Jorma Kaukonen has been wowing live audiences for decades with his remarkable guitar skills and his unique take on American roots music, blues, Americana, and of course rock and roll. As a founding member of two legendary bands, Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna, Jorma has made a musical mark that is revered as widely among his peers as it is among his fiercely loyal fan following.

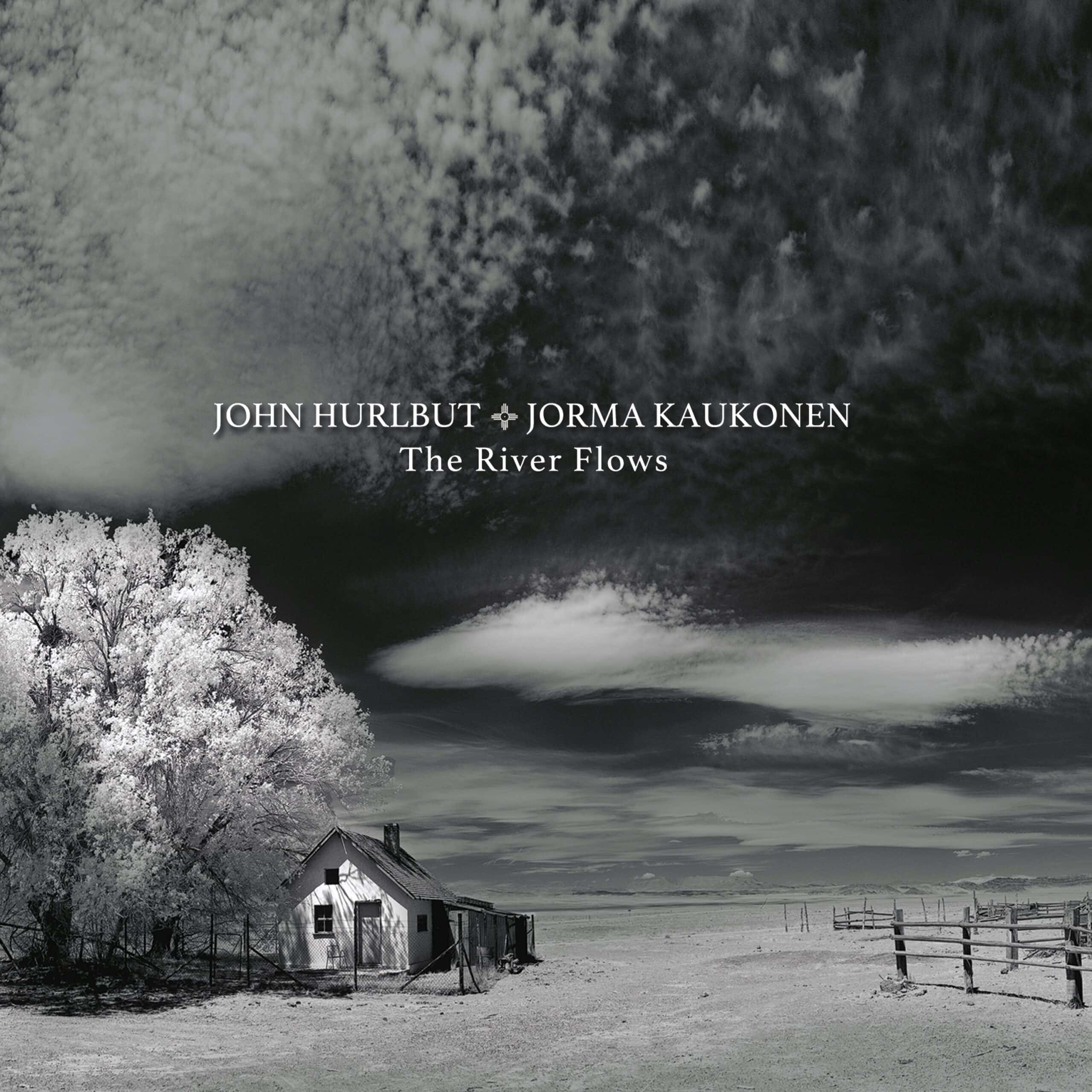

During quarantine Jorma has been hosting a weekly free concert from his Fur Peace Ranch on its YouTube channel. The New York Times recently said it was among the top online concerts launched during COVID-19. Out of these sessions has come the inspiration behind a new record, The River Flows, tied to his long-standing collaborations with John Hurlbut. The River Flows was produced by Jorma at the ranch in Meigs County, Ohio and mixed by three-time Grammy winner and Hot Tuna drummer Justin Guip. Together they have made a record filled with fantastic takes on songs made famous by artists they admire, along with a few originals. It’s a celebration of great music, tremendous acoustic guitar work, and a close friendship that began almost 40 years ago.

The record provided a rare moment where Jorma could step back and allow John to take charge of the music. This shift afforded Jorma the opportunity to just focus on his guitar contributions and put forward some really tasty leads that makes these songs sparkle. As he shared with us, this was arguably the first time he has had that kind of artistic freedom since leaving the Jefferson Airplane in 1972.

We caught up with Jorma and talked about the making of the record, the impact of his YouTube concerts, his life-long friendship with Jack Casady, the birth of his signature Martin guitar, and his now infamous relationship with Janis Joplin. We also had a chance to hear about what is coming next when the current touring ban is lifted.

Ray Chelstowski: The New York Times rated your YouTube series Live from the Fur Peace Ranch as a Top 10 COVID-19 webcast series. How did you approach the project?

Jorma Kaukonen: We’ve been doing this since the first week of April. What we have here at the Fur Peace Ranch is a 230-seat theater and a video production facility because we tape performances for our local NPR station; so we had the infrastructure. As soon as it became apparent that I wasn’t going to be touring and that the Ranch probably wasn’t going to be opening for a while then it became like a Judy Garland thing, “let’s do a show!” Except we didn’t have to go to somebody’s barn. We had it all right here and everything sort of evolved from there.

Now as soon as we started doing this the sharks smelled blood in the water. They were like, “we can do this and monetize that,” and I went, “every time I get involved with one of these streaming services to monetize something it never works.” We decided to instead just do these ourselves and put it out for free. In the end we got so many donations that I was able to pay the production staff for the entire time that we’ve been doing this. It just came about because it gave us something to do and reaffirm my identity as a guitar player. One thing led to another and it’s really become an important part of our lives. We got a lot of positive feedback from people and I give it back to them. This gives us a reason to do what we do. So it’s a team effort and we’re thrilled.

RC: You seem to be enjoying building the set lists and playing songs from throughout your career.

JK: So, one of the other things that it’s given me is the opportunity to go back and revisit old stuff and to practice guitar, because performing live isn’t practicing. That’s a different thing all together. I started to rediscover things that I could still relate to that I hadn’t played in a long time. That’s been a really interesting part of the challenge and has also been rewarding in a lot of ways.

Jorma Kaukonen and John Hurlbut. Photo credit: Scotty Hall.

Jorma Kaukonen and John Hurlbut. Photo credit: Scotty Hall.

RC: This process must have been very freeing.

JK: Yeah absolutely! The other thing that the players out there will understand is that when Jack [Casady] and I are doing what it is that we do we’re really good at it. But since I haven’t had a show to take on the road I’ve had the chance to take some time re-examining some old paths that I haven’t walked on in decades. And that has been rewarding. The other thing is that since the quarantine shows happen to be 90 minutes long, we end up gabbing, so you don’t have to pack it up with songs. I’m spending a lot of time through the week working on songs for the next show, and that’s something I wouldn’t be doing if I was on the road.

RC: So you say that the YouTube series has you practicing guitar even more. Some guys like Jeff Beck leave guitars throughout their house so they can’t avoid practicing. Others like Jonny Lang don’t pick up the guitar until they are ready to head back out on the road. What’s your practice regime like?

JK: Well first of all I have two dogs and a teenage daughter so I don’t leave guitars sitting out. The other thing is that even if it weren’t for the potential guitar disasters I have never been a guy who leaves a guitar out. But the case is never far away. Now I don’t know much about what Jonny Lang would do when he’s not working. And even though me and the guys do electric gigs, I almost never pick up an electric guitar except when we are getting ready to go on tour. So I can really relate to Jonny. But there’s never a day that goes by where I don’t spend a considerable amount of time with my acoustic guitar. I know that a lot of my buddies that primarily play electric guitar don’t agree, but for me that’s where the noose lies. Playing electric guitar is fun to play with the guys, not fun by myself.

RC: Bruce Cockburn has told me that his practicing is now focused on those areas of his playing that have been most impacted by age. Do you use practice in a similar way?

JK: I totally agree with Bruce on that. That’s just a fact of life. Teresa Williams, [musician] Larry Campbell’s wife, is a great singer (great guitar player too in her own right) and has done some vocal workshops for us. One of the things she said that really resonated with me was that as an artist when you’re young you’re bustin’ your ass to learn your craft. Then the train gets rolling, and in your middle years, because you’re still kind of a badass you can coast for a while. Then in the later part of your life as things get physically harder to do you need to practice again just like when you were younger.

I’m very fortunate that even though I’ve had some changes in my hands I have very little arthritis. But there are some things that are more difficult for me to do. I may practice hard-to-do things, but in a performance situation I am going to focus on the things that I know I can execute cleanly, because tone and cleanliness has always been really important to me.

RC: It’s been said that the new record was inspired by your almost 40-year friendship with John Hurlbut. What were you both trying to achieve with these songs and this acoustic approach?

JK: Johnny and I have been have known each other long time and have played together this way for a number of years. At the ranch over the last decade we’ve done performances where I’d say, “throw a song at me and let’s see what happens,” But as I’ve gotten to know his music better, I’ve seen that he has a purity of intent that as an artist I think is somewhat rare. He has no pretensions. He just loves what it is that he does. We’ve spent so much time together that I’ve learned to read him really well and I just thought that Johnny and I needed to do a record.

The Culture Factory got involved and they picked it up immediately. Then we got our buddy Justin Guip, who’s the drummer in electric Hot Tuna, to produce the album and we cut all songs in just two days. There’s no movie magic, there’s no digital editing, there’s no fixing. We just got the performance we wanted and that was important to me. I’m not critical of “brick laying” [overdubbing] with music. We’ve all done it. I just wanted the music to speak for itself.

To accompany someone else in the same kind of head space that I would have used when I was in Jefferson Airplane was utterly liberating in a really profound way. When I do my own thing or play with Hot Tuna I’m doing my thing. But to play with other people where the burden of the song isn’t on me is so liberating that it allows me to do some creative stuff that I probably wouldn’t have done with Hot Tuna.

RC: On the record you include songs by Curtis Mayfield, Ry Cooder, The Byrds, and Dillard & Clark. But the record has a real John Prine vibe to it. When he passed you and John did a tribute to Prine, correct?

JK: Yeah, we did “Angel from Montgomery.” John and I shared a dressing room when we did the “Love For Levon [Helm]” benefit and I had talked about getting him to the ranch. The storytelling frame of mind that John had, or that Guy Clark had, for example, helped create songs that are popular but they’re not pop songs, they just allow you to look into someone’s heart. Every one of those songs that’s on the record is part of a story that I can relate to in a really personal way. But as far as picking the songs, that’s all Johnny.

RC: You have collaborated with many great guitarists. Larry Campbell, G.E. Smith, and Warren Haynes quickly come to mind. What do you look for when picking someone to work with?

JK: I’m not a studio musician and not looking for guitar virtuosity. What I’m looking for is someone who can tell the story in a solid way. When Johnny plays, he’s not an unsophisticated guitar player. His approach is very minimalistic. I think what he was doing was exactly what those songs needed. As a guitar player there are certain common ways we do stuff depending upon your style. Johnny plays with a flat pick and the way he holds it is so bizarre. It’s not like seeing someone with seven fingers (laughs). But it is different and it works.

I kind of take issue with the term “cover a song.” When I was young we didn’t think about writing songs, we just learned songs we liked. To me, covering a song implies doing a song the way the original artists did. Johnny doesn’t do that. He has a song that he likes and it becomes his!

RC: How does someone you collaborate with become part of the staff at the Fur Peace Ranch?

JK: That’s a little bit different. Warren Haynes is arguably one of the greatest living guitar players. He’s also a fantastic singer. Most of us are used to hearing him in an electric format. When he came to the ranch he was teaching an electric class but when he did his show he did it acoustically. When we have guests like Warren the stage is his. Whatever he wants to do is great. If one of our guests wants me to play and they have a place for it I’m happy to do so. If it doesn’t fit into their show I’m happy to step back and listen.

RC: You grew up all over the world. Did that have an impact on the music you’ve made?

JK: I would guess. I’m from the [Washington] DC area, that’s my hometown. Everything that touches our life influences us in some way. Growing up we lived in Pakistan and Pebble Beach; I lived all over the place. I don’t think as I got into music that I set out to make that part of it, but our environment changes us. The fact that I listened to all of those different kinds of sounds no doubt influenced me in some way.

RC: How has your relationship with Jack Casady evolved over time?

JK: We read each other really well because we’ve spent so much time together. I think one of the things that’s really affected our interaction profoundly is that even as kids we always respected each other as people and as artists. We’re really different guys but we’ve never had a band meeting, we don’t argue about stuff, we just always put the art first. And, we listen to each other.

Jack Casady and Jorma Kaukonen, 2009. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Thom C.

Jack Casady and Jorma Kaukonen, 2009. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Thom C.

RC: Tell us about your signature Martin guitar.

JK: I’m not a guitar designer and my life has been dedicated to not trying to over think stuff. Like I don’t know the [scale length] of my guitar; it’s not something that’s important to me. I do know that Martin guitars are long-scale guitars and my Gibsons are short-scale. What the actual dimensions are I don’t know. When I started out playing I got a 1958 Gibson J-50 which I still own. That became the soundtrack of my life for many years. If I’d had money I probably would have gotten a Martin because it’s a fancier guitar. One of my snottier friends in L.A. said, “well you know Jorma, a Martin guitar is a guitar that’s has been to music school!“ There’s a certain cachet about Martin guitars but I couldn’t afford one so I got a Gibson. In the 2000s when Martin was doing artist’s models [David] Bromberg got one. I was doing a show with him in the Philly area and I played his guitar. To make a long story short, I knew the guys at Martin and they gave me a decent deal on a Bromberg signature guitar, which was a 4O [OOOO]-sized guitar with normal Martin [scale length]. I started playing the guitar and just loved it. I felt ritzy.

Later I was approached by Martin about doing a signature guitar and I told them I wasn’t a guitar designer; that I know what I want when I see it. I got involved with a tour and I had to fly to Boston. I had my Bromberg guitar and even though it was in a flight case it got a hairline crack up by the peghead. So I sent it back to Martin to repair it and they sent me a similar guitar called an M5. It was much sparser in terms of its appointments than the 4-0. It wasn’t quite as thick body-wise, which is important to guys like us who play plugged in all of the time. I really loved everything about it and decided that I was ready to talk to Martin about the signature guitar thing. So we went to [the Martin factory in] Nazareth and we stopped at the pizza place across the street from the Martin guitar factory and we designed the Jorma guitar on a napkin. I said that I pretty much wanted it to be like this M5 guitar but we could use Style 30 appointments and we did some fancy stuff around the sound hole.

RC: This year there is quite a lot planned to celebrate the life of Janis Joplin. Can you tell us a bit about The Typewriter Tape recording you did with her in 1964?

JK: I wound up meeting Janis the first weekend I was in the Bay area; we met down in San Jose. As soon as I heard her sing I realized that I was in the presence of greatness. I mean, keep in mind that I was only like 21 years old but I [had] just never heard anything like that. I had listened to Bessie Smith and others but this was one of my contemporaries and she was just as good as any of them. At the time she was living in San Francisco and I was living in Santa Clara. None of us had cars so even being 50 miles away from each other might take the entire day on a bus to get together. So whenever Janis would come down for a gig she would hop on a bus. She had a gig at The Coffee Gallery which was up on Grant Street.

She came down to rehearse and my first wife (may she rest in peace) was writing letters home. We taped everything in those days because I had just gotten a tape recorder and that was a big deal back then. So we fired the recorder up and my ex was typing a letter home and Janis and I were playing. What’s so funny is that people ask if we realized that what we were doing would become something so iconic. Of course we didn’t. It’s just a raw version of Janis at that time. Now I’ve gotten to know Janis’s sister casually over the years and she told me that Jani was constantly reinventing herself. Most everyone knows Janis the rock star. The Janis I knew during that period of time was Janis the blues singer. As time went on she became someone else and that’s OK. But she remains maybe the greatest blues singer I’ve ever played with.

RC: What are your plans for when touring opens up again?

JK: We are going to keep the quarantine concerts going for as long as we can. We’re even talking about pre-recording some so we can do it when I [resume] touring. But for guys like me there’s nothing like that feeling of a live audience and the energy that you get back from them.