Not so long ago, businesses lived and died by the price tag, that sticker affixed to an item served as a contract between the customer and purveyor. But what if price tags were mere suggestions? What if clothes at your local department store fluctuated by week, day, and even by the hour, or the corner diner charged more for a burger on Saturdays and even tacked on fees for that cozy booth by the window? It would be a scandal because consumers have relied on transparent pricing for over 150 years.

Quakers are credited with the first price tag, which was a way of ensuring fairness and equality – everyone paid the same price for the same item. John Wanamaker of Philadelphia, founder of one of the first department stores in America, instituted the systematic use of price tags to end haggling by sales clerks. Store price tags were also a way of honoring the customer, their money, and ensuring return business. But the marketplace has changed, and we have become accustomed to ever-changing prices whenever we shop online, especially for concert tickets.

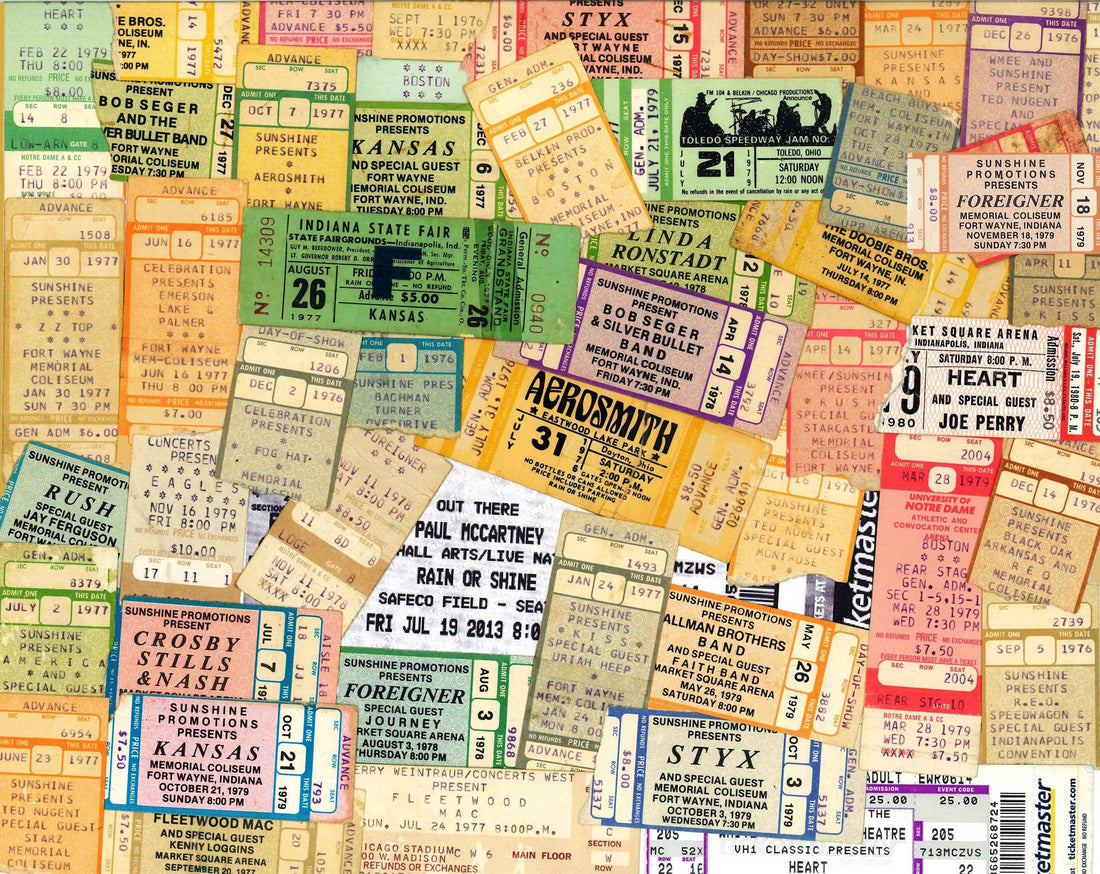

Today, buying tickets is like a hostage situation at an auction house, but in the 1980s, when I went to shows, tickets cost between $10 and $30. Supply and demand was a tangible concept that could be judged by arena capacity and the number of people lining the sidewalk to buy tickets. Although purchasing tickets took some effort, it was generally on the first-come, first-served business model, with fans and scalpers alike queuing up for hours before the box office opened.

Waiting in line was fine for teenagers, but those with regular day jobs could visit one of the many Ticketron counters for a small fee split between the venue and fan. People with no other options had to buy expensive tickets from brokers, so we all welcomed the evolution in convenience when Ticketmaster started offering phone sales and, eventually, online purchasing. Ticketmaster became the favorite platform because it returned a portion of the customer fees to the venue. By the turn of the century, Ticketmaster was already selling billions of dollars in tickets, and ever-increasing fees were a powerful incentive to do business with the ticketing giant.

Courtesy of Pexels.com/Wendy Wei.

Newer online platforms make it possible for everyone everywhere to buy and resell with just a few keystrokes. It sounds remarkably democratic and fair, but the original face value of tickets – the price tags – have now been replaced by surge pricing (politely known as “dynamic pricing”), legal scalping, and fees that range a wide swath starting at around 15 percent of the final ticket price. For example, tickets for the high-demand Beyoncé show at MetLife Stadium range from a stage-side VIP seat for $3,757 plus $561 in fees, to the cheapest non-reseller option, an official Platinum ticket (one that is set aside by the artist and sold at market value), which commands $711 plus $110 in fees for a seat on the 200 Level. The cheapest resale ticket at the farthest reaches of the stadium is $299, including $50 in fees.

Contrast those prices with the upcoming Misfits show at New Jersey's Prudential Center, with floor access for $309 and the cheapest seat in the last row at $67, fees included. Seats in the middle section range from $150 – $300, which seems entirely reasonable compared to Beyoncé, but for old-school punk rockers weaned on seeing bands in sweaty basements for a few bucks, these prices are still excessive and exploitive.

If you're like me and prefer sitting on the aisle, you are often required to buy a minimum of two seats. Whether you want it or not, the empty seat is your problem. You can sell that extra ticket through a reseller for a potentially healthy profit, which seems like a lucrative option at first, but more fees await for a ticket that might not sell if demand wanes. The venue doesn't care because they've already made their money, but hundreds, maybe thousands, of ticket holders are flooding the open market with inflated prices and creating artificial scarcity.

In the meantime, concert-goers have been convinced that they’re just sharing the increased financial burden of putting on live shows. Justifications cite high costs of wages, travel, and gear, but rarely do we get an accounting of the profits to bands, promoters, arenas, and ticket sellers. Fans appreciate that musicians have all but lost their revenue due to streaming and need to recoup more money from touring, merch, and meet and greet experiences.

Personally, I want rock stars to be rich and luxuriant in shiny new Rolls Royces and leather pants. Still, I shouldn't have to fill the pockets of ticket middlemen who leave concertgoers scrounging for fewer face-value tickets that haven't been gobbled up by reseller bots, or Platinum tickets and "hold back" tickets given to band members, affiliates, promoters, record labels, assorted VIPs, and anyone else involved in mounting the show. Unsurprisingly, hold-backs have become another revenue stream, as well-situated tickets are funneled onto the resale market where they're priced to the highest level the market will bear.

However, the resellers are only part of the problem. When a single, global, multi-billion dollar company manages acts, owns multiple venues, and operates the biggest ticket platform in the world, fans and bands are trapped in the same system. Even if a band wanted to circumvent Ticketmaster, they risk being relegated to the least-desirable venues in out-of-the-way locations. Ultimately, fans pay the price.

Now young people need to rely on their parents to pay for concerts with A-level stars. I'm willing to bet that few teenagers are seeing major acts on a regular basis. The paycheck from my part-time job in high school was enough to pay for all my shows. I attended concerts nearly every month and saw new bands on a whim – Metallica, Stevie Ray Vaughn, U2, and John Mellencamp, to name a few. A single Taylor Swift or Harry Styles ticket could have funded my entire concert-going career.

The current marketplace also sidelines many lifelong fans who have supported artists and the music industry for decades. For the last chance to snag a decent seat at a classic rock show, they’re expected to drain their retirement accounts. At the moment, a pair of Bruce Springsteen floor tickets at the Prudential Center cost $5,100, plus $1,175.95 in fees, with optional cancellation insurance for $470.70, for a grand total of $6,746.65 for a night out. As our editor, Frank Doris, noted, "You might as well buy new stereo equipment."

Bruce Springsteen at the Climate Pledge Arena, Seattle, Washington, February 2023. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Dharmabumstead.

Bruce Springsteen at the Climate Pledge Arena, Seattle, Washington, February 2023. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Dharmabumstead.

How can this unbridled system be fixed, short of government intervention? One answer: bring back the price tag. Allow the band, venue, and promoter to preset a range of fixed prices and make tickets completely non-transferable, unless it's through an official face-value ticket exchange program. Then, reduce the number of hold-backs and sell unclaimed ones exclusively through the venue at face value. Bands could still profit from premium seats, the venue and promoters get their cuts, and fans get fair access to more affordable seats. This solution does not necessarily halt dynamic pricing but it essentially shuts down the hyper-inflated resale market and provides a more accurate picture of the real demand. Nevertheless, with millions of lobbying dollars, the existing structure will not change any time soon – there’s just too much money flowing.

If you're still going to concerts, here are a few tips for getting the best deals:

- Buy directly from the venue's on-site box office as soon as tickets go on sale.

- Join the band's fan club and look for a presale code.

- Attend a show by a popular band in a smaller market.

- Ask your credit card company if they offer a ticket program.

- Buy a ticket on the day of the show or, better yet, wait till show time when desperate resellers are dumping tickets.

My last tip: plan your show schedule carefully if you're on a budget. As much as I want to see the Misfits, The Cure, and Depeche Mode, I can't afford all three, especially if dynamic pricing is a factor.

At this point in my life, I'm more likely to skip shows than attend them. I've seen most of my favorite bands, and I'm not keen on spending hundreds of dollars to see new ones, or geriatric retreads of nostalgia acts. Indeed, my absence from the show will be inconsequential, but my wife, once an avid concert-goer, is not going either, and our friends are attending one A-list concert per year. Our refusal to participate in fees, greed, and price gouging will certainly become consequential if more people follow this trend. Then there will be no more concerts, let alone profits. Just a little something for the industry to consider.

Header image courtesy of Pixabay/PublicDomainPictures.