Surround sound and immersive audio are increasingly common in pop music. Do these technologies make sense for jazz recordings?

Since the late 1950s, stereo sound has served jazz well; it’s hard to argue that Kind of Blue or A Love Supreme could somehow have been better if they’d had more than two channels of sound. But now that there’s a lot of buzz around “immersive” audio – sound coming from all around the listener, even overhead – the idea of incorporating some form of surround sound has the audio production community excited. Many new pop, hip-hop and rock releases are now being released in Dolby Atmos immersive audio, available for streaming through Apple Music, Amazon Music and Tidal.

In jazz, these new technologies have been explored a bit, mostly in some immersive mixes done by Blue Note Records and released for streaming. However, these efforts have attracted much less attention than, say, Blue Note’s Tone Poet series of vinyl re-releases.

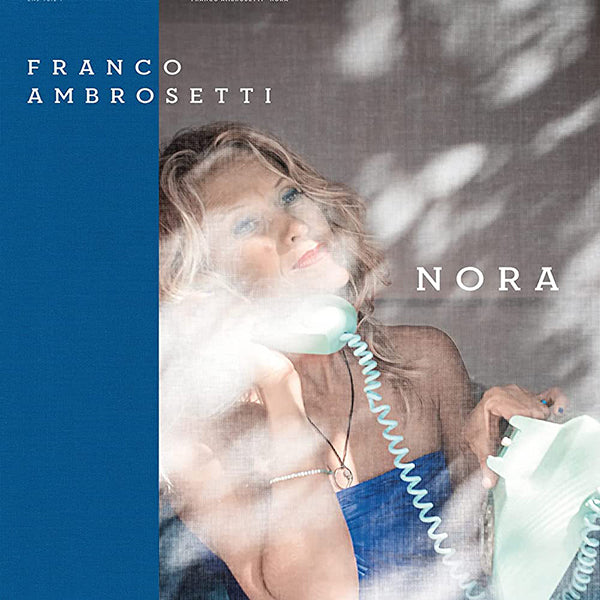

The recent release of Nora, an album by Swiss trumpeter Franco Ambrosetti that’s available in 5.1-channel surround sound in the SACD format, shows both the promise and the challenges of producing jazz in immersive or surround sound. Sonically, it’s a masterpiece – but it’s much bigger in scope than a standard jazz combo recording, and few listeners will actually get to hear it in surround sound.

As Nora producer Jeff Levenson said, “I think surround sound definitely moves the needle in terms of sound quality, but I’m not convinced that traditional jazz combo recordings will benefit, especially considering the added cost.”

Straight, No Chaser

First, let’s get our terminology straight. “Surround sound” generally refers to recordings made in “5.1,” with left, center, and right front channels; left and right surround channels; plus a dedicated subwoofer channel. “7.1” recordings add two more surround channels. Immersive audio provides even more channels, which are usually used to add a sense of height. A typical immersive sound system adds two or four ceiling speakers to a 5.1 or 7.1 setup.

However, these “better-than-stereo” formats are usually heard not through complex, multiple-speaker home theater systems where they can be fully appreciated, but through simpler systems such as soundbars, headphones or one-piece smart speakers like the Apple HomePod and Amazon Echo Studio. Immersive sound technologies such as Dolby Atmos can “map” the additional channels to play on these devices, but the simpler and smaller the sound system, the less dramatic the immersive effects will be.

A Dolby Atmos mixing studio at TVN Group, Hannover, Germany. The height-channel speakers are suspended from above. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/TVN Group.

Why Do Surround?

The idea to produce Nora in surround sound came from recording engineers Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz, who have produced previous surround-sound projects for saxophonist Jane Ira Bloom (Picture the Invisible: Focus 1, featured in Copper Issue 181 and Issue 182), vocalist Patricia Barber (Clique!), and others. The album sets Ambrosetti’s flugelhorn, guest John Scofield’s guitar, and a traditional piano/bass/drums rhythm section against the lush backdrop of a 22-piece string orchestra. This arrangement offers a lot more opportunities to place instruments around the listener in a way that’s not gimmicky. “We wanted to make it like the strings are wrapping around you, and you and Franco are in the middle,” Anderson said.

Anderson and Schwarz accomplished this not so much by “steering” specific instruments into all the extra channels, but by adding many extra pairs of stereo microphones to capture more of the studio’s ambience. “By playing with the time delays the extra microphones create, we can create a natural acoustical experience,” Anderson said. They did the stereo mix of Nora in their home in Brooklyn, and the 5.1 surround-sound mix at Skywalker Sound, the studio famous for the soundtracks of countless blockbuster movies. Anderson said he didn’t do an Atmos immersive mix because the ceiling in the studio where Nora was recorded was too low to get good ambience, but he has proposed doing a full immersive mix by effectively using Skywalker Sound’s more spacious studio as a reverb chamber, to create the impression of the musicians performing in a less-cramped space.

Money Jungle

In a genre where albums are typically recorded and mixed in a day or two, the idea of spending extra to mix and master music in immersive sound may seem unrealistic. But according to Anderson, it’s not. “The actual recording [process] doesn’t cost anything, because you’re just adding more microphones,” he said. “For the Patricia Barber project, the extra mixing for surround sound only added one day in the studio, although of course there was extra mastering time required, too. And we’ve seen at least a 20-percent sales increase when we add a surround-sound release.”

“I thought this project clearly deserved the surround-sound treatment,” Levenson said. “But as a producer, I have to ask: Do we have the money to do surround sound? Will the listeners recognize and appreciate it? And will the record company and the artist appreciate it? I don’t think that all projects are conceived equally when it comes to using surround sound. But still, I think getting better sound is always in the plus column of life, so when we can, let’s do it. Let’s adorn this music with the finest silk threads available.”

Brent Butterworth has been a professional audio journalist since 1989, and has written thousands of reviews and columns. He is currently a senior staff writer at Wirecutter. Brent previously served as editor of the SoundStage Solo headphones website, contributing technical editor for Sound & Vision magazine, editor-in-chief of Home Theater and Home Entertainment magazines, and worked as marketing director for Dolby Laboratories. He has also consulted on audio product design, tuning and measurement for major consumer electronics brands and OEM/ODMs.

Header image: Nora, album cover.