By the 1970s, disk recording had pretty much disappeared from all sectors, with the sole exception of cutting masters for the industrial manufacturing of vinyl records. Radio stations had moved to magnetic tape recording and so did the small recording studios that would, in earlier decades, record artists direct to disk, using a single microphone. The motion picture industry had developed elaborate systems that would allow film cameras to be synchronized with tape machines, gradually weaning from disk recording lathes as well. With the introduction of cassette tape, dictation, logging of information, promo copies of recordings, band copies, and various other applications all moved away from the disk medium. While the vinyl record was still king among consumer media and professional disk mastering lathes were still in production and active development, an entire sector that had been manufacturing lathes that were less-sophisticated, and primarily intended for cutting one-off records rather than masters for subsequent plating and pressing had pretty much collapsed.

Lathes for cutting one-off records had always been much more plentiful than those intended for mastering. There were many more manufacturers all around the world and their products were made in much larger numbers than mastering lathes. Although any lathe could technically be used to either cut masters or to cut one-off records, mastering lathes were usually much larger, and offered more features and a higher level of performance. While noises and speed instability may be tolerated on a one-off recording (especially when this was only done to comply with various legal requirements, such as regulating authorities’ requirements for radio stations to log their output, and it was expected that nobody would ever listen to the result), the expectations were much higher when a master disk would be cut, which would be used to manufacture several thousand identical copies, the sound quality of which at best would only ever be as good as the master. As such, mastering lathes were designed to offer a much higher level of sound quality and as this was (and still very much is) easier said than done, they were priced accordingly.

The 1970s was the decade during which only five companies were left in the entire world that were manufacturing disk mastering lathes and electronics: Neumann, Scully, Lyrec, Westrex and Ortofon. Companies such as Presto, Rek-O-Kut, Fairchild, RCA and several others had either folded, or left the disk recording sector. Very few lathes were still being manufactured and sold to cater for the needs of the vinyl record manufacturing sector. The attempts of the 1940s to introduce a consumer-oriented sound recording device that would be based on grooved disks had long been abandoned in favor of the much simpler process of recording on tape, which proved much more compatible with domestic environments than the oily machine tools of yesteryear. After all, the average consumer is supposed to want something that is easy to learn and simple to do. Very few out of many cassette deck owners ever managed to do a high-quality recording on tape, and even fewer owners of consumer-oriented disk recording lathes ever got anything decent out of their machines.

Tape was much easier to deal with and carried a substantially lower risk of damaging expensive equipment (cutter heads) or personal injury (the recording blanks were made of nitrocellulose lacquer, the same material as modern smokeless powder for firearms ammunition).

Strangely, given the introduction above, it was during the 1970s that Japan reintroduced the concept of the consumer-oriented disk recording lathe, even though they were already leading the cassette market. Despite the complexity and precision manufacturing requirements of disk recording lathes, it was not the big players that were behind the newly-introduced lathes.

The Hararokuonki Saitama company in Tokyo introduced a few different models under the Hara brand name, built into suitcases for portable recording. They had everything built in, so all you needed was a supply of blank disks and a microphone or a line signal from another audio playback device. The Hara Disk Recorder M-180 was a very small and portable disk recording lathe, with a 7-inch platter that would spin at 45 rpm.

Two Hara M-180 disk recording lathes with Agnew Analog Type 1765 power supply units, which allow them to correctly function with European power (230 VAC/50 Hz). Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments, photo by Sabine Agnew.

It was idler-driven and the motor would lock to the powerline frequency, which in Japan was 100 volts AC at 60 Hz. If used in Europe or other parts of the world with a powerline frequency of 50 Hz, even through a step-down transformer to ensure that the correct voltage would be applied, the motor would run at the wrong speed.

The only cure was to modify parts of the mechanism, so that it could spin the platter at the correct speed at 50 Hz. Portable though it may be, there were still geographic limitations to the machine’s portability, in the form of the requirement for power of the correct voltage and frequency.

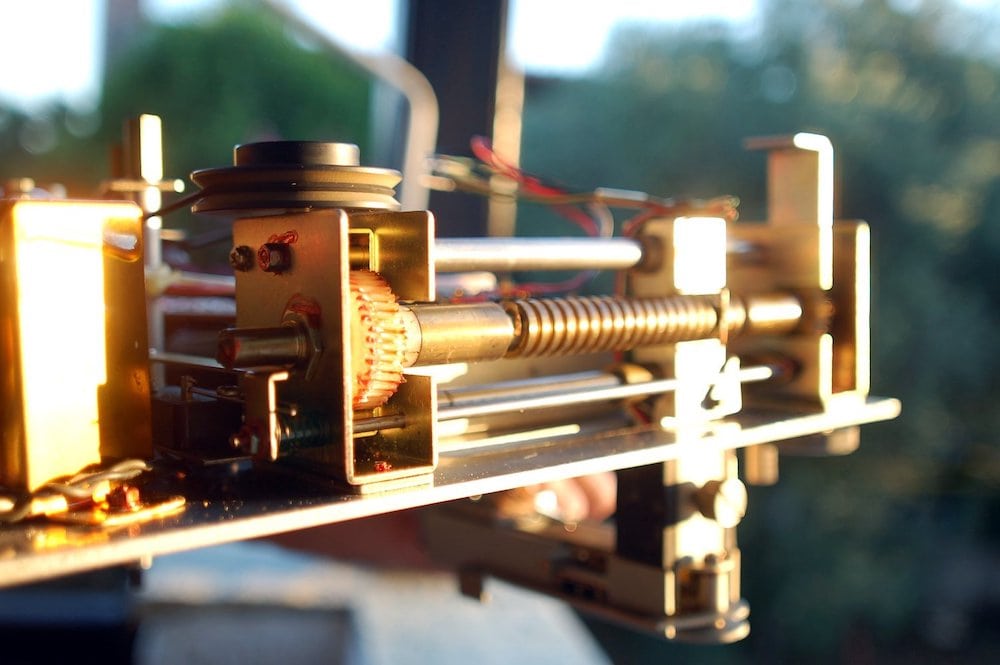

The leadscrew is belt driven from the platter spindle and advances the carriage by means of a disengageable piece of wire, rather than a more conventional half-nut. The cutter head is a monophonic moving iron design, covering a frequency range of 50 Hz to 8 kHz, +/- 3 dB, according to the screen-printed text, partly in Japanese and partly in English, on the machine itself. The same text also claims that the machine will operate at 100 V, 50-60 Hz, and while it indeed will operate, it won’t be at the correct speed, unless the correct frequency is used.

The leadscrew mechanism inside a Hara M-180. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments/Sabine Agnew.

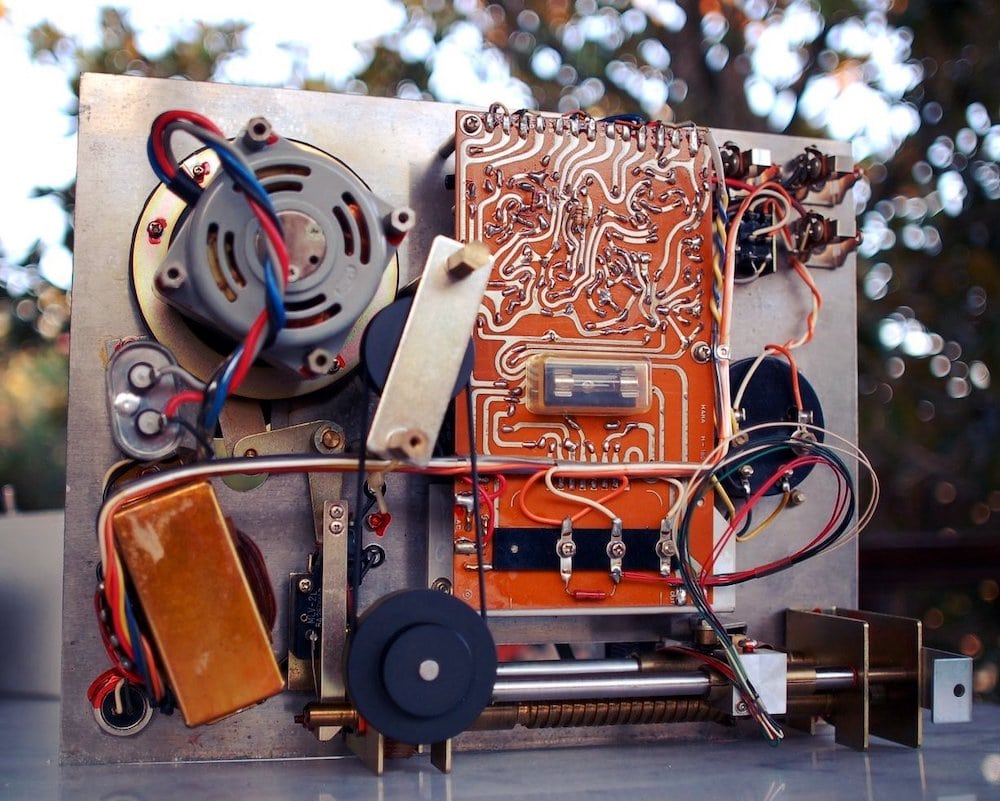

The underside of the Hara M-180: motor, main bearing and pulley, cutting amplifier printed circuit board, power transformer, carriage, and leadscrew. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments/Sabine Agnew.

Motor capstan, idler wheel and bearing spindle on a Hara M-180. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments/Sabine Agnew.

Two Hara M-180 disk recorders with Agnew Analog power supply units, undergoing final assembly and testing upon restoration on the patio at Agnew Analog headquarters. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments/Sabine Agnew.

The blank record is held down by means of a clamp that screws down on the spindle. The platter automatically starts spinning as soon as the carriage arm is manually advanced to the starting diameter of the 7-inch record. A hand crank on the side of the machine actuates a pair of bevel gears that advance the leadscrew to create spirals between the selections, and lead-in and lead-out grooves.

There is a lever provided on the side of the carriage arm for lifting and dropping the head and a little lever to adjust the depth of cut, along with a small brush to keep the chips out of the way of the cutting stylus.

The very basic built-in audio electronics included a microphone preamplifier, a phono stage for plugging in a separate playback turntable to check your cuts, a line amplifier for line-level signals (whatever this may mean in terms of signal level), level control knobs, and even a VU meter! All within the space of a lightweight suitcase that measures approximately 14 x 10 x 7 inches! In the 1970s, this was probably the smallest disk recording system ever made. The sound quality was as would be expected of a system of such dimensions; not exactly stellar!

VU meters, inputs and controls, along with the carriage and cutter head, on a Hara M-180. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments/Sabine Agnew.

However, the serial numbers on the various examples I have personally encountered to date would suggest that over 1,000 of these little devices were manufactured and successfully sold. Despite efforts made to screen-print information in English on the machine itself, and in the manual, it appears that these units were originally only sold in Japan. By now, they are being exported all around the world and converted to run from the power available where they are being operated.

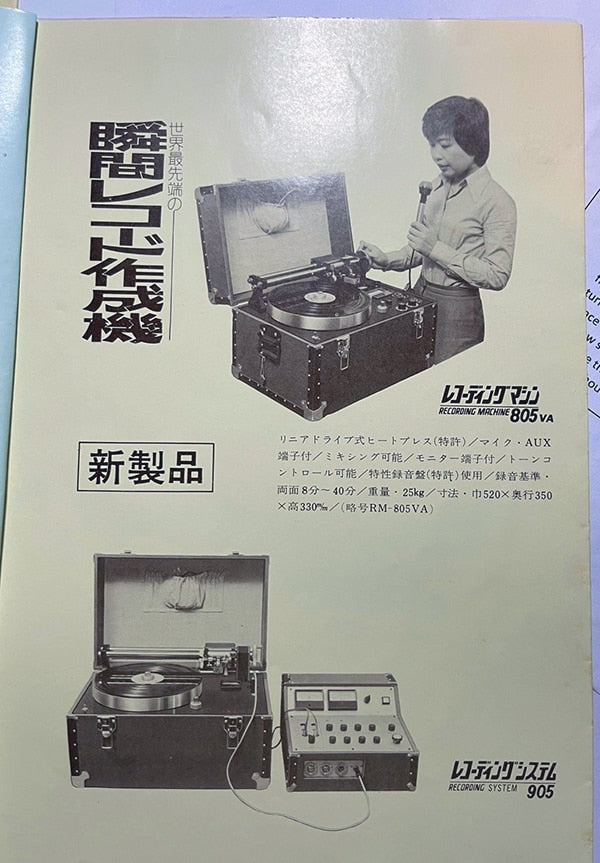

To complement the Hara Disk Recorder M-180, a larger version was introduced, the Hara Recording Machine 805 VA. This was very similar to the M-180, but with a 12-inch platter and a sturdier carriage running on guide rails. When purchased along with an additional suitcase holding the audio electronics in the form of a more elaborate mixing board (instead of the built-in audio electronics of the M-180 and the basic 805 VA), it was known as the “Recording System 805.” The RM-805 VA measured approximately 20 x 14 x13 inches and weighed a bit over 55 lbs. The voltage and frequency situation were similar on the bigger Hara.

The Hara 805 VA disk recording lathe at Groovefarm Analog Recording Company, in Heath, situated in the picturesque countryside of the Peak District in England. Courtesy of Liam Walker.

A Hara 805 VA disk recording lathe and associated recording equipment in the studio. Courtesy of Liam Walker/Groovefarm Analog Recording Company.

Japanese brochure for the Hara 805 VA recording machine and the 905 Recording System. Courtesy of Liam Walker/Groovefarm Analog Recording Company.

Very few of these are still around nowadays, so I assume they were made in much smaller numbers than the M-180.

In the next episode, we will be looking at the other offerings of disk recording lathes manufactured in Japan.

Header image: Two portable Hara M-180 disk recorders with Agnew Analog power supply units, undergoing final assembly and testing upon restoration on the patio at Agnew Analog headquarters. Courtesy of Agnew Analog Reference Instruments, photo by Sabine Agnew.