In my previous articles, I have alluded to the fact that there are many factors that determine the sound quality of an LP. The quality of the original recording is of course an important factor, but in my experience, different releases of the same recording on LP can sound very different, and even individual LPs within the same release can sound different. This is because the act of cutting what has been recorded on tape (or digital file) onto lacquer often involves compromises, and the priorities of the mastering engineer, as well as his/her skill and experience will affect the end result. Many audiophiles believe that LPs should only be produced by an all-analog chain. I won’t get into an argument over this point, but only say that I have heard some absolutely fabulous LPs that were cut from digital materials, and of course, plenty of horrible-sounding LPs cut from analog sources.

The number of old recordings being reissued on LPs nowadays is truly staggering, and the few remaining mastering engineers still active, such as Kevin Gray, are even busier now than back in the heyday of LPs during the 1960s and 1970s. The number of new LP reissues is limited only by the availability of mastering engineers, lacquer disks and record presses, as the demand seems insatiable. This is surprising, since there are still probably billions of old LPs sitting in second hand stores and people’s homes. These new reissues are not cheap, starting at around $30, with some special editions aimed at audiophiles, such as Mobile Fidelity’s Ultradisc One-Step LPs, costing over $100 each. (My MoFi LPs were all made in the 1980s.)

I have already mentioned the Electric Recording Company (ERC) LPs (in a previous article), produced with a complete tube mastering chain from the 1950s, that now cost over $500 each. Many audiophiles swear by some of the new reissues, whereas many record collectors believe that only the original releases are worth having. This has kept prices high for old LPs, sometimes in the hundreds or even thousands of dollars. Some prominent bloggers and vloggers of both camps have become so adversarial towards each other that normal politesse and decorum have been thrown out of the window. You can search for some of these videos on YouTube. Who is correct? Record collectors and used-record dealers have an obvious financial incentive to sing the praises of rare old LPs, whereas people involved in the reissue business have the same motivation to do the opposite.

There are arguments to support both sides. The original releases were cut just after the master tapes had been freshly made, and magnetic tapes do deteriorate over time, especially some old formulations. Moreover, the original producers and artists would have been involved in the whole process of producing the original releases, potentially making the sound more “genuine.” Some audiophiles also prefer the sound of tube equipment, the primary reason given by the owner of ERC for his effort to restore and maintain his ancient equipment. On the other hand, it is hard to believe that technology has not improved in the last 50 years. Modern reissues are produced in much smaller quantities, with more care and attention to detail. They are often produced with audiophiles in mind, which might or might not be a good thing. In my experience, most of the time, a modern reissue LP remastered by one of the reputable engineers will sound better than a random original LP, but you can also find original LPs that beat the pants off the reissues if you look hard enough.

Contrary to popular belief, the initial full-price releases from the major labels are not necessarily better than the later mid-price or even budget-price reissues. I have many Decca Treasury reissues that sound better than the original SXLs, and the same is true for RCA Living Stereo and their Victrola reissues. The vaunted matrix number (the number etched into the black space between the record label), which collectors rely on for valuation, is not a reliable guide to sound quality either. The only sure way to know is to buy many copies of an LP and grade the quality of each by ear, or buy from a dealer that grades (and prices) the LPs they sell by sound quality, such as Better Records.

I have been into open-reel tapes for more than 20 years, initially as a means of making live recordings at a time when good digital recording equipment was expensive, and professional analog tape recorders were cheap. Now, it is the exact opposite. Over the years, I have got into the circle of tape enthusiasts and collectors, which is quite separate from the audiophile and record collector circles. The former are mostly people involved in the recording business, usually ex-engineers, who have built up a collection of master tapes. The provenance of the tapes is very important. The original session tapes (edited work parts) are rarely available, since the studios tend to hold on to these zealously (or not so zealously, judging by what happened at Universal Studios). There are exceptions, and I know some people who have acquired the original masters from Westminster Records and Elite Recordings of New York, both of which made amazing-sounding recordings. Production masters, which are often directly copied from the original masters by the studios, are the next-best thing, but they are hard to come by as well. The studios also made safety masters, which are basically back-up copies, usually from the original master or the production master. These are also of the highest quality, and multiple copies usually exist. Some of these were disposed of when the labels digitalized their archives, usually taken home by employees and then finding their way into collections.

The labels have sent many distribution copies over the years to mastering studios around the world, and these have sometimes found their way to eBay and the like. Many of these came from Eastern European countries. Jugoton in the former Yugoslavia, for example, licensed many recordings from the West for release in the Eastern Bloc, and the tape library got disbursed during the dissolution of the former Communist country. I also know someone who acquired a large collection from the state-owned studio in former East Germany. The collection contained a large number of releases from Deutsche Grammophon between the 1950s and 1970s, and many Decca recordings as well. Melodiya in Russia also represents a rich source of high-quality recordings, and many of these were released in the West by EMI.

Depending on how many times these distribution masters have been used for mastering, some of these tapes might be quite worn. Copies that were professionally made by the labels or mastering studios usually lose very little in terms of sound quality, and even fourth- or fifth-generation tapes can sound amazing, especially when compared to LPs, which require many more steps during the production process.

Starting from the early 1970s, many master tapes were Dolby encoded. In my experience, these tapes tend to lose a bit of transparency compared to the earlier tapes, but this could also be due to the early transistor equipment of the era. I tend to prefer early stereo tapes made with tube equipment from the late 1950s to the late 1960s.

Commercial pre-recorded open reel tapes were available from the early 1950s until the mid-1970s, when the compact cassette tape took over, but they were always niche items and expensive back in those days. I have seen pre-recorded tapes in 15 ips format released by several specialized Japanese labels as late as the early 1980s. The Tape Project managed to reach agreement with several music labels to release tape copies in the early 2000s and started a trend. There are now several legitimate sources for high quality pre-recorded tapes from the major labels, as well as more than a dozen smaller labels that are releasing tapes of their own recordings. The quality of these tapes tend to be more consistent than reissue LPs, since directly copying master tapes is more straightforward than remastering LPs. It is just a matter of making sure the machines and the source tapes are in top condition. Some major labels, notably Decca and Mercury, are still reluctant to license their recordings for fear of piracy, even though it is far easier to copy a digital file or even an SACD.

Audiophiles who are serious about analog sound really should experience the sound of master tapes, for this represents the ultimate level of sound quality possible. Yes, the cost is high, but as a group, audiophiles are not known to be shy about spending money, even on things that are of dubious utility. Cables, no matter the cost, cannot reduce the distortion and the compression inherent on your LPs. Most people don’t realize their LPs sound compressed or distorted until they hear the original recording on tape. I have heard comments such as, “why on earth did HP put this recording on his Super Disc LP list?” This is because the LP of the recording you have heard does not do justice to the recording! Therefore, I would like to reevaluate the merits of some famous recordings by going straight to the source.

Granted, even if the tape sounds good, it does not mean you will be able to find an LP that sounds good, because in some cases, it is just extremely difficult to make a good LP. Some classical works are of a length that is practically impossible to fit onto one side of an LP without compromising the sound. The solution would be to chop the piece or the movement into two, but this is obviously unsatisfactory from a musical point of view. This is the most obvious advantage of digital. With tape, I can fit 33 minutes onto a 10-1/2-inch reel at 15 ips, which is usually sufficient for classical music, or 48 minutes if I use thin tape or a 12-inch reel when necessary. The thinner tape might lose about 1 dB in signal to noise ratio, and has a higher risk of stretching and print through, but the tradeoff is very small.

In my last article (Issue 164), I mentioned a new source for legitimate tape copies of EMI recordings. The Italian magazine Audiophile Sound (http://www.audiofileshop.com/en/) is releasing three EMI recordings on tape, and I have already discussed the mono Callas recording. The other two are stereo recordings. Here is some information on these tapes, which was provided by the magazine’s editor, Pierre Buldoc.

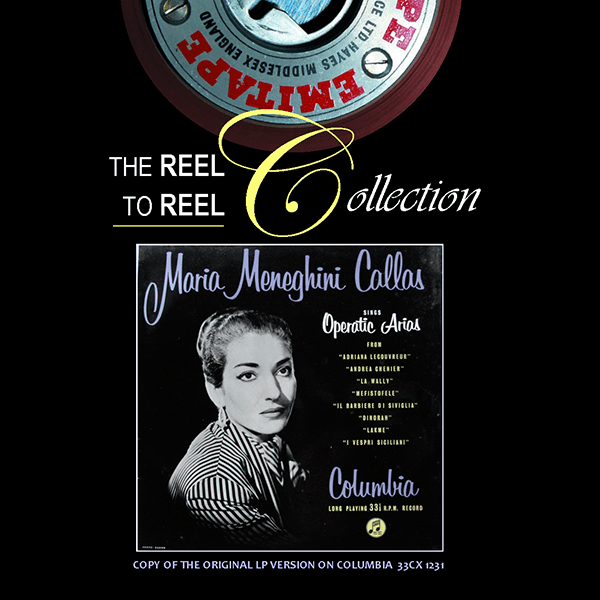

Maria Meneghini Callas Sings Operatic Arias, Audiophile Sound reel-to-reel tape cover.

“As far as the three titles are concerned, the masters are all on 1/4-inch tape. Abbey Road [Studios], using a Studer A80, duplicates for us, [with] flat [EQ] and back-to-back, the original masters (edited work parts on 1/4-inch tape) onto another Studer A80, this time, however, equipped with 1/2-inch tape heads. Like this, we lose very little in the making of our production master, maybe 1 dB. The production master on 1/2-inch tape therefore becomes our master and is then played back on an Ampex ATR 102 which then sends the signal straight to the duplicating recorder, another Studer A 80, this time modified by the late Tim de Paravicini. Cabling is all by Yamamura.”

There is a choice of copying the recordings onto the RTM (Recording the Masters brand) SM900 studio mastering tape, or their thinner LPR90 long-play tape, which will save a little bit of money and space. The customer can also choose between IEC/CCIR or NAB equalization. For 15 ips, I prefer IEC/CCIR.

I can verify that the tapes are of very low generation, since the tape hiss is extremely low even for the ancient Callas recording, and the sound is very transparent. Based on my descriptions above, the tapes that customers receive are of a lower generation that what was normally used for cutting lacquers in the old days.

Image from catalog included with Maria Meneghini Callas Sings Operatic Arias. Courtesy of International Audiophile Recording Ltd, UK.

I want to add a bit of information about the Callas tape. The recording was made in September 1954 at Watford Town Hall, an excellent recording venue. It was made on a ¼-inch one-track recorder running at 30 ips. The higher speed tends to limit low-frequency extension, but this is not a problem for the soprano voice. Having re-listened since my last article, I can confirm that the sound is very transparent, with excellent presence and impressive dynamics.

Maria Callas and Giovanni Battista Meneghini, her husband and manager.

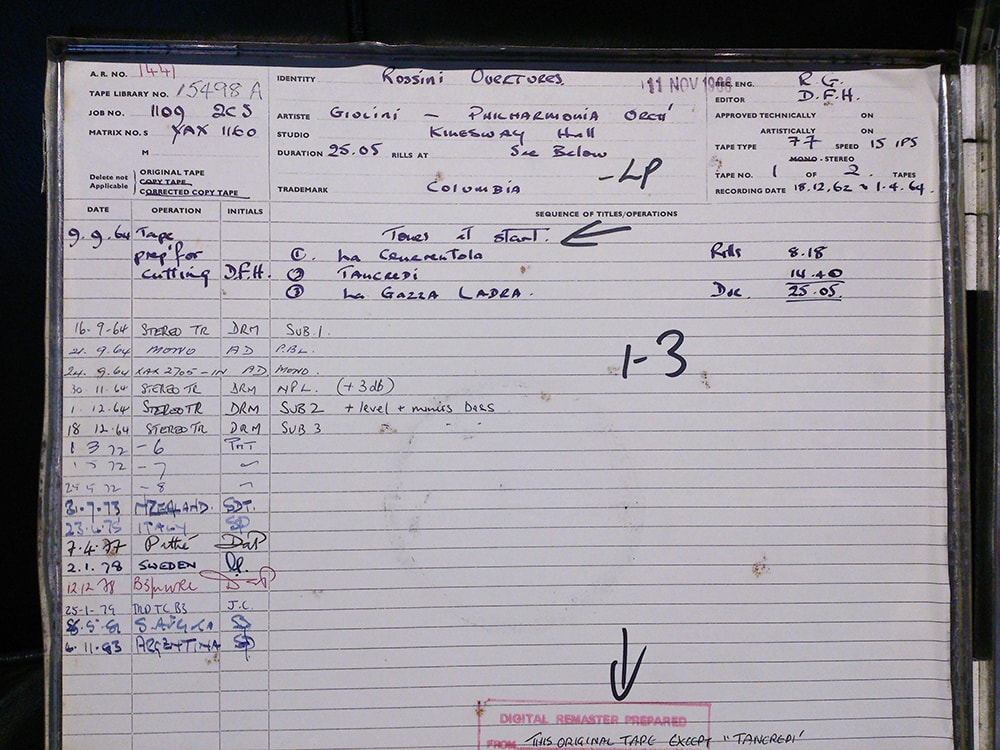

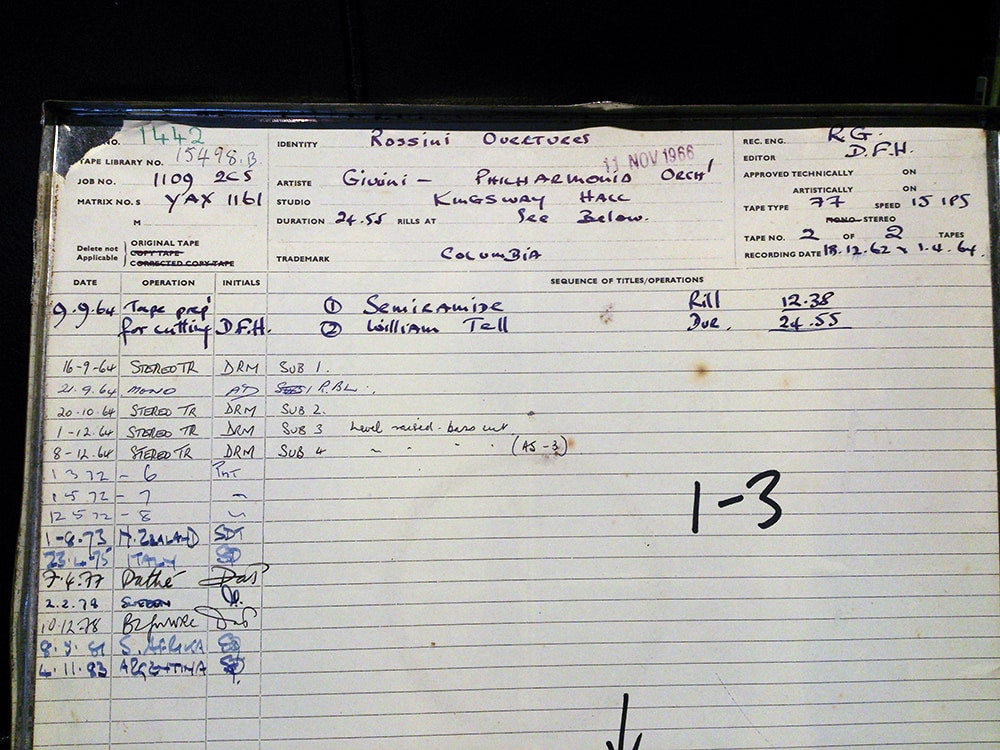

The other two currently-available titles are in stereo. The Rossini Overtures with Carlo Maria Giulini conducting London’s Philhamonia Orchestra is not a well-known recording, and there is only one modern reissue on 45 rpm LPs. The recording was made in 1962 and 1964 at Kingsway Hall by Douglas Larter on 1/4-inch tape running at 15 ips and the LP was first issued on SAX2560 in 1965. The most famous Rossini overtures recording is the Decca SXL2266 with Pierino Gamba conducting the London Symphony Orchestra, and these two recordings have three pieces in common, including The Thieving Magpie, the William Tell Overture, and Semiramide. The other two pieces on the EMI tape are Tancredi and Cinderella. The sound of the EMI tape is very transparent with lovely highs and impressive dynamics. However, the low end is a bit anemic compared to the many Decca Kingsway Hall recordings I am familiar with. This gives the overall sound a more lightweight presentation. The depth of the soundstage also seems a bit flatter than the best Decca recordings.

Rossini Overtures, Audiophile Sound reel-to-reel tape cover.

I examined several more EMI tapes from different sources and I can confirm the general impression that the EMI sound is flatter and more lightweight than that of Decca (or Mercury for that matter). I wonder if this was deliberate, since the Kingsway Hall acoustics were very favorable for the low frequencies. This presentation in no way detracts from the enjoyment of the recording, and in fact works well with this music, where excessive low frequencies can make the music sound heavy and ponderous. The performance is incisive and idiomatic, as one would expect from this brilliant maestro. The Philharmonia was considered one of the best orchestras in the world at that time, and this is clearly evident in this recording. The Gamba recording was made in Walthamstow Town Hall, another great venue, by the celebrated Kenneth Wilkinson. I do not have a tape of this recording, and I prefer the sound of the EMI tape to my Speakers Corner-reissued Gamba LP, which has distortions in several places.

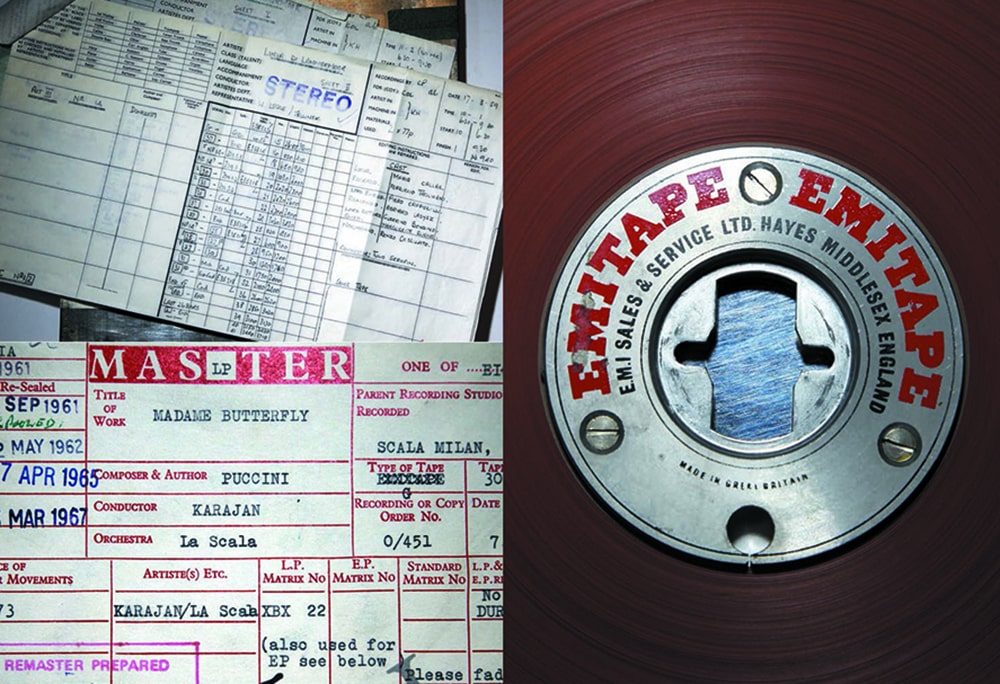

Above: original tape boxes for Rossini Overtures. Courtesy of International Audiophile Recording Ltd, UK.

The other stereo tape is the famous Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli recording of the Ravel Piano concerto in G and the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto. No. 4 The original recording was made at Abbey Road’s Studio One in 1957 by Christopher Parker, widely considered the best recording engineer at EMI. Mysterious and aristocratic, Michelangeli was as elusive as he was brilliant. His public performances were infrequent, and he was known for cancelling concerts. He did not make many studio recordings, and much of his discography comes from live concerts and broadcasts. The original LP (ASD255) of this recording is rare and expensive, and you should expect to pay at least $200 for a decent example. I have the SXLP reissue from 1974, which some listeners find preferable to the original ASD, but I find the sound quality nothing to write home about. The tape is something else altogether. It has a fuller and warmer low end than the Rossini recording, with the transparency and tonal qualities I usually associate with recordings from the vacuum tube era.

Michelangeli, Rachmaninoff Concerto No. 4 in G Minor and Ravel Concerto in G Major reel-to-reel tape cover.

This recording leaves one in no doubt of Michelangeli’s technical prowess (he was Maurizio Pollini’s teacher, after all), as the Rachmaninoff concerto is very difficult indeed, but it is the delicacy and elegance of his playing that fully reflect his aristocratic disposition. Rachmaninoff’s second and third piano concertos are far more frequently performed and recorded, but Michelangeli was a great champion of the Fourth, and with good reason. In his hands and under the baton of Ettore Gracis, there is a great deal of excitement as well as the composer’s trademark romanticism. After hearing this performance, one cannot but be convinced of its place in the pantheon of great concertos.

The Ravel Piano Concerto in G is one of my favorite pieces (as are most Ravel compositions). The opening movement never sounds rushed or frenzied, as it can be under the hands of lesser mortals. Control is perfect throughout, the phrasing and rubato as natural as breathing and never sounding forced or contrived. The master’s use of subtle micro-dynamic contrasts are best reflected on tape, as I find some of the finer details are obscured in the LP. The adagio movement is some of the most beautiful music ever written, and on first listening, Michelangeli’s playing can sound surprisingly cool. The reason is because he never makes abrupt changes in dynamics and tempo, or takes excessive liberty with rubato. However, it takes intent listening to bring out the subtle and refined shaping of the phrases and the fine dynamic shading that make the experience utterly mesmerizing. And I always find myself listening much more intently while playing tape, perhaps because there is just so much more detail than any other medium. This experience reminds me of the last time I heard this piece performed live at a concert in France with Jean-Yves Thibaudet on the piano, and I was transported once more to the venue, which was the Chateau de Clos de Vougeot in Burgundy.

The jazz-inspired final movement is full of excitement, and Michelangeli shows that he can do excitement as well as anyone. The long, sweeping runs are executed with laser-like precision and clarity, and again, nothing sounds hurried or frenzied. After listening to this performance, I can understand why he has a god-like aura amongst pianists.

The cost is 200 Euros for each album, which is a considerable sum when one can get a reissued LP for one-fifth the price. On the other hand, the tape is guaranteed to sound closer to the original performance than any other medium, including the original LP, which sells for far more in the case of the Michelangeli. And for me, time is the most valuable commodity, so why waste it on inferior-sounding LPs when something better is available?

Custom EQ50 tube equalizers at Abbey Road Studios, used in the production of the Audiophile Sound reissues. Courtesy of International Audiophile Recording Ltd, UK.

Header image: Maria Callas in 1960, photo © by Ken Veeder, courtesy of International Audiophile Recording Ltd, UK.