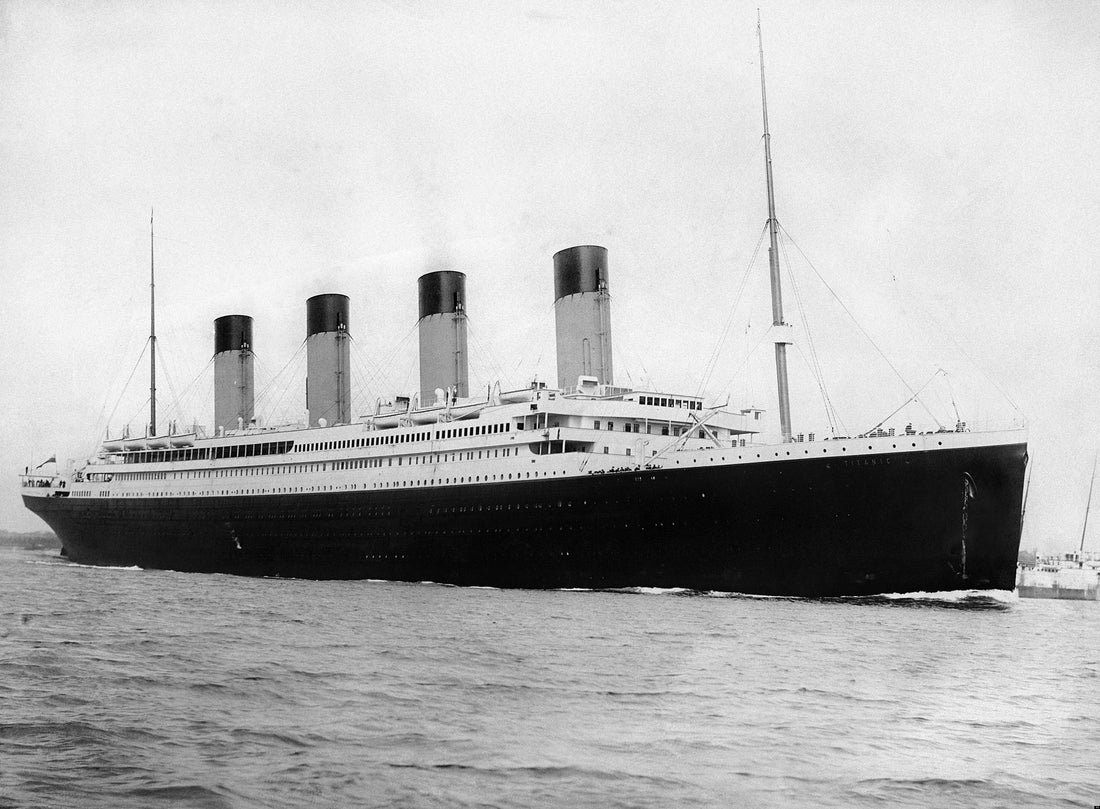

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Francis Godolphin Osbourne Stuart/public domain.