There was a message for me to call Dan Meinwald early this afternoon, December 17th. I didn’t think for a second the news would be what it was.

Tim de Paravacini is dead, of Stage IV liver cancer, in Japan.

I was just messaging with him last week, ironically about the health of someone we both care about. I thought he was doing at least as well as me. (Which ain’t so great, but I’m not dead yet…).

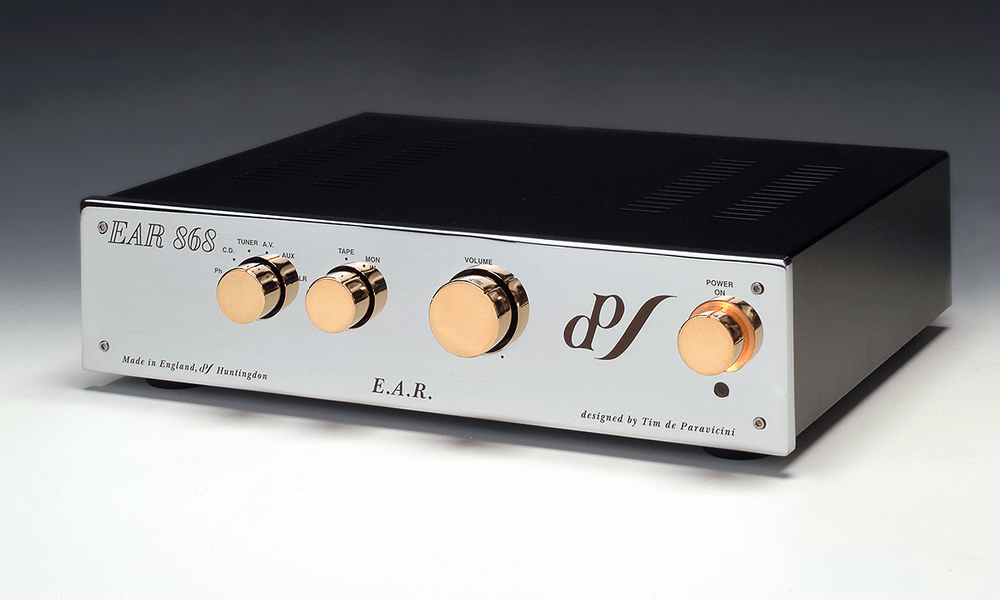

How do you encapsulate a life like Tim’s? He started out building rock and roll amplifiers for bands in South Africa (the Flames – who turned out Blondie Chaplin and Rikki Fataar, later to join the Beach Boys – were early clients). His knowledge grew until he built every single component in the recording and playback chain. He didn’t distinguish between consumer gear and professional gear – for him, it was all electronics, and he knew it all backwards and forwards.

He had a reputation for building exceptional transformer-coupled tubed equipment (on both ends, for both pro and home audio), but I recall visiting him at his home in England 28 years ago, and he was equally proud of his single-transistor amp. A single transistor – atop a maybe 6- or 8-inch pole – just for the look of it. Not many of us have had a chance to hear his 78 RPM turntable, or his multi-way speaker – but trust me, both were stunning. He didn’t overcharge, and often undercharged for his creations, but he knew what he had – and charged for the work that went into them.

And have you ever heard the magnetically-coupled EAR Disc Master turntable? No, because it’s really silent – so much so that it redefined turntable silence – it has no sound of it’s own. Its platter floated above a ¾-inch gap, created by magnets on each side of the platter. After I heard it, I couldn’t wait until I dragged the now-deceased turntable master Brooks Berdan to another listening session with me. And Brooks was appropriately stunned.

Tim would pursue any idea that he thought was interesting, and when he thought he had a product, he’d create the most interesting design to complete it.

I never met his mastering-gear clientele like John Dent (of the Exchange mastering studios in London), but he was another acolyte. (Sadly, he passed away in 2018.)

I met Tim de Paravicini in January of 1990 at Winter CES. As soon as he realized I was a musician, no one else existed. He wanted to tell me about his recording gear, and for about a decade I became the US importer of his professional line of equipment. In 1998 I brought him over to the AES show/conference in San Francisco, along with my 1-inch, 2-track tape deck and a selection of masters from Sheryl Crow (who’s Tuesday Night Music Club album was mixed to one of Tim’s machines), Kevin Gilbert and Altarus Records.

But Tim was a wild man. You didn’t want to cross him, or publicly disagree with him, unless you were equally stubborn (and they’re out there…). And he had a bit of a lack of control-of-himself issue, as anyone who did disagree with him found out. My friend, audio industry veteran and former Copper editor Bill Leebens just called, and reminded me of an audio show a few years back which featured a seminar with Paul McGowan, Arnie Nudell and Tim, among others. Tim was so unhappy with his voice through the PA that was provided that he just got rid of his mic and shouted. Such was the Baron de Paravacini.

And he really was a Baron, a title passed down, in proper English style, from ancestors who gave all their money (unwillingly) to Oliver Cromwell. The de Paravacinis are still owed quite a bit.