Just as I was running out of things to write about for Copper, a mysterious gift landed on my doorstep. One day, someone left a large bag at the reception of my clinic. When I was able to get a minute after my morning session, I took a look and found about three dozen commercial four-track tapes. It turned out that the tapes were delivered by a friend who knows I am into reel-to-reel tapes. In fact, the tapes were given to him by a mutual friend, a conservatory-trained musician turned high-powered lawyer. Our mutual friend's father was a music lover and audiophile, and left his daughter a large collection of music, mostly LPs but also some reel-to-reel tapes. It was her father's passion that inspired her to train as a musician, but it was also due to her father's insistence that she ended up going to law school. Call it old fashioned Chinese paternalistic instinct. She has no means to play the tapes and gave them to my friend, knowing that he is an audiophile. My friend has no interest in getting into tapes and hence I received this manna from heaven.

My friend was only half correct that I am into reel-to-reel tapes. Both of my tape machines are professional studio models, designed to play two-track stereo tapes. In order to play four-track tapes, a consumer or prosumer machine is needed. The tapes I received are very attractive, mostly classical titles and box sets of operas. Most of them are highly-regarded recordings in both musical and audiophile terms. Having been convinced by Ken Kessler, through his articles in Copper, on the merits of four-track tapes, I bit the bullet and decided to invest in the equipment in order to play these tapes. In fact, I already had a handful of four-track tapes on my shelf, which I bought years ago. These are celebrated recordings that would have cost a fortune to buy on first-pressing LPs. One could buy the tapes in those days for about $5 each. I also briefly owned an Otari MX5050II prosumer machine equipped with both two-track and four-track playback heads, but gave it away due to a lack of space.

I would like to share my experience during this journey with readers of Copper, and I am convinced that even though the prices of the tapes have gone up in recent years, they still represent tremendous value as a source of audiophile recordings.

Just a quick primer on the history of commercial reel-to-reel tapes. These started appearing around 1954 with the advent of stereophonic recordings. Since the record labels had not yet found a way to reproduce stereo on LPs, the earliest stereo recordings were only available on tape. Initially, two mono playback heads were placed staggered side by side to play the two stereo tracks, which resulted in a small distance between the head gap of the heads. If these tapes are played with a stereo head, the two channels will be a few hundredths of a second out of sync. Soon, true stereo heads were invented, the so called in-line heads. The tapes were typically 1/4-inch wide, played at a speed of 7.5 inches per second (ips) and sold on 7-inch plastic reels. Each reel could hold a maximum of 48 minutes of program, roughly equal to one LP. The cost was very high compared to LPs, and only well-heeled and very serious audiophiles would buy them.

After a few years, the record labels introduced the four-track format. Each track is therefore half the width of the previous format, and the reel is flipped over and played back in the other direction after one side has ended. Halving the track width comes with a penalty of 2 dB of extra noise and slightly higher crosstalk (due to a smaller distance between the tracks), a small price to pay for a 50 percent savings on tape stock. The price of the reels became more affordable, but they were not big sellers even back then, especially after stereo LPs became available at a much lower price. Later, tapes that play at 3.75 ips were introduced to lower the cost further. These were mostly pop music and “best of” compilations of popular classical and easy listening hits. These tapes still sound better than cassettes, but the sound quality is too compromised to be taken seriously by audiophiles.

Four-track tapes continued to be sold until the mid-1980s. The quality improved over time, and some tapes produced in the late 1970s and 1980s were encoded with Dolby B (and rarely dbx) noise reduction. The tapes were copied on banks of specialized tape recorders in parallel, sometimes hundreds at a time, at high speed. All four tracks were copied at the same time, which means two tracks were copied backwards. Some people claim that it is better to copy tapes backwards, since the leading edge of transients becomes the trailing edge and is less demanding to reproduce. I have done quite extensive comparisons using professional tape recorders and copying at normal speed, but I could not hear any difference.

With the wide range of music formats available to audiophiles nowadays, including CDs, SACDs, streaming, high-resolution downloads, LPs (digital and analog), and even master tape copies, why bother getting into this ancient format at all? I think music lovers who appreciate the recordings made during the “golden era” of stereo recordings, roughly between 1954 and the mid-1970s, should take a look at this format. After all, many collectors still lust after the original LP pressings of recordings from Decca, EMI, Mercury, RCA, Everest etc., and will pay hundreds or even thousands of dollars for mint copies. Today, one can buy the tapes that were released at the same time as the original LPs for a fraction of the price of the latter. Bear in mind that when first released, the tapes cost at least three times as much as the LPs.

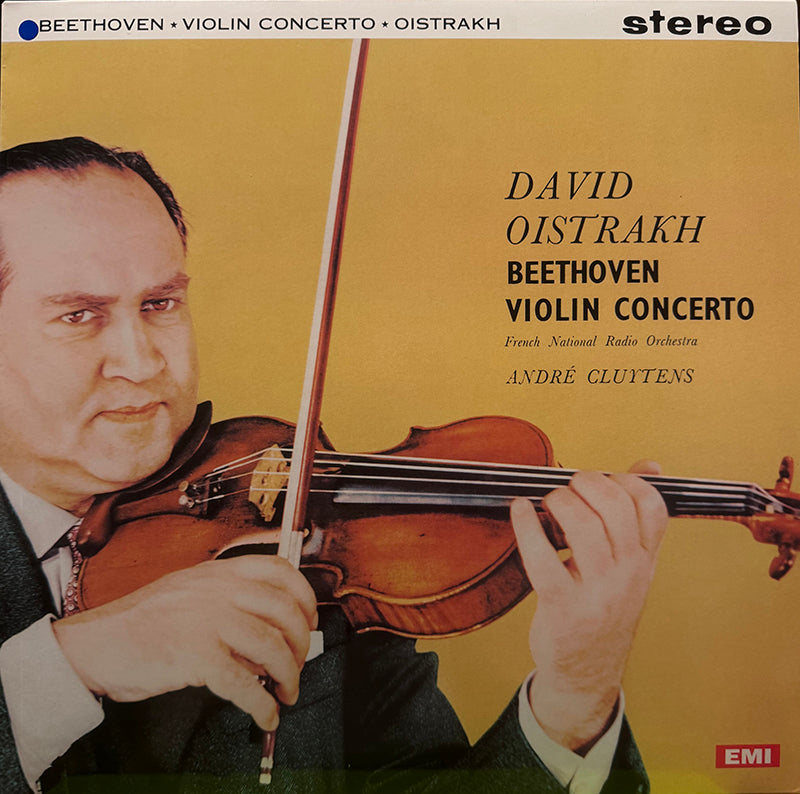

Let's take the famous recording of David Oistrakh playing the Beethoven violin concerto on EMI/Columbia (SAX2315), released in 1959, as an example. A near mint copy of the first pressing would cost more than £1,000 ($1,200). Even the later pressings cost at least $400. I managed to find a new old stock, still sealed copy of the tape for $100, while used copies in good condition would normally cost $50 or less. This price is already on the upper end of the range for classical tapes. Less-rare titles usually go for $10 to $30. Get them before others catch on.

Collectors of vintage records argue that the early pressings are superior to modern reissues because the master tapes would have been in better (spanking new) shape. After repeated use over the decades for reissuing LPs, CDs etc., many of these tapes have significantly deteriorated. Moreover, the original LPs were mastered under the supervision of the artists and producers, whereas the mastering engineers who cut the modern reissues often try to “improve” the sound to cater to the audiophile market, an issue I have discussed previously. Worse still, most modern LPs are cut from digital files, since labels are increasingly more reluctant to touch their irreplaceable master tapes.

The major disadvantage of vintage records is groove wear. Home audio equipment of that era was crude, and more prone to wearing down or outright damaging the record grooves. Early LPs in general lack consistency, and the state of the stampers when the LP was pressed makes a huge difference in sound quality. Contrary to folklore, the pressing information on the “dead wax” (the area between the end of the record groove and the label) is often unhelpful for choosing the best-sounding records. The only way to tell is by listening.

My impression so far is that four-track tapes tend to be more consistent in quality as long as they are well stored. This is not surprising as the whole production process involved less manipulations, and their target customers were more discerning than average. I have also noticed that there is less dynamic compression on tapes than on LPs in general, probably because some recordings were simply not reproducible by the record players of that era unless the dynamics had been reduced. This means the tapes often have a larger soundstage and sound that is more dynamic than the LPs.

This is not to say tapes are faultless. The biggest worry about old tapes is the “sticky shed syndrome.” The problem started after back coating was introduced in 1970 by Ampex, soon followed by other manufacturers. After 20 or more years of storage, the back coating compound can absorb enough moisture from the atmosphere to become sticky. When the tape is played, the back of the tape pulls off the oxide from the playing surface of the adjacent layer, and the sticky substance also gums up the tape guides, heads and rollers.

One of the editor's tapes from 1969 showing sticky shed syndrome (note the areas where the oxide has come off).

When the problem first emerged, Ampex recommended baking the affected tapes at around 130 degrees Fahrenheit for several hours. However, this temperature is outside the safe temperature range listed in the technical specifications published by Ampex themselves. I have seen other recommendations such as placing the tape on a bed of desiccant (silicon gel beads) inside an airtight container for a week, or storing under a hard vacuum for three days to “boil off” the moisture. These might or might not work, but should at least not damage the recording. Fortunately, none of the commercial four-track tapes I have come across has back coating.

Another problem is “curly tape," which is common with old acetate-backed tapes. All the tapes I own use Mylar backing, and I have not come across this issue, but some of the earliest two-track tapes might have acetate backing. A less-common problem is squeaking, which is caused by the degradation of the lubricant on the playing surface of the tape. These tapes need to be re-lubricated with silicone liquid before each play. Out of the 150 or so tapes I have listened to so far, only three needed lubrication. All three were made in the late 1970s, two of which were Dolby encoded. The color of the backing is also different from the older tapes, which leads me to believe that some manufacturers switched to a different (cheaper?) tape formulation around that time.

The most annoying aspect of analog tape for many people is tape hiss. The hiss is random noise (white noise) generated when the magnetic particles pass over the tape head. The characteristic of white noise is that the energy increases with the frequency (doubles every octave), a fact that comes in handy when designing noise reduction systems. The noise level is inversely related to the track width and tape speed. Therefore, the compact cassette (1/8-inch four-track at 1.875 ips) is much noisier than open-reel and requires noise reduction to be acceptable. 7.5 ips four-track tapes have an acceptable amount of tape hiss generally, as long as the full dynamic range has been utilized. However, if the material has been transferred at too low a level, the tape hiss can be quite distracting. LP noise is quite random (clicks and pops), whereas tape hiss is consistent, and can be “tuned out” by the listener. It can also be quite easily removed by noise reduction systems, which I will get to later.

There is an ongoing revival in open-reel tape, which started with the California company The Tape Project reissuing recordings in professional distribution format (1/4-inch, two-track at 15 ips) around 2005. The last commercially available open-reel tape machine (the Otari MX5050) ceased production in the late 1990s, and up until recently, audiophiles had to contend with buying second hand machines. A number of workshops have been buying up old machines for restoration and modifications to be sold as audiophile equipment.

New designs started to appear about five years ago, pioneered by Ballfinger, and I can count at least three brands of tape machines designed from the ground up (Metaxas & Sins and Analogue Audio Design being the other two) now available. However, none of these can play the four-track format, and their cost is too high for my purpose in any case. It therefore comes down to buying a second-hand machine. Aside from sound quality, the major considerations here are the availability of spare parts, reliability, and ease of repairs. The most popular machines for restorers include the Revox B77, the Technics RS-1500/1700, and various Tascam models. Buyers can find many choices on eBay, but the risk is that some of these might require a lot of work or even be unrepairable. Even though I enjoy repairing things, open-reel recorders are not simple and require special equipment and experience to properly align and regulate. I therefore decided to buy from a reputable workshop.

I ended up buying a Revox B77 for several reasons. Revox was the largest manufacturer of tape recorders in Europe for decades, and their professional machines, under the Studer brand, were standard equipment in many major studios. The B77 was their most successful prosumer model, intended for serious audiophiles, radio stations and small studios. Technologies that tricked down from their state-of-the-art professional machines were adopted, including the tape heads. They were basically professional recorders scaled down to fit into the home audio market, both price- and size-wise. The PR-99, their smallest professional machine, is a B77 with balanced audio electronics. Spare parts are still plentiful, and new heads are still manufactured. Upgraded reproduction and recording electronics based on modern electronic components are also available. Since these machines were sold in large quantities, supply is plentiful in the used market at very reasonable prices.

The author's Revox B77 tape machine.

The Revox B77 models are available with a number of options. The standard machine runs at 3.75 and 7.5 ips and the high-speed version, which was aimed at the professional market, runs at 7.5 and 15 ips. There are also low -speed and super-low-speed versions that run at one half and one quarter of the standard speed, respectively, mainly used as voice recorders. Some of these low-speed machines were run 24/7 and are pretty worn out. The head blocks have separate erase, recorder and reproducer heads in their1/4-inch two-track or four-track versions. Most standard-speed machines on the market have four-track heads, whereas the high-speed versions have two-track heads. The B77 Mark 2 version has vari-speed control, but is otherwise identical to the Mark 1. Towards the end of the product cycle, Dolby B encoding/decoding was also available as an option.

The largest reel size that the B77 can handle is 10.5 inches. It has three independent direct drive motors, and the capstan is servo-controlled. Although it does not have tape tension control, it has servo-controlled electronic braking and tape handling is therefore very gentle. What it lacks when compared to Studer professional machines are the editing functions, although it has a built-in tape cutter. In stock form, the sound quality is already very good, probably better than any other consumer machines available at the time.

I decided to buy a machine from Nagravox, a tape machine specialist based in Australia. As the name suggests, they mainly deal with Revox/Studer and Nagra machines, and also sell new parts for repair and restoration. I chose to buy a high-speed machine and also bought an extra four-track head block. There are two reasons for choosing the high speed; the capstan motor runs at the same speed in all versions, with a different capstan diameter according to the version. The high-speed version therefore has the widest capstan, which gives better speed stability due to the larger contact area.

Moreover, I can just switch head blocks if I ever decide to play two-track master tapes with the machine. After all, the B77 is much more portable than my Nagra T. My machine is a Mark 1, since I don't need variable speed. Mark 2 machines are newer, but as all the parts that wear out were replaced anyway, it doesn't really matter.

The key to restoring a B77 is to replace all the original electrolytic capacitors, since these will invariably fail in short order if they haven’t already. The motors were stripped and worn parts were replaced, as were the bearings. The heads were re-lapped and professionally aligned. The original audio electronics have fixed IEC1/CCIR or NAB equalizations; playing tapes with different EQ will therefore require swapping the circuit cards for these EQs. Upgraded audio electronics are available from Audvance and these cards are built with the latest components, have selectable EQ, and result in a 3 dB improvement in signal-to-noise ratio. In my experience, it is a major upgrade in sound quality and the next best thing to using outboard tape head electronics, which would be much more expensive and requires extra space.

The final cost for the machine came to around $2,800. One can spend a lot more, since new faceplates and casings in fancy materials, designs and colors are available from various vendors. There is even an available digital tape counter and remote-control board that replaces the mechanical counter and allows the user to control the functions of the machine with a smartphone, including a shuttle function that cues to precise locations on the tape, and a database that remembers the position of each track. The user can therefore jump to different songs with (almost) the ease of a CD player!

Having bought about 120 tapes since receiving the original batch from my friend, I can conclude that it is a most worthwhile exercise. For many beloved recordings, the tape turns out to be the most satisfying format, at a cost that is often less than what one would pay for a new reissued LP. Some of these tapes quite frankly leave their LP cousins in the dust.

In future installments of the series, I will discuss noise reduction, and review the best tapes in my collection, comparing them to LPs (original and reissue) and master tapes when available.

Another David Oistrakh four-track tape from the author's collection.

Header image: David Oistrakh, Beethoven Violin Concerto, four-track tape.