This month the Melophile suggests music by composers who either deserve better recognition or are already well-known but have written major works that were overshadowed by their own “biggest hits.” The pieces included here were created during the 20th century but didn’t follow the avant-garde styles of the time: they are accessible and memorable…and there isn’t a twelve-tone row among them.

Blitzstein/The Cradle Will Rock/Gershon Kingsley, musical director (MGM original LP or CRI reissue LP) Marc Blitzstein, a talented composer whose theater/opera works were considered controversial because of their political and social content, gained national attention when his first musical opened off-Broadway in the 1930s. [1] The Cradle Will Rock, set during the Great Depression, is the story of a capitalist’s resistance to unionization in a fictional town controlled by the tyrannical Mr. Mister. Appropriately named characters include Mr. and Mrs. Mister, Reverend Salvation, Editor Daily, Moll (a prostitute), and Larry Foreman (the union leader) – roles that have been sung by performers including Jerry Orbach, Alfred Drake, Tammy Grimes, Patti LuPone, and Vivian Vance (yes, that Vivian Vance, aka I Love Lucy’s Ethel Mertz).

The Cradle was scheduled to premiere at the Maxine Elliott Theater in New York on June 16, 1937. In his The New York Times review of a 2019 revival, Jesse Green recounted the events of that day: “whether because of budget cuts or censorship, the production was canceled by its sponsor, the Federal Theater Project, on the day of its planned premiere. With the intended theater (and sets and costumes) locked down, the director, Orson Welles, then 22, decided to rent a space [the Venice Theater] 19 blocks north. The audience paraded to the new site but, in an irony more pungent than any of Blitzstein’s, the actors’ and musicians’ unions forbade their members to perform under the terms of their existing contracts. So Welles invited the actors to buy tickets and sing their roles, in street clothes, from their seats. On the otherwise empty stage, Blitzstein accompanied them at an upright piano, forgoing his 23-player orchestration.” [2] Green was critical of the lyrics but praised the music: “what…can sometimes make it beautiful, is the score, in which pastiche passages that mock the bad guys alternate with jagged, yearning arias that ennoble the others. (If it sounds like Leonard Bernstein, [3] that’s because Bernstein was a Blitzstein protégé.)” [4]

Most musicals have at least one hit song and “Nickel Under the Foot,” sung by Moll, is this musical’s most popular number. The picture quality of my favorite YouTube performance is poor but the sound is clear and Patti LuPone’s performance makes it “must see TV.” [5] For selections from the excellent LP recording referred to above, listen to scenes six and seven, where you’ll find dialogue and lyrics that provide parts of the plot, references to Mr. Mister and the Mrs., and several numbers including the title song and a different performance of “Nickel.”

The Cradle might be considered out of date or regarded as still relevant. However you feel about the subject matter the (now) overlooked music is nevertheless enjoyable. For more Blitzstein, listen to the rain in “The Rain Quartet” video from Act III of his opera Regina. [6]

Houseman tells “the true story” of The Cradle’s opening night (video from the 1986 PBS broadcast):

LuPone sings “Nickel Under the Foot” (video from the 1986 PBS broadcast):

The Cradle scenes 6-7 (LP):

“The Rain Quartet” from Regina (video):

Bernstein/Peter Pan/Alexander Frey, cond. (KOCH CD) West Side Story. Candide. On the Town. Peter Pan. Wait…Peter Pan? With songs composed by Leonard Bernstein?

Peter Pan brings back memories of Mary Martin, attached to a cable, flying around the stage in the 1960 black and white TV classic. Songs like “I’ve Gotta Crow,” “I Won’t Grow Up,” “Never, Never Land,” and “I’m Flying” come to mind…not a Peter Pan with music by the composer of “Cool” or “Gee, Officer Krupke.”

Bernstein’s Peter Pan opened on Broadway in 1950. Although it was both a critical and financial success the show was quickly obscured by the Disney animated version (1953), the Broadway production with Mary Martin (1954), the TV broadcast, and mostly by the quality of Bernstein’s other musicals: On the Town (1944), Wonderful Town (1953), and of course West Side Story (1957).

In his liner notes for the CD Daniel Felsenfeld writes: “Sometimes a classic slips away, needing revival, unjustly forsaken….The score is delightfully tuneful…[e.g.] ‘Dream with Me’ shows the composer at his Broadway best, with smooth, fluent harmonies, and a gorgeous, arching melody…’Spring Will Come Again’ [has a] plangent middle section [Bernstein later included] in a moving boy soprano aria in his Chichester Psalms…and ‘Build My House’ is a sweet tune, an innocent hortatory number Wendy sings to the Lost Boys as she lands in Neverland…” [7]

Although Bernstein’s most famous musicals get all the attention, the forgotten Peter Pan is worth revisiting. “The Broadway rendering of Peter Pan…has, until now, vanished into the unmerciful and often cruel mists of time….[This recording] stands as a loving exercise, a carefully prepared re-rendering of a hidden gem authored by a true master.” [8]

“Dream With Me”

“Spring Will Come Again”

“Build My House”

Barber/Violin Concerto/Gil Shaham, violin, London Symphony Orchestra cond. by Andre Previn (Deutsche Grammophon CD) Sometimes referred to as “the saddest music ever written,” [9] Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings was originally the second movement of his String Quartet, Op. 11. Like Eric Satie’s famous “Gymnopédie No.3” (consult the Melophile in Issue 138) you’ve almost certainly heard it on TV, in the movies, or on a classical music radio station in one form or another: the original string quartet, the arrangement for string orchestra, or version for voices.

The Adagio, like most of Barber’s music, is superb but has eclipsed his stunning Violin Concerto. No doubt about it: This is Romantic 20th century music with exquisite first and second movements and a breathless “perpetual motion” third movement where the violinist gets to strut his stuff. Sometimes violinists perform the melodic first movement too quickly. Sometimes they play every note so lovingly that the music loses its flow. In this recording Gil Shaham and Andre Previn emphasize the music’s lyrical nature without gushing uncontrollably.

Barber was criticized for being too conservative. After all, just about everyone else was experimenting with atonal music – intellectually engaging but emotionally unfulfilling. Happily, Barber and many other composers, including the ones discussed here, continued to write in styles that kept the emotional element alive while integrating 20th century techniques. You can listen on YouTube to the first movement alone or the entire concerto performed by Barber/Previn, or watch Shaham in action with a different conductor and orchestra by making your way over to the BBC Proms. Seeing the violinist play the challenging last movement is a special treat. (Note: Click on SHOW MORE to reach the second and third movements on both the CD and BBC video.)

Violin Concerto, first movement/André Previn conducting the London Symphony Orchestra (CD):

Violin Concerto/David Robertson conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBC Proms video):

Estévez/La Cantata Criolla: Florentino, el que cantó con el Diablo/Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela, Eduardo Mata, cond. (DORIAN Discovery CD) For many listeners the only South American classical music composer’s name that comes to mind is Heitor Villa-Lobos, the Brazilian who wrote Bachianas Brasileiras. But there are many other talented artists, like Venezuelan composer Antonio Estévez, who have been neglected and deserve recognition outside of South America.

The Venezuelan Llanos (plains) have inspired many artistic achievements. One of those is “Florentino y el Diablo,” a Venezuelan poem by Alberto Arvelo Torrealba based on a folk legend that recounts a singing contest between a llanero [10] and the Devil. La Cantata, set to that poem, is one of the most important works of choral-symphonic music in Latin America and it’s a knockout: exotic, percussive, rhythmic, and exciting. It incorporates one vocal “duel,” two Gregorian chants, and occasionally sounds like Stravinsky in a good mood. The third and final movement features the best part of a contest between the Devil and a llanero named Florentino. If you get hooked and want to hear more, go back and listen to the first two movements: They’re wonderfully atmospheric and dramatic, and include most of the choral music.

Bonus track: Watch the third movement of a live performance [11] with Idwer Alvarez singing the part of Florentino – the same role he sings on the Dorian recording. While the melodies are more apparent under Mata’s baton, this video (yet another with a variety of technical glitches) is an electrifying, almost manic presentation conducted by a very young looking Gustavo Dudamel practically flying off the podium. The soloists sing their parts at a rapid pace without biting their tongues…an impressive achievement. Don’t try this at home.

Mata: Third movement (CD):

First movement:

Second movement:

Dudamel: Third movement (video):

[1] Blitzstein also gained attention in the 1950s for his English translation/adaptation of Brecht and Weill’s Threepenny Opera.

[2] For additional information about the opening performance, listen to John Houseman’s first-hand account on the 1986 PBS airing of a 1985 Acting Company production of The Cradle.

[3] “We are almost telepathically close. Sometimes we compose startlingly similar music on the same day, without seeing each other.” Marc Blitzstein on Leonard Bernstein, in “Remembering Blitzstein in the Bernstein Year” (marc-blitzstein.org, January 17, 2018).

[4] “Blitzstein’s influence on Bernstein’s intellectual and musical development was said to be considerable. As Bernstein became increasingly recognized and venerated in the music world, he continued to commend in Blitzstein a musical purity that Bernstein himself had sacrificed in his rise to fame…When they had met, Blitzstein was riding high, but his protégé would quickly surpass him in popular renown, critical admiration, and financial success.” Christopher Caggiano, “Bernstein on Blitzstein, Blitzstein on Bernstein” (everythingmusicals.com, 4/14/2018).

[5] Video excerpted from the 1986 PBS airing.

[6] Based on Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes.

[7] The songs and almost all of the lyrics were written by Bernstein but because of other commitments he didn’t have time to compose the show in its entirety. As a result he commissioned his life-long friend Marc Blitzstein to help out with a few of the lyrics.

[8] Daniel Felsenfeld. Some music was cut from the original production and this CD is the first recording that contains the complete restored score.

[9] Thomas Larson, The Saddest Music Ever Written: The Story of Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” (New York: Pegasus Books, 2010). If you want to challenge this conclusion get out your handkerchief and try listening to Górecki’s Symphony No. 3.

[10] The strength of the Venezuelan countryside is said to be contained in the power of words and singing. The “llanero,” or plainsman, uses words to chase away death, tame animals, challenge his enemies and engage in duels, fully assured of his victory.

[11] No performance information given.

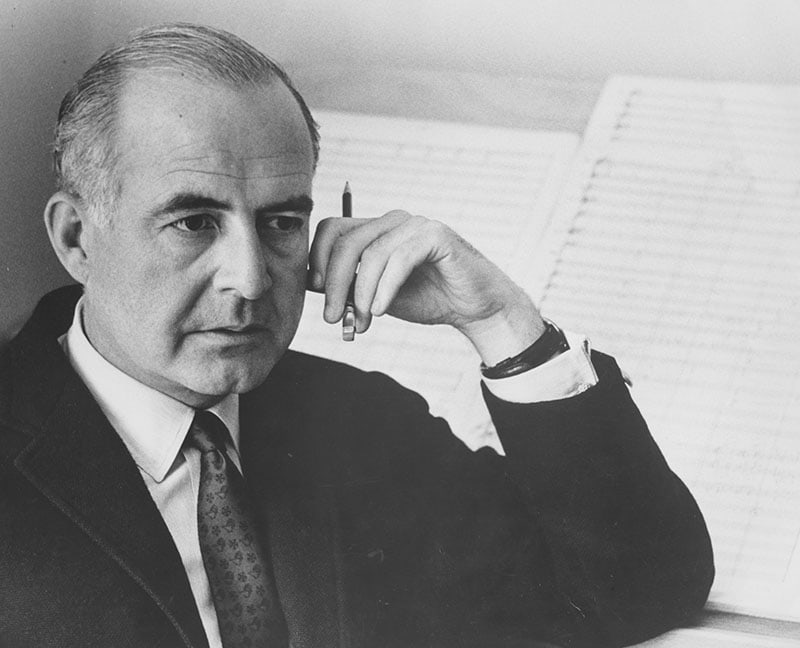

Header image: Samuel Barber.