Recently, Copper contributor Larry Jaffee, the co-founder of record industry conference Making Vinyl, gave a talk at Long Island University called “The Ambivalent Jewish Lives of Two Rock Gods.” Jaffee is currently an adjunct assistant professor teaching Writing About Music at St. John’s University. For the lecture, Jaffee researched Lou Reed and Joey Ramone’s experiences as Jewish young men growing up on Long Island, and how it influenced their music and lives. I had planned on attending the session but unforeseen circumstances intervened. Larry and I are also Jewish.

So, I asked Larry to send me the slides for his presentation as a springboard, and used them as the basis for this interview. (You can view the video of Larry's presentation at this link.)

Frank Doris: As you point out, for a lot of Jewish people, including Lou Reed and Joey Ramone, Judaism influences their lives, but they don't wear it on their sleeve. For both Reed and Ramone, they went out of their way to avoid talking about their Jewishness early in their careers, but thought differently about it by the end of their lives.

Larry Jaffee: The interesting thing is that his first wife Bettye Kronstad told me that when they would visit Lou’s parents, he was the perfect Jewish husband. Not so much from a religious standpoint, [but] just protective of his wife. He felt like he should be the breadwinner. They weren't even married in the early years. They met in 1968 and he wanted to marry her right from the start, and she kept fending him off. And then finally, guess it was 1972 or 1973, she finally just said yes and [felt like] he was head over heels for her. Although she was concerned about his drinking problem.

FD: Lou Reed has this image of being a rock and roll badass, and picturing him having a Bar Mitzvah and going to temple doesn’t square with the image he was cultivating.

LJ: But you and me and both of them, we were controlled by our parents. We didn't really have a lot of say in the matter.

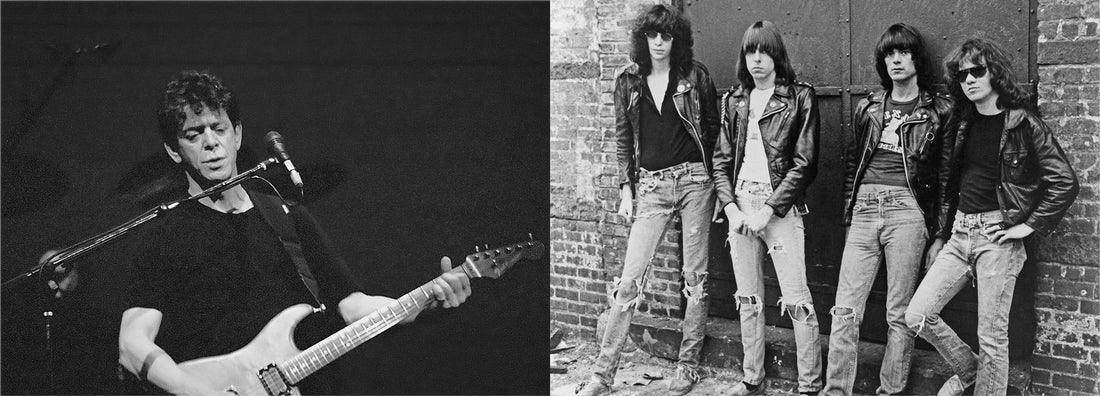

Lou Reed at the Hop Farm Music Festival, July 2011. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Man Alive!

FD: Being a rock star is so intertwined with your public image, and it was especially so in the pre-internet days. It was all about cultivating a mystique, a persona, and if people like Joey Ramone or Lou Reed or any rock star, for that matter, told the world they were Jewish or Catholic or atheist it would break the air of mystery.

For you and I, growing up Jewish in the towns where we were on Long Island gave us a feeling that we were in a minority. As you’ve noted to me, you encountered anti-Semitism in your high school. And feeling like being in a minority had to have informed Lou Reed’s and Joey Ramone’s lives. Lou Reed’s family changed their name from Rabinowitz. Joey Ramone’s real name was Jeffrey Hyman. So you’re looked down upon by a portion of society because you were a rock and roll musician, and in some circles, also because you were Jewish.

LJ: Joey's case was a little different because his parents went through a divorce. Lou's parents did not. Lou obviously had [great] musical talent.

The Ramones in 1977, with Joey Ramone at left. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/press kit photo.

FD: You said that in November 1975, Lou Reed heard a tape of Ramones demos from Danny Fields (soon-to-be co-manager of the Ramones) and responded, “middle-class Jews are going to be so offended by this.” Why would he think that?

LJ: Joey was a hippie. That was one of Johnny Ramone's complaints about him. Whereas Lou was older and was more probably under the influence of Mad magazine and Lenny Bruce, and loved doo-wop music. And [Lou’s] parents were concerned [about him]. They gave him electroshock treatment. I think that had a lot to do with the way his personality was, why he was so angry a lot at the time.

Getting back to his thoughts about the Ramones demo, [he really liked it] and said something like, “this is what parents were afraid of.” What astounded me is that I had never heard Lou Reed get excited about anybody [other rock bands]. When I finally had a direct encounter with him we talked a little bit about jazz, so I knew he could get excited about jazz, but never rock. It seemed like he disliked everything [in rock], including Patti Smith.

FD: You said that Lou warmed up to Judaism later in his life. I'm wondering if he just got more spiritual in general. I know he was into tai chi.

LJ: His second wife Sylvia gave me a couple examples of when things started changing. There was a 1981 Ralph Bakshi film called American Pop. It’s a story about four generations of Russian Jews who are musicians. One of the characters was obviously based on Lou as a blonde at his strangest period. Sylvia said that watching that movie hit him so hard, all of a sudden he [had a realization about his Jewishness]. They ate regularly at Jewish restaurants, and Sammy's Romanian Steakhouse on the Lower East Side was his favorite. They would go to Zabar’s and Barney Greengrass on the Upper West Side.

FD: I noticed in one of the slides in your presentation that Joey Ramone is buried in the Jewish section of Hillside Cemetery in New Jersey, and his headstone has a Jewish star on one end and eighth notes on the other. Was that specified in his will?

LJ: Don't know. I did send an e-mail to his brother, who's the only person that could really talk about that. But Mickey did not respond.

A book called The Heebie-Jeebies at CBGB’s: A Secret History of Jewish Punk devotes a lot of space to Joey and Lou, as well as other musicians from the evolving NYC punk scene like Richard Hell, “Handsome Dick” Manitoba [of the Dictators] and Lenny Kaye [of the Patti Smith Group].

Joey Ramone's gravesite. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Tony.

FD: I think I told you that when I first met Joey Ramone, backstage at a New Year’s Eve gig where our band was warming up for them (in 1980 at Malibu nightclub in Lido Beach, New York), I was surprised about how humble he was. When you see him up on stage, you think, man, this guy is a serious badass dude. And he was just this sweet guy. He was so nice to me and we talked quite a bit, and he gave me a lot of advice about what I might encounter if I wanted to pursue a rock and roll career. That was one of my first life lessons when I was young: that the person in the image can be very different from the actual person.

LJ: When I met him the first time in 1977 at My Father’s Place (a famous club on Long Island), they were going to open for Blue Öyster Cult at the Nassau Coliseum [at a later gig]. And I said to him, “it's a pretty big stage compared to My Father’s Place. What will you do with all that space?” He said, “I don't know!”

I find Lou and [his relationship with] Long Island very interesting because when he was a kid, he loved living in Brooklyn. When he was about nine or 10 they moved to Freeport (Long Island), and he found it traumatic. He had a really hard time acclimating. I wonder if it was from his parents [being concerned about him being Jewish in an unfamiliar environment] and warning him to be on your guard.

FD: When Lou Reed went to Syracuse (University), you said college changed everything for him.

LJ: He was at NYU for a semester or so, then dropped out. Apparently he had some sort of breakdown. He originally planned to go to Syracuse with a Jewish high school friend, and the last minute changed [his mind]. I think the reason he wanted to go to NYU is so he could go to jazz clubs. But meanwhile, he was going through electroshock [treatment], which began while he was in high school.

FD: He had to have been resentful about that.

LJ: At Syracuse, he was a bit of a troublemaker, and he also studied literature with acclaimed [writer and poet] Delmore Schwartz, his professor. He would go and get drunk with Schwartz, who was an alcoholic. Schwartz died in 1966, just before the first Velvet Underground album was released. Lou wrote at least two songs about Schwartz, “European Son” and “My House.”

Aidan Levy’s 2016 biography of Lou Reed, Dirty Blvd., contains amazing stories from his college friends, some who were his bandmates while they were at Syracuse. They would be booked for a gig at the Jewish frat house. Lou would show up purposely late, almost as if he tried to sabotage the gig.

Anne Frank statue, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, courtesy of Larry Jaffee. Steve Katz, Lou Reed’s former producer, tells a disturbing story in his 2015 memoir about he and Lou visiting the Anne Frank House in 1973. After Lou came down from the stairs, he yelled for everyone to hear, “who the f*ck is Anne Frank?”

FD: It's impossible to sum up somebody as complex as Lou Reed in a few sentences, but what do you think Lou Reed's real impact will be when history looks back?

LJ: I think Lou’s lasting effect was him introducing – through the Velvet Underground – musical dissonance and [lyrical] subject matter that were not silly love songs. “Sister Ray” is a pretty amazing piece of music, but also lyrically, note the seedy story Lou is telling. Loaded was full of would-be hits if we were in a perfect world.

FD: When I first heard [“Sister Ray”] I literally didn't know what he was talking about. “I couldn't hit it sideways.” Later I realized, good lord, the guy's talking about shooting heroin. And then I realized after learning more about him that he wasn’t just making up a story. He was speaking from experience. This was probably unheard of before the Velvet Underground.

LJ: In the song “Heroin,” when Lou says, “when I'm rushing on my run and I feel just like Jesus’s son”…I wonder if this is a rebellion against his [Jewish] father? It’s similar to Dylan on “Highway 61 Revisited”: “G-d said to Abraham, kill me a son.” [I think] basically that was Dylan rebelling against his own father, whose name was Abraham. And then two [Velvet Underground] albums later, Lou has a song called “Jesus,” where he says, “Jesus, help me find my proper place, help me in my weakness.” I wondered if that was more rebellion against his roots.

FD: There's a part in your presentation where you say his wife Sylvia never saw Lou Reed angrier than when he felt that anti-Semitism was happening.

LJ: I think that was more in business encounters, like negotiating for a gig or a recording contract or something like that. He had friendships with Clive Davis (founder of Arista Records, one of Lou’s later record labels) and (Sire Records founder) Seymour Stein and I think he admired both of them because they were Jewish. And in both of their autobiographies, they talk about their friendships with Lou. In Clive's book (The Soundtrack of My Life), he said Lou would come to his apartment to watch the Thanksgiving parade down Central Park West and nosh on bagels. [And here’s Lou with] his black nail polish.

FD: What an image.

In their own way the Ramones were just as groundbreaking as Lou Reed, and certainly not appreciated for it at the time. Did Joey have any sense that what they were doing was revolutionizing music and sowing the seeds for punk, or not?

LJ: When I finally sat down for a real interview with Joey and with Dee Dee separately in 1985, they were still angry at the band’s lack of success. They had been together for more than 10 years [at the time], were never taken seriously as a groundbreaking band in the US, [and] felt they were better-appreciated in Europe. They basically taught the Clash and the Sex Pistols how to do punk.

FD: Along with the Stooges and the MC5 probably.

LJ: Right.

Dee Dee Ramone and Joey Ramone, East Village, New York City, July 1985. Photo courtesy of Larry Jaffee, all rights reserved.

Danny Fields told Lou Reed that Clive Davis passed on [signing] the Ramones because he thought they were too raw. And Lou said, “oh, that's just like Clive. He doesn't even realize this is the future. How can he pass on them?”

FD: But I’ve heard time and again that Lou Reed became more at peace after he met Laurie Anderson, and he accepted death readily and was calm about it.

LJ: I asked him about whether he ever recorded with Laurie, and he felt he wasn't really worthy of that. Can you imagine? He called her “Madam Tech.” We didn't really talk about spirituality [when I met him]. He talked about racism, and he got really choked up.

The other thing about when I finally got to interview Lou – and it took me 25 years – was that I asked Lenny Kaye [author and guitarist for the Patti Smith Group] and [writer] David Fricke about what was the best way to deal with Lou in an interview. Lenny said, “stick with [talking about] technology.” So the magazine that I edited [at the time] was called Medialine, which covered [physical media and things like that]. I brought all our sister publications with me, Guitar Player, Keyboard, Modern Drummer, and Lou was devouring them.

Lou Reed at Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, Portland, Oregon, 2004, the year after Larry Jaffee's interview with him. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/dannynorton.

FD: He was fanatical about gear. And people think the guy can't play, but they say the same thing about Jack White. My response is, you try to play like that.

That's another thing about the Ramones. They were looked down upon for just playing two or three chord songs – which is actually not true – and people would say, “all he's doing is playing bar chords” about Johnny Ramone’s playing. And again, if you try to play like that, with all downstrokes at warp speed, you’ll probably give up after about a minute. I saw Green Day do a Ramones tribute and they needed two guitarists to get the sound of Johnny Ramone. And Joey Ramone could double-track his vocals perfectly.

Joey Ramone and the Ramones, Seattle, Washington, 1983. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Mrhyak.

LJ: Joey was originally going to be the drummer but he had difficulty singing and playing drums at the same time.

FD: It’s known that towards the end of the Ramones’ career they didn't like each other very much, and when they broke up it was with little fanfare. Even though the Ramones had success, it gets frustrating when you don’t get the recognition you deserve and it starts to wear on you. I don’t know how much of their breakup resulted from that, and how much was from personality clashes.

LJ: It goes earlier than that. Around 1980, Johnny was having an affair with Joey's girlfriend and then married her. It’s captured in Joey’s song, “The KKK Took My Baby Away.”

FD: When I tell people about some of the things we experienced as musicians being around New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s, they sometimes get jealous. It was almost like living in a golden age. Did you ever read the book Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever?

LJ: I have it here.

FD: It’s a brilliant analysis of what was happening at the time in punk, new wave, hip-hop, disco – really incredible. (The book is by Will Hermes, who also wrote the recent and excellent Lou Reed: The King of New York.)

So certainly, Lou Reed and Joey Ramone would have had a different musical and personal development if they hadn’t been Jewish and if they hadn’t grown up in New York. Do you have any final thoughts on that?

LJ: What I find interesting about both is that they acted out occasionally against their Jewish roots midway through their careers. For example, Lou actually had an Iron Cross briefly dyed into his hair in 1973. The turning point was in 1989 when on the New York album, he criticized a well-known politician for not renouncing a high-profile anti-Semite. Soon after Lou regularly attended the Downtown Seder organized by Michael Dorf.

A week after my in-person interview with Joey, he actually threatened me over the phone, inquiring whether the article I was writing, which was eventually published by Mother Jones, would include his real name and that he was Jewish. Both were germane to the article, which was principally about the Ramones song “Bonzo Goes to Bitburg.” Rumor has it that Sire did not release the song, which eventually showed up on a 12-inch import single from the UK indie label Beggars Banquet, because it didn’t want to risk angering the Reagan administration.

I told Joey the honest truth, that I did not know because I had no control over what an editor might do. His words, “I know where you live,” will forever echo in my brain. Meanwhile, he was buried in a Jewish cemetery.

Lou Reed’s autographs of the author’s original promo LP of Metal Machine Music (1975), and 8-track tape of The Velvet Underground Live at Max’s Kansas City.

Header image collage courtesy of Susan Schwartz-Christian from images sourced from Wikipedia.