That Old-Time, New Style Roll and Rock

You're sitting on a porch in the Shenandoah Valley, or maybe the hills of West Virginia, where freight trains are as common as a house finch or tufted titmouse. You hardly notice them. You're passing the pipe around with your new friends David Rawlings and Gillian Welch. They're friends because of the way their music always draws you in, makes you feel part of the conversation.

One of them says, "Saw a freight train yesterday," and at first you wonder what the deal is, because you see freight trains every day around here. Story continues: "Just a boxcar of blue/Showing daylight clear and through/Just an empty trainload of sky."

You try to visualize this, and it doesn't make any sense: a transparent freight car, with no sides or roof? The other says, kind of like a put-on: "Was it spirit, was it solid? Did I ditch that class in college?" In reply, the first one just quotes from a favorite Neil Young song.

"I said, Hey hey, my my." If the Welch/Rawlings body of work had four boxcars rolling slowly because the tempos are always slow but steady, moving forward without much if any percussion propulsion, one would be the Stanley Brothers, one would be Bill Monroe (spiritual forebears), one would be Bob Dylan, and one would be Neil Young (hovering gurus). And the sun shining down would be Elvis Presley, and all the music he mixed and mashed until it spontaneously combusted in Memphis in 1954.

No haste, no waste: Welch and Rawlings’ steady pace.

My favorite Neil Young cover might be Welch's live version of "Pocahontas," a bit of stoner time travel involving the massacre of Native Americans, the Astrodome, "Pocahontas, Marlon Brando and me." It's on a short album called Music from The Revelator Collection (2006), which features live songs from or left off Welch's game-changing Time (The Revelator) album from 2001, produced by Rawlings. It includes the nervy "I Want to Sing That Rock 'n' Roll," nervy because it was recorded live at the country music temple, the Ryman Auditorium, before they were really established in Nashville. There's also a nearly 15-minute tune, "I Dream the Highway," which unspools at the same meditative yoga-for-snails pace as most of the rest of their work, yet never drags. Time stretches. There's also "Elvis Presley Blues," recorded in RCA Studio B in Nashville, where Presley, of course, recorded. The song goes in part: "I was thinking alot about Elvis/Then he died, then he died." This Welch/Rawlings song would make them either time travelers or young prodigies, since Welch was still nine when Elvis Presley died, Rawlings seven.

But back to the present and "Empty Trainload of Sky." It's the opening track from the new David Rawlings & Gillian Welch album, Woodland, released August 23 on their own Nashville-based Acony Records label. They wrote all the songs. They both play guitar, and they both sing, so much so, in such tight harmony that, as they sing in the closing song, "Howdy Howdy": "We've been together since I don't know when/And the best part's where one starts and the other ends."

Other musicians do appear: Brian Allen plays bass, Russ Pahl pedal steel, and Chris Powell drums on "Empty Trainload of Sky." But you don't play with Welch and Rawlings, or Rawlings and Welch, to get noticed for your brisk solos (there really aren't any) or extraordinary chops. They're basically do-it-yourself-ers. Woodland was not only recorded at their Woodland Sound studio: Rawlings mastered and cut the lacquers, which is a tradesman's craft, distinct from that of musician. He also mastered the recordings, with the help of studio pro Ted Jensen. You can't do everything by yourself.

If I told you this was the the first studio album by "Gillian Welch & David Rawlings," it would be technically true but wildly inaccurate. Since they met in the early 1990s at the Berklee College of Music in Boston, they've been a team on records released by Gillian Welch; David Rawlings; the David Rawlings Machine (my favorite, the 2015 with the telling title Nashville Obsolete). The previous album credited to Welch & Rawlings was a 2020 live-at-home COVID covers record, All the Good Times (Are Past & Gone), which features traditional songs such as the title song and the murder ballad "Poor Ellen Smith"; John Prine's "Hello in There"; Norman Blake's "Ginseng Sullivan," (say what?), and two Bob Dylan songs: "Abandoned Love," which was recorded most notably by Doug Sahm, and "Señor," an infrequent cover from the Street-Legal album. It won a Grammy Award for Best Folk Album, one of many categories the duo both defies and identifies: there's blues, country, roots, traditional, old-timey (is that a Grammy category?) and the word I dread to use because it describes marketplace rather than music: It's very American and rhymes with banana.

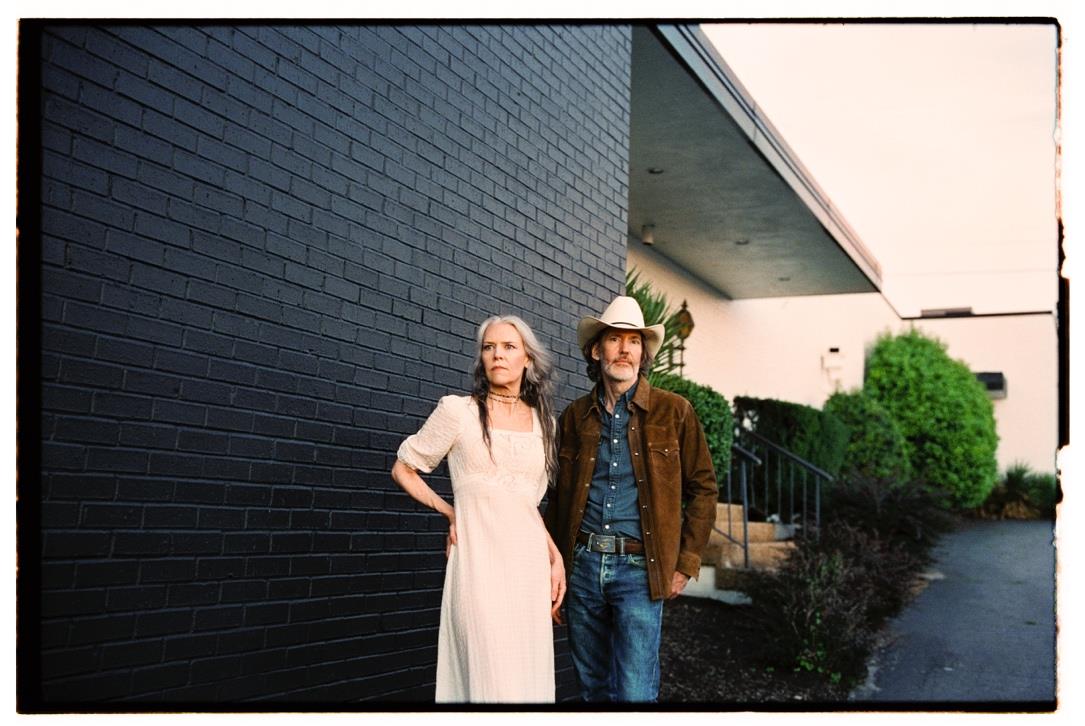

Rawlings and Welch. Photo courtesy of Berklee College of Music, all rights reserved by the copyright holder.

In early March 2020, a tornado tore through Nashville, making a direct hit on Woodland Studio, blew the roof right off. Welch and Rawlings spent a very wet, windy night salvaging guitars, recordings, equipment from the storm. Amanda Petrusich takes you inside that night in a recent The New Yorker interview. This was two weeks before the COVID lockdown. Petrusich describes them as "singing as if they have one mouth," and that again is true.

Welch and Rawlings, both class of 1992, received Berklee "American Masters" Awards in 2016. "She and Rawlings give a slow and sometimes lulling cadence to their songs, until a revelation draws out their theme," the alumni affairs office accurately wrote in its online magazine. "After graduation they moved to Nashville and began to explore the music she loved, such as Bill Monroe, Bob Dylan, and the Stanley Brothers."

Dylan plays a small but useful role in their work: They leave Dylan fragments on this album like computer code Easter eggs.

David Rawlings and Gillian Welch, Woodland, album cover.

"Here Stands a Woman" could be an excellent Loretta Lynn song, a perfect wedding tune. But it mirrors "Just Like a Woman," who "breaks just like a little girl," as Welch sings: "Here stands a woman/who was once a little girl." No matter: "It's all right ma," she sings. But no one is "only bleeding" here.

Then comes a shift, as the narrative continues: "Just like the song says . . . " and your ears wait for a cliché. But "Here Stands a Woman" continues: "Just like the song says, 'I've been around the world.'" The first thing that comes to my mind with that line is Steely Dan's "Show Biz Kids." Who knew? Fagen and Becker, wayward sons of Bill Monroe.

Then there's "North Country," no relation to Dylan's "Girl from the North Country," or is it? It's sort of geography as destiny, about a couple, unlike Dave and Gillian, destined to be kept apart by wrong time, wrong place. It gives your heart a squeeze. And "Turf the Gambler," sung by David, is clearly an outtake from John Wesley Harding that Dylan didn't bother to write or record, but he could have: it's that close to that album's vocal nuance and lyric mode.

In touch with modern slang? There's a song called "Hashtag," definitely not from the Bill Monroe catalog. (But it could be Taylor Swift’s.) You know how you go on X Twitter and see Keith Richards trending? The entire internet is ready to say Kaddish for Keith until, holding one's breath, you click and doomscroll and...Keith is still alive! (It was like that for years for Betty White, who was cut down in the prime of her life in 2021 at age 99.) So about "Hashtag": "You laughed and said the news would be bad/If I ever saw your name in a hashtag."

Sometimes they finish a song and they know it's got a problem. "The Day the Mississippi Died" is a hall of fame title. The verses roll on, muddy but unbowed, but the listener keeps hoping for something that would elevate this to "Mid-American Pie" or something monumental. Towards the end of the song, which is entirely pleasant and a good listen, David and Gillian sort of note they didn't quite nail it, didn't live up to the potential of the title. "I'm thinking this melody has gone on long enough," they sing. "The subject's entertaining but the rhymes are pretty rough." That in itself elevates the song for me: That the writers/singers have once again broken the fourth wall, and tell you what they're thinking as the song unspools. It's very intimate and inviting, as is all of Woodland, the album, and most likely the studio and the people who live and work there, too.

Header image courtesy of Alysse Gafkjen.

This article originally appeared in Wayne Robins’ Substack and is used here by permission. Wayne’s Words columnist Wayne Robins teaches at St. John’s University in Queens, New York, and writes the Critical Conditions Substack, https://waynerobins.substack.com/.