Sometimes you encounter stories where it turns out that the story you think you want to tell, is just a very small part of a much bigger story.

This is one of those stories-within-stories.

Back about 1972 I encountered the brand Quintessence, at J.C. Gordon Company in St. Louis. J.C. Gordon was already a well-established company then, having started in the ’50s, I think. The owner was a gent named Robert Shaw (“No, not THAT Robert Shaw”, was his standard opening); if memory serves, he was a retired General from the Air Force Reserve. At any rate, he worked in live orchestral recording a lot, knew the audio biz well, and was an early dealer for Audio Research and Magnepan. His store was the first place where I heard an ARC/Tympani system—and I wasn’t really sure what to make of it.

Hearing “You’re So Vain” on a big boy multi-amped ARC/ Tympani system, I said, “I think it’s kind of a jukeboxey sound.” What I meant was that it was big and tubey and spacious, and I didn’t know how to describe it then. Shaw immediately said, “oh, I think it’s a GREAT sound”—and it was, really. It just wasn’t at all what I was used to.

As a 16-year-old longhair in wrinkled denim, I often encountered a lack of enthusiasm in audio stores, if not outright hostility. Not so with Bob Shaw: he was genial, if watchful. He listened to the questions I asked, and nodded approvingly enough times to indicate that I passed his “test”. The final question came when we approached a display of Quintessence gear: “Do you know what ‘quintessence’ means?” As I recall it, my answer was, “The ultimate, the epitome. the best.”

Again, he nodded approval—and we moved on to look at the gear. The preamp had a beautiful golden faceplate (as you’ll see in the pics on this page) and Mr. Shaw indicated that Quintessence was the best-sounding solid state gear they had. I don’t recall that I actually demoed the gear: stints w/ B&O gear and the Bozak Concert Grands preceded the move to another building with the ARC system.

Nonetheless, the brand of Quintessence made an impression upon me. When I recently decided to write about the brand for this column, making the leap of faith as usual that I would be able to find enough info to actually write a sensible outline of the company’s history, I found—nothing. —Okay, a few ads and one magazine review provided the info that the company was based in Sacramento. Beyond that—no names of prncipals, nothin’.

Turns out, there may have been a reason for that. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

When in doubt, I ask folks who have been around audio even longer than I have. They were able to provide a sketch, if not the full picture.

Walt Stinson’s dealership Listen Up has been a mainstay in Denver and the surrounding areas for many years. In fact, the company was started around the same time that I saw that Quintessence gear in St. Louis—1972. Walt was a Quintessence dealer and provided the pics of the gear on display, along with this snippet: “Of course [I remember the brand]. Very beautiful and unique. Purist approach, minimalist design, good sound. Not long in the marketplace. Very rare (I’ve never seen a used piece). I don’t recall meeting the principals. Took this photo [the close-up image] for an ad.”

The Quintessence preamp on display at Listen Up, back in the day---far left, under the Phase Linear amp.

The Quintessence preamp on display at Listen Up, back in the day---far left, under the Phase Linear amp.Sacramento-area designer Richard Marsh said, “ yes, the people there were also part of ESS and then Pass labs. Barry Thornton I believe was running the Quintessence brand at that time. And after ESS folded also, N.Pass opened his own business.”

That at least provided the name of Barry Thornton. ESS? Pass Labs? Maybe Nelson Pass knows something.

Nelson wrote, “ESS and Quintessence were in Sacramento and did some business, but I am not very certain of its history. I know that they did an active crossover for ESS, and there was some hanging out together. In 1971 or so ESS acquired the talents of Peter Werback, and they went into the business of amps and preamps. I knew Peter from UC Davis, and followedhim to ESS where I did R&D in speakers, arriving about a month before Oscar Heil.

“At Quintessence, Barry Thornton [there’s that name again!—Ed.] seems to have done the electronic design. He subsequently went to work for SAE (Morris Kessler) to do a “non-switching” amp in the late 70’s.

“He once showed me the preamp circuit which I recall was an LM709, which is perhaps the most ancient of the popular monolithic opamps, and he biased its Class B output stage with a resistor from output to negative rail.

“He also designed their power amplifier, and was kind enough to show its schematic, which was interesting – an LM709 (one of the earliest monolithic op amps) for the front end,ultimately driving a stack of Push-Pull Common-Emitter power devices, 2N6031’s and 2N5631’s as I recall, which had a sort of totem pole arrangement where the first pair were biased up at idle, and successive pairs came into play as output current increased. I am not certain how well it worked, but I thought it was quite original.

“Barry ultimately became an electronics rep in Arizona, and I haven’t heard from him since.”

The tech info is a little over my head, but Nelson’s comments again pointed to Barry Thornton as the guy.

The usual search of period issues of Audio, Stereo Review, and High Fidelity magazines, courtesy of the amazing American Radio History website, yielded very little. No mention of the mysterious Barry Thornton at all. Early ads presented a company that appeared to have sprung forth fully-developed, with a strong sense of maturity and self-assuredness. Here’s an Audio ad from 1973:

This brief feature in High Fidelity, also from 1973, provided more details:

This brief feature in High Fidelity, also from 1973, provided more details:

All those products sound like a fairly ambitious launch for a new company. I never found any indication that the control module or electronic crossover made it to production.

That same year, an Audio ad listed 20 dealers, a few of whom are still around (pardon the image quality):

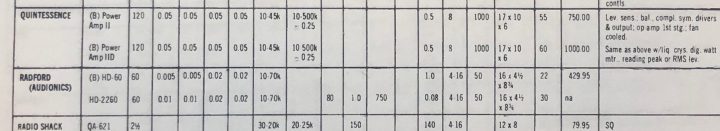

The 1973 Buyer's Guide of Audio provided full details of the Preamp, Equalizer, and Power Amplifier (in two variants). By the way---while the Quintessence preamp was $329.50, the Audio Research SP-3 was $595.00.

The 1973 Buyer's Guide of Audio provided full details of the Preamp, Equalizer, and Power Amplifier (in two variants). By the way---while the Quintessence preamp was $329.50, the Audio Research SP-3 was $595.00.

By the time those products were listed in the 1975 Buyer's Guide, the Preamplifier was priced at $500, at the same time that the Levinson JC-2 was $1050.00. 1975 ads in Audio described the Power Amplifier and Equalizer in unusual detail:

By the time those products were listed in the 1975 Buyer's Guide, the Preamplifier was priced at $500, at the same time that the Levinson JC-2 was $1050.00. 1975 ads in Audio described the Power Amplifier and Equalizer in unusual detail:

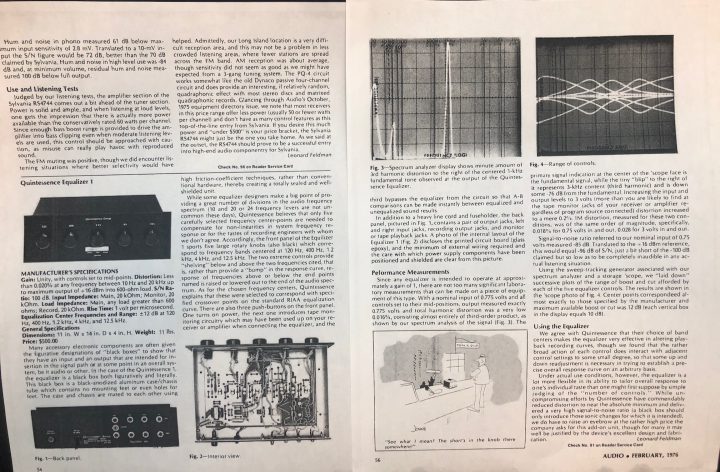

The single product review I unearthed ran in Audio in 1976. The venerable Len Feldman put he Equalizer 1 through its paces, and was impressed by its performance and build. The review concludes with Feldman sniffily saying of the $500 price—the EQ’s price jumped from $329.50, as did the price of the Preamplifier—“We do have to raise an eyebrow at the rather high price the company asks for this add-on unit, though for many it may well be justified by the device’s excellent design and fabrication.”

Not exactly damning with faint praise, but not exactly a rave, either. It’s the kind of thing that gives manufacturers and PR guys stomachaches—believe me on this.

This is all well and good, and gives some sense of what Quintessence did. But who was Barry Thornton, and what happened to Quintessence, a company that seemed to have such potential?

A little Googling led me to Austin Audio Works, a small company whose principal is a guy named Barry Thornton—and reading the notes on the company’s website made me pretty sure that this was indeed the same Barry Thornton. After the usual back-and-forth that seems to precede getting anyone on the phone these days, a lengthy conversion with Barry assured me that, yup, he’s the guy,

Quintessence, it turns out, is just a small part of the much bigger story of Barry Thornton. Based on our conversation, here’s how it went:

In the late ’60s, Barry attended Sacramento State. He and a group of cohorts/unindicted co-conspirators realized that if they formed a club or organization sanctioned by the school, said school would underwrite them with funding and other resources. And so, The Society for the Advancement of Electronic Music was born ( contemporary printed accounts and the poster below refer to the group as SFTAOPM—the Society For The Advancement Of Pop Music. Memories fade, and morph.) And what does one do with such an organization?

According to Barry, what they did was go to visit Bill Graham at the Fillmore in San Francisco, and convince him to book acts for four nights, instead of three. The Fillmore would get a better deal, and the Society would get the acts for a fourth show at the school in Sacramento. As if that weren’t ambitious enough, the Society’s first two concerts in 1968 were Jimi Hendrix and Buffalo Springfield.

The Sac State show: $2.75 in advance, $3.00 at the door.

At some point the school (>cough<) took issue with the considerable funds brought in by the concerts promoted by the Society. The group disbanded, and having built what he called a “hi-fi PA system” for the group’s shows, Barry hit the road and did live sound. “First I did Jethro Tull, then all the Chrysalis Records acts.”

Having started with tweaked Dynaco amps for power, Barry designed and built “amps that wouldn’t break”. Word got around, and other touring groups wanted the amps. So— an old schoolhouse was rented in Sacramento, and the amps were built using “hippy slave labor. They were basically hippies, but they showed up for work on time.”

At some point—dates are a tad shaky— Barry crossed paths with the local company ESS, especially Stan Marquiss, one of the company’s four founders. Barry was tasked to design an electronic crossover for ESS, then got the idea to design a sophisticated phono preamp. The decision was made to create a company to market the preamp and other products, and the schoolhouse and its crew of hippies became the Quintessence Group, and products were designed, built, and sold under that brand name.

When I asked why there such limited print coverage and advertising, Barry said, “that was by design. We put our efforts into visiting and training dealers, evangelizing and creating a tribe, rather than relying on the old ways. And it was very effective for us.”

In time the schoolhouse became too small for Quintessence, and 4,000 more square feet was added to accommodate 14 “ex-hippies”, a full chassis-building shop, an anodizing facility, board production, assembly—“we did everything in-house. And we were really proud of that.” The company grew to have 50 dealers, according to Barry, was profitable, and reached a few million/year in sales.

As well as producing Quintessence Group-branded products, there was still consulting work. Barry again: “[we were] active in the development of Quad. We worked with CBS labs to do subjective performance of FM-transmitted Quad using live sources and its changes through the distance of the receiver to the transmitter. We had a line of precision compressors, portable recording and broadcast mixing desks, line equalizers and monitor amplifier. Fun days.”

And then, as often happens, the shit hit the fan.

“I got a divorce. My dad was a judge, ” said Barry, ” and he advised me that unless I wanted to fight over my future earnings forever, I should just give my wife everything, and be done with it.

“So that’s what I did. She had no interest in the company, wouldn’t have known what to do with it. I sold the company and gave her all the money. And that was it.”

That wasn’t quite it for Quintessence. A local group of investors bought the company, and sold sub-shares to others…and may have oversold the shares, as in The Producers. The only press coverage I could find about the company post-sale was in a 1976 article in High Fidelity, a hard-hitting look at the then-current trend towards black faceplates (!). It read: “Quintessence (like SAE, devoted to high-performance separates) has re-emerged under new ownership with all its gold faceplates changed to black.”

Barry laughed when I read that to him. “Hell, we’d always done black, as well as the gold. We did all our own anodizing, so it was no big deal.” So much for accuracy in reporting.

One final appearance in print: Stereo Review’s 1978 Stereo Directory & Buying guide listed the the Equalizer and “Studio Preamplifier”, both now priced at $550. Two amps were listed: the 1-R, 90 watts/channel, at $650, and the II, 200 watts/channel, with “dual feedback loops and separate power supplies for each channel”, at $1300.

From all appearances, Quintessence the company vanished shortly after that. But Barry?

Barry Thornton was just getting started. Discussing the Austin Audio Works headphone amp on Head-Fi in 2014, Barry summarized his career:

“My first time in Austin was with Jethro Tull, I did the sound for them, had a big hi-fi sound reinforcement system I designed and built in college (Physics and Anthropology) using hippy slave labor. I then started the Quintessence Group AudioWorks, high end preamp, equalizers, amplifiers, went on to Chief Engineer at SAE (Hypersonic Class-A Series), Hasbro Electronic Toys, Monster Cables Techno-Evangelist, then Director of MC’s Professional Products, somewhere in between I did products for Parasound, Fostex, Audionics, Star, the interior electronics design for the PlayBoy Mansion, SF Ballet and Opera, a bunch of other big deals, and some more that will come to me. 5 Starts, 30 patents, I was VP OptoDigital Design, a Div of Monster, came to Austin through the Technology Incubator doing OptoDigial (professional digital and video over fiber for venues, Disney, Alamo Dome, Bulls Stadium, baa, blaa, we designed and built the hardware and software). My biggest gig was founding ClearCube (Blade computers, virtualization, what you now call the cloud) in my garage and going to 250 people, then retired. I was VP OptoDigiatal Design, a Div of Monster, came to Austin through the Technology Incubator doing Optical (professional digital and video over fiber for venues, Disney, Alamo Dome, Bulls Stadium, blaa, blaa, we designed and built the hardware and software).

“Boring – And by the way, what I did doesn’t mean crap, it’s where my dreams are going that count, the rest is the dead past, never to be done that way again. As is said, don’t look back.So I started Austin Medical Research, and in a couple of years was making pain go away with EMP and growing hair with lasers. That is now called ManeGain Inc. and is in public stock sales.”

Barry’s now working on developing still more ideas, and does Austin Audio Works more or less as a hobby, for fun.

Barry’s 75, still active and looking towards the future. I hope I can follow his example.

[Thanks to Walton Stinson of Listen Up for the header pic and the image of the Quintessence pre on display. As mentioned, Walt was a Quintessence dealer, back in the day. And of course, thanks to Nelson Pass, Richard Marsh, and Barry Thornton for their time and stories—Ed.]