A 1986 interview for the Kinks' overlooked Think Visual

I was delighted to find the printed Q&A from an interview I did with forever-Kinks leader Ray Davies in 1986. For those of you who are new here or just coming back, newspapers and magazines rarely ran question-and-answer interviews in those days. We used the Q&As as the structure of a feature story.

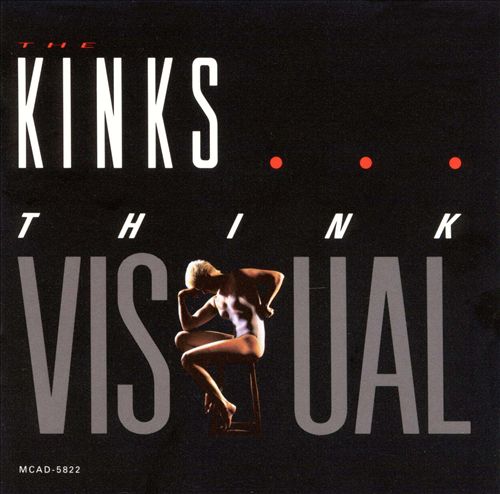

My problem now was trying to remember what Kinks album Davies was promoting. The folder just said, "Ray Davies/1986." I checked the Billboard Top 200 Albums list and found the Kinks' Nov. 1986 release Think Visual, their debut for MCA after a successful run at Arista, never got beyond No. 81 on the chart.

I called my friend and colleague Tom Kitts, author of Not Like Everybody Else, an academic biography of Davies. He sent me over a paper he had done called Think Visual: The Kinks vs. the Music Industry, from the journal Popular Music and Society (Routledge) published online Dec. 12, 2006.

Ray Davies, mid-1980s. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Yves Lorson.

Kitts wrote: "While Think Visual is a strong album, musically and thematically, it is a dark record, a subtle concept album about one of Ray Davies’s favorite themes, the music industry and its effect on the performer." The title of the album seemed sarcastic to me. The record business was in the throes of its co-dependent relationship with cable channels MTV and VH1, and Kitts noted that none of the three videos Davies directed for songs from the album made it into rotation at those essential channels. Davies, he said, wanted to make videos for an audience, not a demographic. In the 1980s music biz, demographics were destiny.

I gave a fresh listen for the first time in more than 35 years to Think Visual, and the first thing I noticed on Spotify was how few people streamed anything on it. Songs that I liked, such as "Natural Gift," which is delivered in an almost Lou Reed deadpan, has 25,575 streams; "Working at the Factory," which Kitts sensibly interprets to be about the music business: "the corporations and the big combines/turned musicians into factory workers on assembly lines’’ with no ownership over their creations, a little over 53,000 streams. A half pence in relative royalties for the entire album. It has to be among the Kinks’ most overlooked albums. Not great, but good much of the time.

The Kinks’ song "Welcome to Sleazy Town" is about a midwestern American city (Kitts' research says Cleveland,), attempting to gentrify, and by doing so, losing some grit and danger, but also character and flavor. I was most likely working off an advance audio cassette of Think Visual when I met with Davies, but the consistent inconsistency of his career and that of the Kinks made for an easy conversation. In fact, known for his moodiness, Davies was surprisingly optimistic. And his observations about cultural and social moods seem as relevant today as they were then.

Wayne Robins: The album is about a culture reliant on videocassette machines.

Ray Davies: The whole thing with the song "The Video Shop," the reason I developed the story, is that the man in the shop gives the people much more than videos. His videos have a special quality to them that allows [people who watch them] to be better people. In other words, use the tools to your advantage, and don't become a zombie. Switch off the TV, and be selective. That's the good side. I think there's a tendency of people to become solitary.

WR: "Natural Gift" is very positive and uplifting, at least for a Ray Davies song.

RD: It is in a minor key.

WR: But it does reflect a certain optimism, or at least comfort?

RD: If you can spread optimism, that's the best disease to spread. The best, most positive thing is optimism. I guess negativity is too easy now, everybody's too worried now. Every day, there's some new crisis.

Humor is very important to me. I laugh a lot more than people imagine I do. I get a lot of fun out of watching people. I spend a lot of time watching and studying them. Going back to films, the films I do will be about people, the way they act. I'm very optimistic about people. It's just the machinery that bothers me.

WR: The corporate machinery.

RD: Yeah. People turning into their jobs.

WR: Doesn’t that happen with rock musicians too?

RD: I've seen it happen to a few people I've known. They become, they believe what they read in the papers, they become their image. I think everyone has the right to create their own image. If they want to believe it, that's fine. There comes a time when it will burn you out. It nearly happened with me. I caught a cold or something, got very sick, and while I was getting better I decided I would step out of it occasionally and look at it fresh. I've seen a lot of people get burned out and a few of them die as a result. Rock and roll is very all-consuming if you want to go all the way.

WR: Do people overstate the importance of rock and roll?

RD: It's a very individual thing. Everyone can buy a record, put it on, and they get to listen to it in their room. When you get through making an album, pressing it and playing it for record companies, doing publicity, in the end, it's a guy singing a song and a person sitting in a room listening to it. It's a very personal thing.

I don't think rock and roll has gone astray, or that it's any more than it is. A lot of people put importance on it. People [think that] without rock and roll, they'd be complete casualties. It makes people believe, believe there's a singer out there, or a band, going through the things that they are going through. I get a lot of that from fans who relate to all the stuff I write. I'm sure other bands do as well.

So I don't think you can emphasize its impact too strongly. It's made the most incredible impact on the world, more than any other energy, in the last 25 or 30 years.

WR: The Kinks’ personnel is mostly intact?

RD: No. Drummer Mick Avory left the band about 18 months ago. He plays on one track on the album, "Rock and Roll Cities," which Dave [brother Dave Davies] brought to me. He played me the demo, I thought it was really good. I said we should do it, but try to keep the drum in. He said, Mick did that. So we left it.

Bob Henrit [formerly of Argent] was just settling in after a year. It takes a long time to learn the repertoire, and learn the telepathy on stage. It's just a very difficult thing, it's like someone coming in to do a play without a script. And you have to pick it up as you go along.

WR: Lasting as long as the kinks have is some kind of accomplishment. What has kept the band alive and together over the years?

RD: I'm not sure. I don't know what the Rolling Stones would say, because they're the only other band that has been around longer than we have.

I think it's that unity. That sense of when you are together, it's the best way of playing that particular music. There's a camaraderie with the band that is very special. It's like a successful football team. It's great to play on it.

When you have the bad times, the famine times, you work harder to help each other out. It's a team effort, although I'm the person who does most of the writing. People focus on me because I'm the most creative member. But with Avory, he was a mainstay, a leveler. It's a blend of personalities. I'm not sure how long it will go on for, but I'm very happy doing it. I'm very happy with the record, and I can't think of anyone I'd rather play it with.

WR: You make is sound like one big happy family, but you and Dave Davies were known for…

RD: Being brothers?

WR: Yes. Are things better between you?

The Kinks. Ray Davies is on the left, Dave Davies is on the right. Courtesy of BMG.

RD: No, those sort of relationships get worse, actually. I think we try to be sensible, and adult about it. But…he was playing on a hit record when he was 15 at a time when rock and roll was some weird thing people did, it wasn't the kind of thing people did professionally. So, it's a tremendous adjustment we had to make, and people who knew us. It's a weird kind of job, and it makes emotions work in very strange ways. We're still basically brothers who don't get along, but we work together and we try to do what we do as well as we can. Obviously, if there's a flare up, or personality conflict, it's the worst possible thing, working with a relative. It's awful, but there we have it, and it's worked out quite well.

WR: For a long time, you were writing songs about middle class and blue collar people. What do you think about people like Bruce Springsteen and John Cougar Mellencamp finding it such a productive topic right now?

RD: Mellencamp? When he toured with us he was just John Cougar. What happened? He always used to work very hard. He even rehearsed right after sound check. They used to rehearse in the dressing room with all their instruments. Their success is due to that, they struggled quite hard.

WR: What do you think of these artists finding success in writing about the blue-collar worker?

RD: What's that?

WR: The "common working man. "

RD: Where I come from, working men don't have collars, they don't have shirts. It's all very noble, very nice, very marketable.

WR: Do I hear a trace of disdain there?

RD: No! It's very marketable. Hey! Let's stand up. Let's clench our fists, man! Speaking of "Born in the USA," it was a well put-together campaign. Credit that to the writer, he's been writing that kind of thing for a long time. Someone like John Cougar, in the shadow of someone so monumentally successful, it's always difficult. He's like a guy who wrote when William Shakespeare was writing. He [the other guy] also wrote some very good plays. [Back to Springsteen] He's come around at a time when the industry can market something like that. It's mega-mega successful, and people can relate to it.

Ray Davies (with bow tie) and the Kinks, early 1970s. Courtesy of BMG.

WR: In the last year rock discovered its social conscience with benefits for Live Aid and Farm Aid and Amnesty International. Do you see that as a positive in our culture, or is it marred by expediency and self-interest?

RD: It's a very good thing to raise money, do fund-raising. It's just that, all the self-congratulation people are doing, patting each other on the back, I think it's all a bit sick, personally. I do like the people who are not rock stars, who work very, very hard at Amnesty International, and for famine relief, who do not get known. And they'll keep doing the work when the other people have gone on and pursued their recording careers. I don't want them to be forgotten. But it's a great way of using this machine to raise a lot of money very quickly. That's alright: It's a good exercise.

WR: You have mixed feelings about "the machine" – is the rock and roll biz machine one you’re now comfortable working with?

RD: I don't feel comfortable in any system. You should function in a system, but always question it. Once people stop doing that, that's when you have dictatorships. That's why you should always have two parties. I would never accept any system, even if it favored me, or helped me. I'm not trying to be negative, with music or politics, but you've got to question the motives. Because it's very easy to get corrupted, and be corrupt.

WR: What did you think of Van Halen’s version of "You Really Got Me? "

RD: Yeah, I liked it. I enjoyed it more than I thought I would...It's just the fans, when we do it at gigs, come up and say, "we really like the Van Halen song you do."

This article originally appeared in Critical Conditions, the Substack blog of Wayne Robins, and appears here by permission.