My love for the band Yes goes all the way back to my early teen years; the small town in Northeast Georgia I grew up in had two AM radio stations, which mostly played local and state news and the local farm reports. If they played any music at all, it was country, with a heavy emphasis on Johnny Cash. But by the time 1971 had rolled around, one of those stations, WGGA, allowed a Boy Scout acquaintance of mine to spin a few records after 6 pm on weekday evenings. They gave him a fair amount of leeway as far as what he played, and I’ll never forget the first time I heard “Roundabout” from Fragile in late 1971. The next morning, I ran down to the local record shop to get a copy of the 45, which was backed with “Long Distance Runaround.” Soon after, I got the Fragile LP, which stretched out “Roundabout” significantly from the three-minute radio edit. And hearing the LP version of “Long Distance Runaround” segue into “The Fish (Schindleria Praematurus)” for the first time was a thirteen-year-old mind-blowing experience!

My infatuation with Yes continued into my high school years, when, as a senior, I got my first car (‘69 Volkswagen Squareback), and bought the cheapest cassette tape deck for it that I could afford. I immediately ran over to the local Turtle’s Records and Tapes, where they had a table filled with cassettes for $3 each and bought copies of both Fragile and Close To The Edge. The CTTE cassette was molded in fluorescent pink plastic; I thought that was pretty outta site back in the day! My then-girlfriend’s birthday was coming up, and I desperately wanted her to share my love of Yes, so I got tickets to the upcoming show at the Omni in Atlanta – it was at the tail end of the Relayer tour. The concert actually occurred on her birthday, and prior to driving down to the show, I gave her copies of both the Fragile and CTTE albums. The show was beyond amazing, and intensified my mania for the band exponentially. Unfortunately, it didn’t work the same magic for my girlfriend Pam, who later told me that she found CTTE “boring.” Not long after, she announced that we needed to get married immediately, then head for Africa, where we could start saving the world by evangelizing the entire continent. That was my clue that it was time for me to move on!

I’ve seen Yes in concert multiple times over the years; of course the Relayer tour, and the “Yes In The Round” tour (which followed the release of the Tormato album) were big highlights. It was great to see Patrick Moraz with the band and hear “Sound Chaser” and “The Gates of Delirium” live, and it was especially gratifying to get to see the then-recently-returned Rick Wakeman with the band during “Yes In The Round.” But Tormato wasn’t as warmly received by both fans and the critics, and when Jon Anderson departed (Rick Wakeman also exited) to become a pop star with Jon and Vangelis in 1979, it looked like Yes was over. You can imagine my surprise when the band resurfaced in 1980 with Drama, especially minus Jon Anderson and with both members of the Buggles on board! Of course, back in those days, the only real information we got about anything going on in the music world was from DJs and Rolling Stone, so a lot of stuff happened with bands long before we fans found out – which was usually when the record was released. The Drama version of Yes splintered before the conclusion of the US tour, so hungry fans in Atlanta got…nothing. It looked like Yes was finally dead.

In late 1983, my then-girlfriend (soon to be wife) Beth and I were on a weekend getaway to Charleston, South Carolina; it was warm for November, and we had the windows down as we headed out to the beaches on the Isle of Palms. While rolling along across the causeway, this new song came on the radio; it had this kind of buzz-saw guitar intro, with a funky beat and a frenetic, jerking back-and-forth song framework. I found it pretty irresistible. But when the vocalist came in – it really sounded like Jon Anderson, but that’s not possible – Yes was a dead stick, wasn’t it? Anyway, I didn’t get to hear the DJ announce who the song was by, and it took several days to find out that it was in fact Yes, and they had a new album out, 90125. It was more rock and roll, and less proggy, and new guitarist and vocalist Trevor Rabin just killed it on all his songs. The “90125 Live” concert the following year was a definite highlight in my canon of live Yes experiences – and Beth loved the show and the band, and didn’t want to drag me off to Africa. Could it get any better?

The catalog of Yes albums that currently occupies my physical (LP, CD, DVD-Audio, and Blu-ray) and digital music server libraries is limited to everything by the band up to the 1987 album Big Generator. But my real impression of the band’s “classic” period begins with 1971’s The Yes Album, and continues through 1983’s 90125. While I do have songs from Big Generator and a recently-acquired copy of 1994’s Talk on my playlists and on the flash drive that’s attached to my car stereo, I never really dug into anything afterward. And was especially put off by all the apparent infighting and posturing among the opposing members of the band during the Anderson, Bruford, Wakeman, and Howe (1988) and Union (1991) periods. The music from that point on didn’t particularly move me, and I essentially lost interest in anything other than classic Yes.

Yes in the Compact Disc Era

My working process during the original launch and first couple of decades of the Compact Disc format was that I basically would acquire all of any particular artist’s available releases ASAP. But within a decade, everyone’s album catalog was getting remastered, and I’d sell whatever I had and get the new CDs. They were remastered; they had to be better than the originals, right? The unfortunate aspect of this is that I don’t have copies of the original CDs on hand with which to make current comparisons in terms of my impressions of their sound quality compared to the remastered versions. I only have my memory to depend upon. At that point in time, I was married with three small children, a dog, a mortgage, and two car payments – and as the kids reached their teen years and started demanding $50 pairs of jeans from The Limited at the mall, there was scarcely any money for the new releases I was interested in. I’ve always considered myself a music lover, but not really a collector, per se – I never felt the need to simply have a copy of every version of anything that existed, only the version that sounded best.

The biggest issue for me, however, is that with my current fairly high-end digital playback setup in place, I do wonder how very different my impressions of the relative sound quality of those earlier releases might be nowadays. Especially when you consider that most of the CD players I had owned from the advent of the format through the first few decades of its existence didn’t have the most robust digital to analog converters built in. I really do find that older CDs I acquire these days sound so much better on my current system than I remember them sounding back in the day. I’ve read countless articles where industry professionals involved in CD’s early phase uniformly have stated that there was essentially no problem with the 16-bit/44.1 kHz format chosen by Sony and Philips. The real problem was that the same level of playback quality found in professional equipment didn’t exist in consumer equipment of the day – consumers weren’t hearing the same thing the pros were hearing in the studio.

The first batch of Yes CDs arrived in the mid-1980s and were remastered by Barry Diament at Atlantic Studios. Of course, I rushed out and acquired every available title as soon as they were released, and pretty much determined that overall, they were a very mixed bag in terms of remastering. I’ve done a fair amount of research into this; apparently, Barry Diament, who was very highly regarded as a mastering engineer, was assigned the project, but was given very little latitude in determining which master tapes were appropriate for their initial issue in the new Compact Disc format. He was given specific tapes by the label, and was told to work with them, and some of them were very good – Close To The Edge comes to mind – but some were less than stellar (Fragile, for example). My recollection of these CDs is that they were pretty ho-hum, and I ditched them quickly for the next batch of remastered releases.

These came in the early ’90s, and were handled by Joe Gastwirt at Oceanview Digital. Gastwirt was developing quite the reputation for his remastering skills. The CDs came with booklets with more photos and extensive liner notes than the original releases, and on the surface appeared to be a big improvement over the originals. However, Gastwirt did use some compression when preparing the newer remasterings, and he employed a certain level of a relatively new process called “NoNoise” that was touted to eliminate any hiss while retaining all the original’s dynamics. I don’t actually believe NoNoise worked as well as Gastwirt and company believed it did, and my recollection of the sound quality was that it wasn’t significantly (if at all) better than the Barry Diament discs, and in some cases, maybe even worse. My online research has proven that I’m not alone in this – hardly anyone else really loved the Gastwirt reissues either.

2003 brought the latest incarnation of Yes reissues, which were produced by Rhino with Dan Hersch and Bill Inglot at DigiPrep handling the remastering chores. The first batch of these reissues initially came in deluxe Digi-paks, with full-album-art outer sleeves and fold-outs that replicated the original album packaging. These reissues include essays from writers at the YesWorld website, along with a selection of previously-unavailable photos, and complete album lyrics. Many of the discs included a substantial number of previously unreleased bonus tracks. For catalog CDs, these seemed to be the gold standard! Of particular interest to me was the reissue of Tales From Topographic Oceans, which restored a couple of minutes at the beginning of “The Revealing Science of God” that had been trimmed from every previous known release. Unfortunately, the overall sound of these reissues has been described as Bill Inglot’s “house sound,” which has the vocals very forward in the mix, with an overly-bright treble response. I guess a lot of what you’ll ultimately hear is system dependent – horns or compression-driver loudspeakers probably wouldn’t be a good choice for playback of these albums. Despite the fact that these versions are less-than-perfect, they still currently sit on my CD shelf, although where possible, most of my listening is done with higher-resolution versions.

The most notable other set of Yes CD releases came from Japanese label East-West, which released HDCD versions of classic titles. When these first appeared there was scant information regarding the provenance of their source tapes, and numerous complaints about the sound quality. And the prices seemed high, though not especially so for a Japanese import. With all the seeming negatives and their relatively limited availability, I never pursued any of them. The general consensus still seems to be that the sound quality didn’t measure up, or wasn’t significantly better than anything else that was already out there. And of course, there are the SHM CDs, which are also expensive Japanese imports. The big selling point of the SHMs is that they’re made from a super-high-density polycarbonate material, which is supposed to greatly enhance their optical properties and improve playback. Since these are 16-bit/44.1 kHz CDs, I also decided to opt out and wait and see if any of them were ever released as SHM SACDs – I own a few discs from this label and they’re excellent (if expensive). So far, no dice.

Yes In High-Resolution Digital

In the last few years, I’ve gotten my music server/streamer setup dialed into something approaching affordable perfection, and I’ve also had a renewed interest in exploring Yes releases that are now available in higher-resolution digital formats. To name a few: 24-bit/192 kHz digital downloads from HDTracks, remixed and remastered 24-bit/96 kHz versions from Steven Wilson that are available on both Blu-ray and DVD-Audio discs, and a handful of SACD disc titles from the now-defunct Audio Fidelity label. Not all of Yes’s catalog titles have been made available (so far) from any one of these sources; the selection at HDTracks is probably the best in terms of number of catalog Yes albums currently available. As of this writing, the Steven Wilson remix/remasters are limited to the five consecutive studio albums running from The Yes Album through Relayer. While Audio Fidelity had released a number of Yes albums as gold CDs, I’ve only been able to determine that two SACDs were ever released by the label – Close To The Edge and Going For The One.

The higher-resolution HDTracks downloads range in price from around $22 to $28, depending on the album and choice of resolution. The Steven Wilson remix/remasters originally retailed for around $20 for the DVD-Audio/CD packages, and around $30 for the Blu-ray/CD sets. But they haven’t been re-pressed in several years, and the prices online have been climbing, especially for the BD/CD packages – I’ve seen them selling on Discogs and eBay for as much as $100 recently. The Audio Fidelity SACDs, while originally retailing for around $30, are long out of print and now demand anywhere from $60 (GFTO) to $100 (CTTE) at online resellers. The HDTracks pricing has remained consistent for several years, but the DVD/BD/SACD disc pricing has gone berserk, especially over the last six months. The cost of many of the discs have more than doubled, and some of them even aren’t even available anymore at any price.

Next time, I’ll talk about the remastering approaches of the various parties and labels involved, and how the digital download and disc versions differ from one another. Till then, Happy trails!

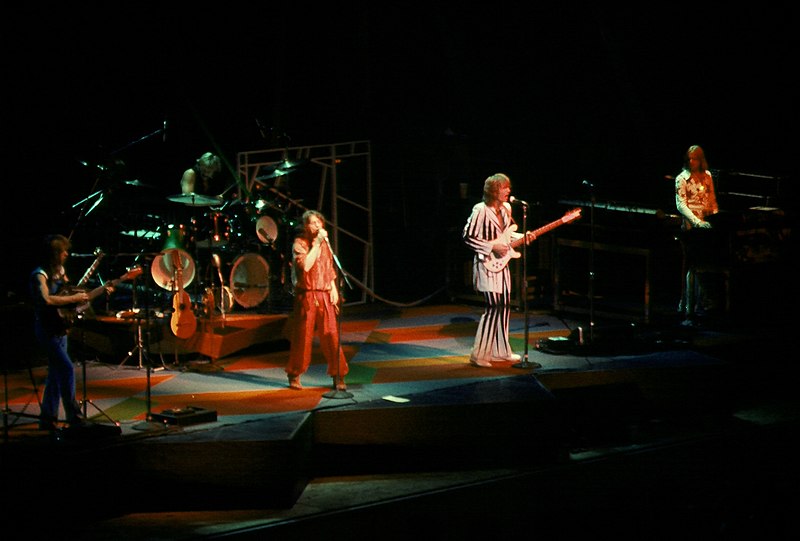

Header image: Yes, courtesy of Wikipedia/Rick Dikeman.