Ever since my grandmother Edna gave me a transistor radio for my birthday in 1964 just in time for Beatlemania, I was mesmerized by gadgets that emanated sound. By the sixth grade, I graduated to a cassette tape recorder (I actually was looking for a mini reel-to-reel, but Korvettes didn’t sell any) and a few years later my first record player. By the mid-1980s, I made it to the CD, which, by the late 1990s, hit its peak, and accounted for the best job I ever had.

I was reminded of my love affair with electronic gadgets when in early September I visited the Philips Museum in Eindhoven, The Netherlands, a country where most tourists’ idea of culture would be going to Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum (went there on my first European trip in 1983), the Anne Frank House (tried to get in this time but tickets were sold out), or the Rijksmuseum, the national showcase of Dutch art and history.

But Copper readers no doubt would view the Philips Museum the same way I did, like a kid in a candy store. Seeing the vintage equipment behind glass showcases make you want to twist the knobs of some nearly century-old shortwave radios and early record players to see if they still work.

Laid out chronologically on three floors, the museum traces the 130-year-old company’s history of bringing entertainment to people’s homes, and as a consumer electronics innovator. Founded in Eindhoven in 1891, Philips’ first industrial product was the light bulb. (An English inventor had debuted the concept in the early 1800s, and Thomas Edison commercialized light bulbs in the US by the late 1880s.) Philips’ laboratory soon led to groundbreaking inventions, as the facility went on to become one of the leading research centers in the world. Medical breakthroughs starting in 1924 through 1932 centered around the company’s X-ray tube, which helped diagnose tuberculosis. As a result, TB cases were lower by 60 percent in Eindhoven than elsewhere. The company manufactured its first radios in the 1930s.

Above: an assortment of early radios and record players.

Philips introduced the electric razor to Europe in 1939; in the US the brand name for the device became Norelco. With the outbreak of World War II, just prior to the Nazi occupation of The Netherlands, company founder Anton Philips and family members fled to the US. Meanwhile, the Philips radio factory in Eindhoven was badly damaged after being bombed by the Royal Air Force. Presumably, German forces were firing at the Allies’ planes from atop the Philips building. WWII is also mentioned among the museum’s exhibits by a 1997 “Certificate of Honour” from Israel acknowledging the courageous work the company did in protecting Jews from the Nazis.

The Certificate of Honour given to Philips.

While Philips previously was one of the largest electronics companies in the world, it currently is focused on its healthcare efforts. But I came to the museum more to soak up the vintage turntables and tape recorders running on tubes and transistors, as you can see from photos in the article.

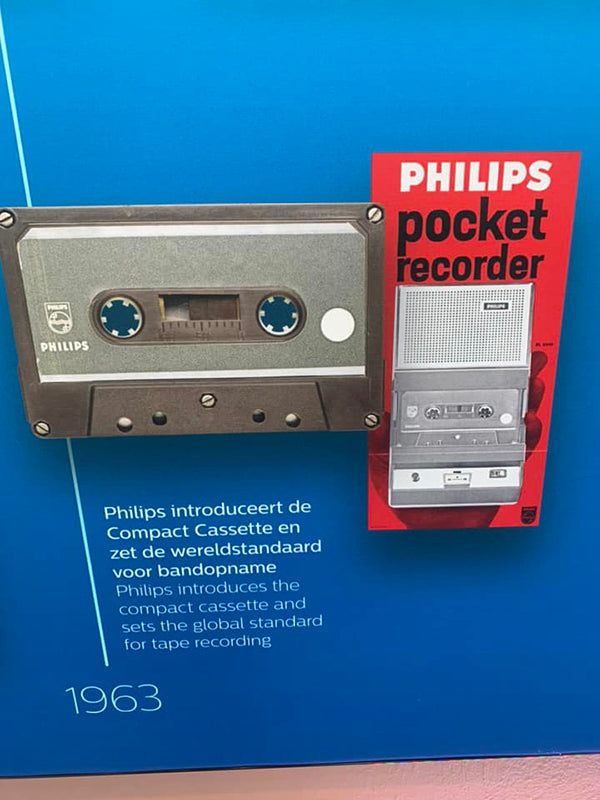

Philips invented the compact cassette in 1963, for which it still takes great pride, as demonstrated by a recent documentary I recommend called Cassette, available on Showtime.

A circa 1963 Pocket Recorder cassette player.

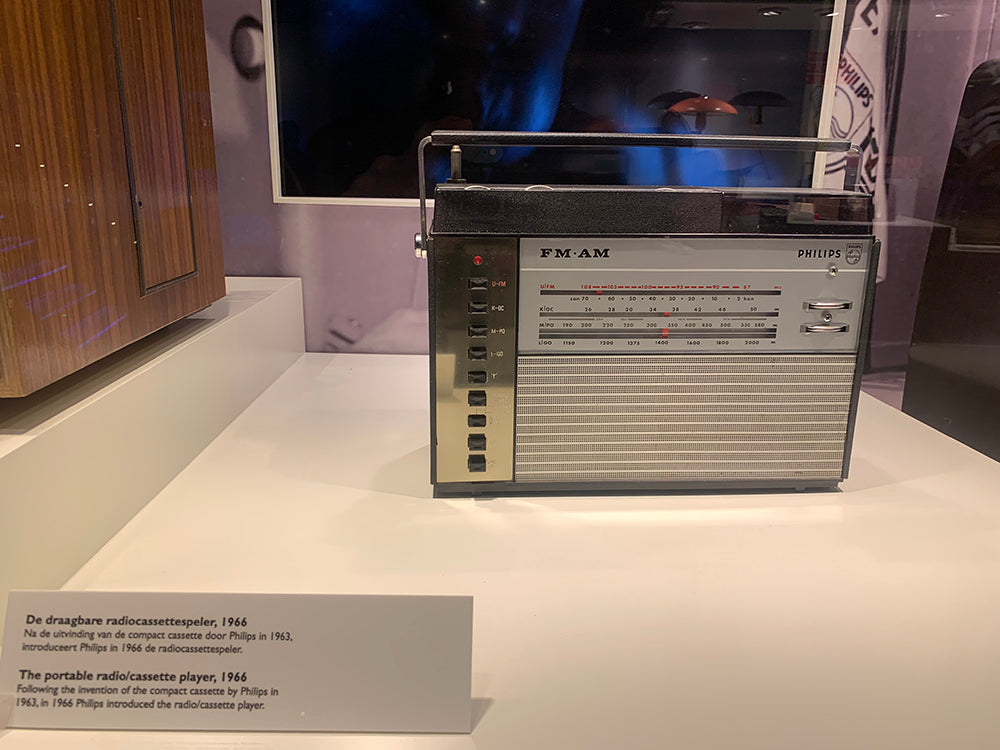

A 1966 portable radio/cassette player.

As a vertically integrated company, Philips saw the importance of owning the hardware and the software, in 1950 forming Philips Records, later including such imprints as Fontana, Mercury, and Vertigo. Depending on the territory, Philips-affiliated artists included the diverse talents of Big Bill Broonzy, Dave Van Ronk, Nina Simone, Dusty Springfield, the Walker Brothers, Serge Gainsbourg, Black Sabbath, Uriah Heep, the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, Graham Parker and The Rumour, Dire Straits, ABC, and David Bowie. In 1962, Philips Records became a major player in the classical music world by forming a joint venture, the Grammophon-Philips Group (GPG) with powerhouse Deutsche Grammophon, which became Polygram in 1972. Polygram was acquired by the Universal Music Group in 1998.

One very special exhibit is Philips’ first laser-read video disc player, which the company had been working on since the early 1970s, and which served as a precursor to the compact disc and later DVD. Philips debuted the compact disc at a press conference in 1979 in Eindhoven. Avoiding what could have easily become a format war, Philips ended up partnering with Sony to introduce the CD, which the museum highlights with a display of Dire Straits’ Brothers in Arms, released in 1985 on Warner Bros. in the US and internationally on Vertigo.

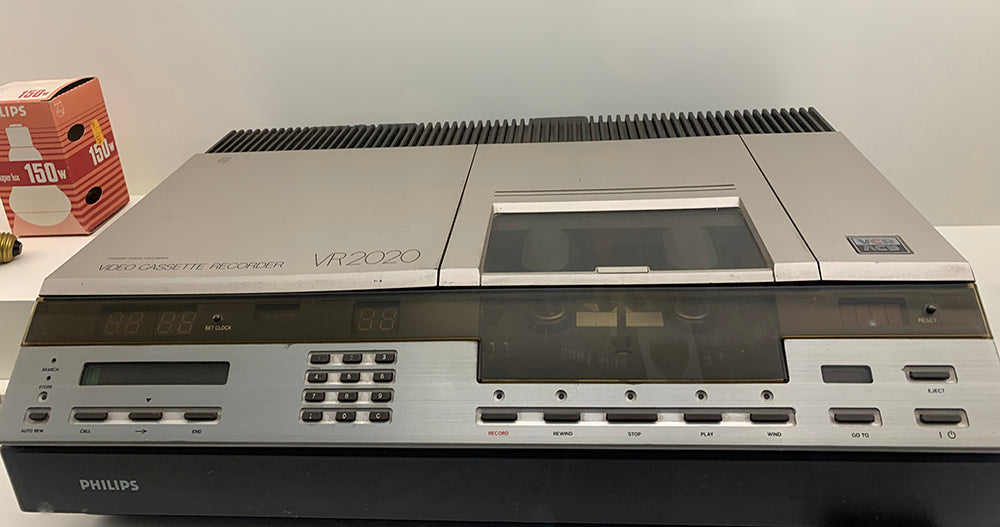

An early VCR.

The CD format launched in Japan in October 1982 and in Europe in March 1983. The Philips CD-100 was the second commercially released CD player, after Sony’s CDP-101.

In 1980 Philips acquired the venerable hi-fi brand Marantz, based in Kanagawa, Japan. In 2002, Marantz Japan merged with Denon to form D&M Holdings. Philips sold its remaining stake in D&M Holdings in 2008.

If I could come home with one showcase item from the museum, it’s a toss-up between one of the early radio/record player combos, or the wall-sized blowup single of Bowie’s “Space Oddity” resting on the couch.

Who wouldn’t want this 1987 Moving Sound cassette player?

Or this Moving Sound CD boombox?

A larger-than-life 45 RPM single of David Bowie’s larger-than-life “Space Oddity.”

Too bad the gift shop didn’t sell any electronics. I might have been tempted by a transistor radio, portable record player, or tape recorder.

Portable transistor radio, circa 1957.

A 1970s circular record player.

Philips had portable reel-to-reel enthusiasts covered.

Spotted at a local bookstore.

Copper contributor Larry Jaffee is author of the book Record Store Day: The Most Improbable Comeback of the 21st Century. Jaffee was editor of the CD/DVD production trade magazine Medialine from 1998 until 2005, and is co-founder/conference director of industry trade organization Making Vinyl. More information is available at www.larryjaffee.com.

Header image: a Philips shortwave radio. All images courtesy of Larry Jaffee.