In the days before digital music, the primary medium for sound reproduction was vinyl records. Sure, there were some who preferred reel-to-reel tapes, but they were in the minority. The turntable was king, and it had to be properly set up. Any audiophile worth his (or her) salt owned at least one or two test records specifically designed for that task.

Over the years, I’ve collected a disproportionate number of such discs (it helped that I worked in record stores for much of my adult life, so I could obtain the ones I wanted at reasonable prices).

In the first part of this series (in Issue 205), the focus was on test records issued by record labels themselves. In Part Two (in Issue 206), albums from phono cartridge manufacturers were featured. Part Three (in Issue 207) looked at records issued by speaker companies. This time, LPs from publications are included, along with one from Radio Shack.

Project 3/Popular Science Stereo Test Record (1967)

Project 3 Records was a label with audiophile aspirations. It was founded by Enoch Light, a classically trained violinist, bandleader, and recording engineer. His musical career began in the 1930s. Some years later, he produced albums for one of the first quality-conscious labels, Command Records. His initial release for Command, Persuasive Percussion, was a best-seller, loaded with stereo effects that came to be known as “ping-pong” recording, with instruments bouncing back and forth between the left and right channels. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, people used these recordings to show off the separation of their stereo system with little regard for a more natural soundstage. Another innovation of his was the use of 35mm magnetic film (as opposed to conventional tape), offering higher fidelity. He was also a pioneer in the introduction of the gatefold sleeve, necessitated by his interest in providing the technical aspects of recording which led him to include extensive notes about the equipment and techniques used.

Project 3 (subtitled “Total Sound Stereo”) came about as a joint venture with the Singer Corporation (yes, the sewing machine company). Performing under the name Enoch Light and the Light Brigade, Light issued a series of big-band albums that meticulously copied the arrangements of some of the classic acts of the swing era. Many of his musicians were alumni of the most popular outfits back in the day.

This test album was a collaboration between Project 3 and the magazine Popular Science Monthly. Billed as “the complete test record,” it featured typical test tones and system evaluation tracks on Side One along with musical selections from the Project 3 catalogue on Side Two. The LP’s label featured strobe patterns for checking turntable speed at 33-1/3 and 45 RPM. The entire inside of the gatefold cover is taken up with detailed descriptions of the tracks.

The technical notes for this album are as follows: “The single frequency test signals on this record were recorded using the RIAA recording characteristic. The test frequencies were fed directly into the recording amplifier. The standard reference level used was 9cm/sec peak velocity at 1000 Hertz. The accuracy of the standard frequencies of 1,000 Hz and 440 Hz was calibrated using a Hewlett Packard 5214L counter. The master was cut in a controlled atmosphere on a Neumann 32G lathe utilizing a Westrex 3D recorder. A basic pitch of 200 lines/inch was used. However, a pitch of 12-1/2 lines/inch was required for the low frequency tracking test. The fourth passage of the high frequency tracking test contains stylus velocities exceeding 25 cm/sec.” (Have your eyes glazed over yet? …and that’s just the little blurb in the lower left corner!)

Stereo Review’s Test Records for Home and Laboratory Use Model 211 (1963) and Model SR12 (1969)

Back before the advent of subjective-listening-based publications such as Stereophile and The Absolute Sound, hi-fi aficionados turned to magazines like Stereo Review or Audio for information and technical evaluation of components and speakers. The reviews were focused mainly on measuring and reporting on frequency response, harmonic and intermodulation distortion, channel separation, and the like. For turntable reviews, wow, flutter, and rumble were the parameters under test. Rarely was heard a discouraging (or any) word about sound quality. The inference to be gleaned from such reviews was that the better the numbers were, the better the piece of equipment under review would sound.

It is therefore completely logical that these test LPs primarily featured test tones, balance and separation tests, along with cuts intended to evaluate cartridge tracking ability. Test Record 211 does have a couple of musical selections on Side Two, but Test Record SR12 has none. Both albums included a thorough booklet of instructions that went far beyond the technical notes on the Project 3 record.

I think these days we’d all agree that there are other (not necessarily quantifiable) factors influencing the sound of systems.

Stereo Review’s Binaural Demonstration Record (1970)

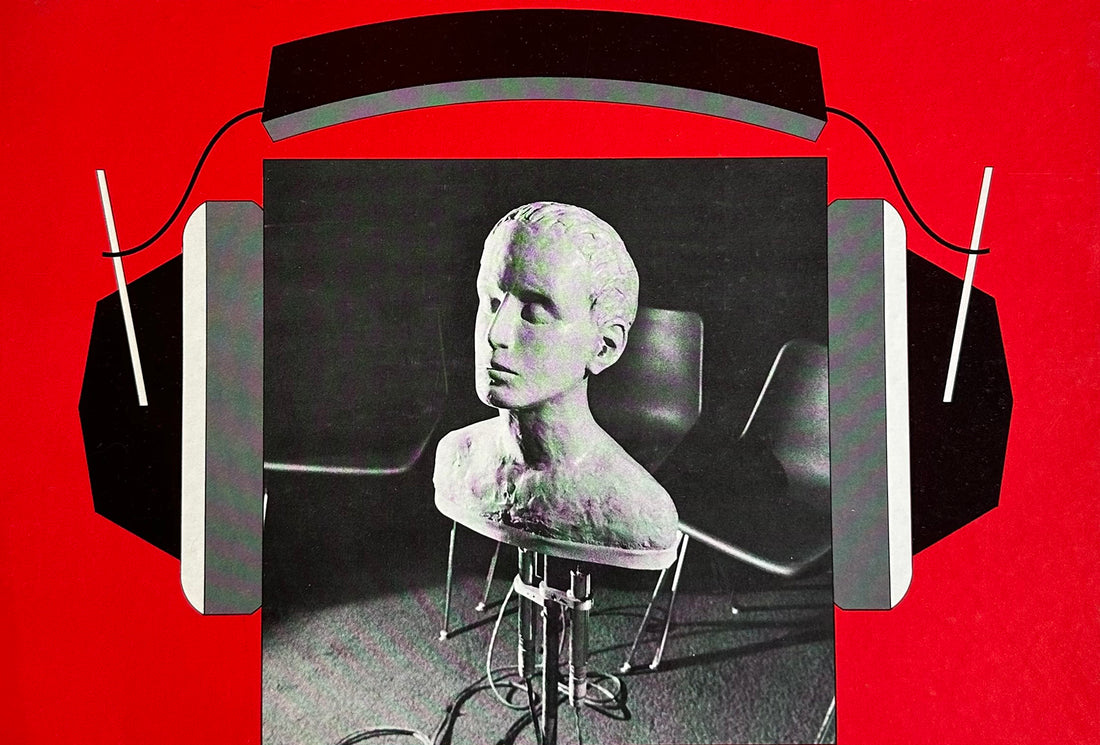

The magazine released this album to show off the spatial characteristics of binaural (“dummy head”) recording. As seen on the cover, a literal dummy head is fitted with microphones where the ear canals would be. Designed to be reproduced through headphones, binaural recording puts the listener in the field of sound as though you were in the place where the sounds were made.

Side One presents a wide range of sonic environments, such as city street sounds, a basketball game, a bird house at a zoo, a steel-manufacturing plant, and a parade with a marching band. Side Two features rock, jazz, and classical musical selections recorded in churches and college performing venues. The soundstage is indeed remarkable when heard through quality headphones.

The notes included with the album explain that “Max,” the dummy head, was cast from a clay model of an “average” human head. “Max underwent surgery to make the top of his head removable” to facilitate placement of the microphones at the proper position. It was also noted that, due to the impractical nature of carrying the dummy head and professional recording console in the field, most of the recordings were actually made with portable equipment, and in lieu of the dummy head for these tracks, the recording technician actually wore tiny capacitor microphones taped to his head.

Realistic Stereo Test Record for Home & Laboratory Use (1963?)

Realistic in this case does not refer to sonic veracity, but rather the brand name that was used by Radio Shack. If the title sounds familiar, you are not imagining things. This is simply a re-packaging of the Stereo Review Model 211 album. Sides One and Two are exactly as done on that previous LP. Aside from the artwork, the only differences on the cover and label are the use of an ampersand (&) in place of the word “and,” and the notation “Produced by Stereo Review Magazine for Realistic.” Even the included booklet is identical (with the addition of the word HIFI) to the Stereo Review version, with no mention of Realistic or Radio Shack.

The next installment in this series will feature test and demo records from a variety of sources, including a couple of albums that weren’t even meant to be played!