In the previous episode (Issue 181), we had a look at various types of analog-domain reverberation options for music production and recording. A couple of years back, during the “big move” (documented in Copper Issues 131 and 132) of my studio facility and workshop to a much larger building, as necessitated by rapid growth of the business and possibly prompted by the highly reverberant sound environment of a large empty building as the various rooms were being acoustically treated and insane amounts of stuff was being brought in, which resulted in a drastic reduction in the original reverberation of the empty shell, I was contemplating these issues. (An even bigger move may be in our future, as business has continued to grow to the point where we are now beginning to outgrow the building we had hoped would be big enough for a while.)

It was a historical contemplation, influenced by my observations of the acoustics of the new building, along with my experience of designing and constructing studio and laboratory facilities in different types of buildings in different countries, and of course my experiences with conducting recordings in different studios and on location over the years.

By the end of the move, I had decided to build a custom stereophonic reverb unit, exactly as I would want it for my own personal use, without much thought being put into the aspects of product marketability and perhaps even more importantly, pricing. I had a particular idea of what I wanted to do and was well aware from the onset that this would not be a marketable product that anyone else would ever want to buy (or so I thought). With that in mind, having often experienced the pressure of needing to conform to what the market would deem acceptable and reasonable, I felt fully at liberty to explore the outrageous, unreasonable and to some, even unthinkable in the present day. I simply wouldn’t have to worry about any of that. I had decided to design and build something that would only ever find application within my own facility, by myself and other like-minded individuals, who, contrary to “normal” people, have decided that practicality shall not be allowed to intrude into a creative workflow.

As stated in the previous episode, I have yet to encounter any form of artificial reverberation that could convincingly replace natural reverberation. If my goal in a recording is to capture natural reverberation, I can think of many places with outstanding natural acoustics where I can do that. There are very few things I hate more than a mediocre attempt at emulating something. That’s why I also firmly believe that if you want to capture the sound of a grand piano, you need a grand piano, a really big, heavy grand piano. Along with someone who knows how to tune it and service it. Yes, it is impractical and inconvenient, not to mention more expensive than your cheap plastic MIDI keyboard with a Concert Grand preset.

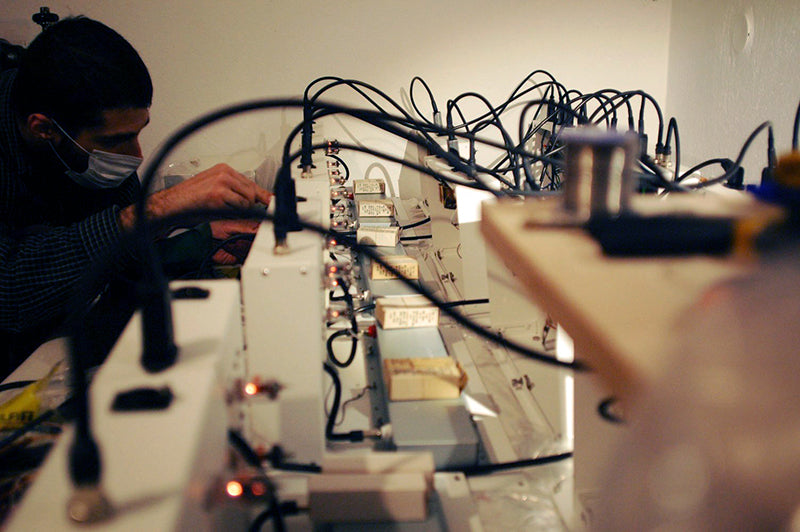

Vacuum tube spring reverb units being assembled at the Agnew Analog Precision Engineering Laboratory.

Don’t get me wrong; you can play with cheap plastic things in your bedroom all you like. But if you decide to conduct a recording, you are forever capturing something that is presumably worth preserving throughout history, defining a cultural heritage for future generations. If you really believe you do actually have something truly worthy of preservation, then do it properly. Get a grand piano if you have to, get a real Moog Modular synthesizer, get a good guitar, get a good drummer, or even get a Roland TR-909 drum machine if this is the type of music you are trying to make. But never forget that a Roland TR-909 is not a replacement for a drummer; it is an entirely different sound that defined an entirely different style of music where drummers are entirely absent. I am not judgmental about styles of music. I can appreciate the entire range from Whitehouse to Vivaldi, but whatever it is that you do, do it properly.

To illustrate this point even further at the risk of using a rather graphic example, Luces Abela, performing as Justice Yeldham, played a piece of broken glass as a wind instrument, often sustaining injuries on stage, much to the excitement of a bloodthirsty audience, perfectly representing the state of the world we live in. But he was using the highest-quality contact microphones one could buy, originally intended for piano recording, and which came in a very elegant-looking wooden case.

There are many wonderful, unique sounds created through the use of synthesizers and electronic keyboards. The Hammond organ (to return to our reverbly path) has established itself as its own genre with its unique, instantly recognizable sound. It is not a lower-cost replacement for a grand piano, nor will a cheap MIDI keyboard ever be a convincing substitute for a Hammond or a concert grand, nor will anyone ever make a grand if they can’t be bothered to use a real grand or a Hammond where needed. Likewise, I am not going to even attempt to make a bad emulation of a real acoustic space. That’s what real acoustic spaces are for.

Top view of a vacuum tube spring reverb unit.

If you need one, you need one. Much like the Hammond organ (whose creator, Laurens Hammond, was also the originator of the spring reverb concept), I see artificial reverberation as a genre in itself. It has defined certain styles of music, the whole spectrum from the good to the bad to the ugly.

Even though I personally absolutely hate it, who can argue that the incredibly fake-sounding and grossly exaggerated early digital reverb units, liberally applied to the “grand canyon snare drum” sound of ’80s pop music, did not define an entire era? Similarly, plate and spring reverb units have become embedded in various musical styles and time periods (for example, spring reverb and surf music) to the same extent that concert hall acoustics have defined Western classical music recordings.

In the next episode we will have a closer look at the design of these reverb units.

Vacuum tube filaments glowing in the dark during testing.

Header image: J.I. Agnew building the custom vacuum tube spring reverb units. All images courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments.