John Meyer is a legendary pioneer in the field of sound reinforcement. Many of you have heard Meyer’s gear without knowing it – Meyer Sound equipment is the choice of professionals from arena rock artists like Metallica and Ed Sheeran, touring productions like Cirque de Soleil, concert halls, and theaters of all sizes and configurations around the globe.

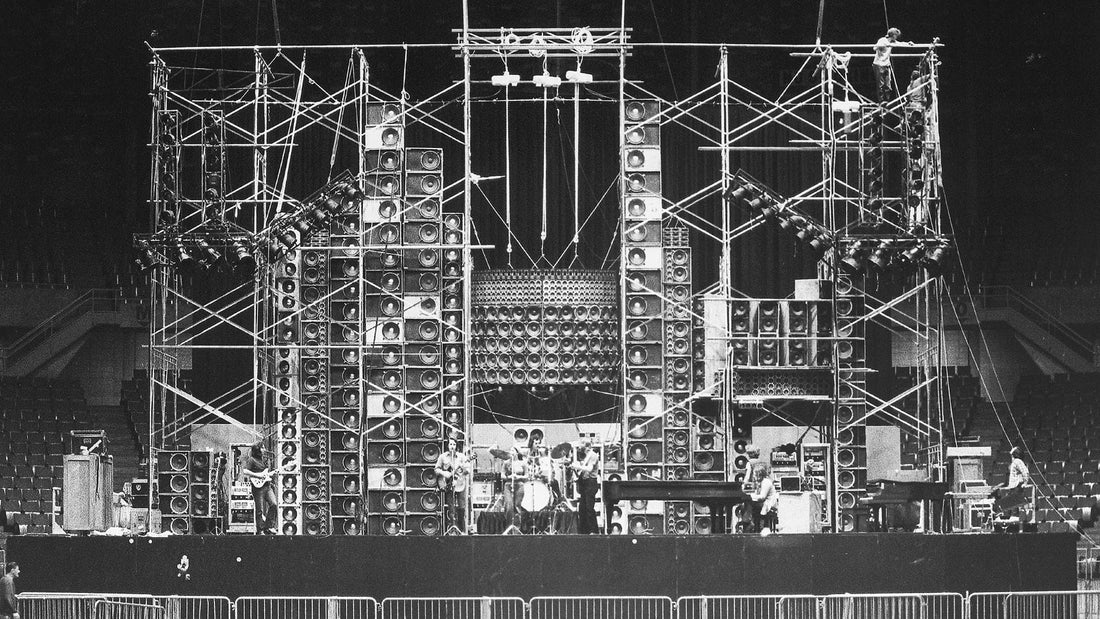

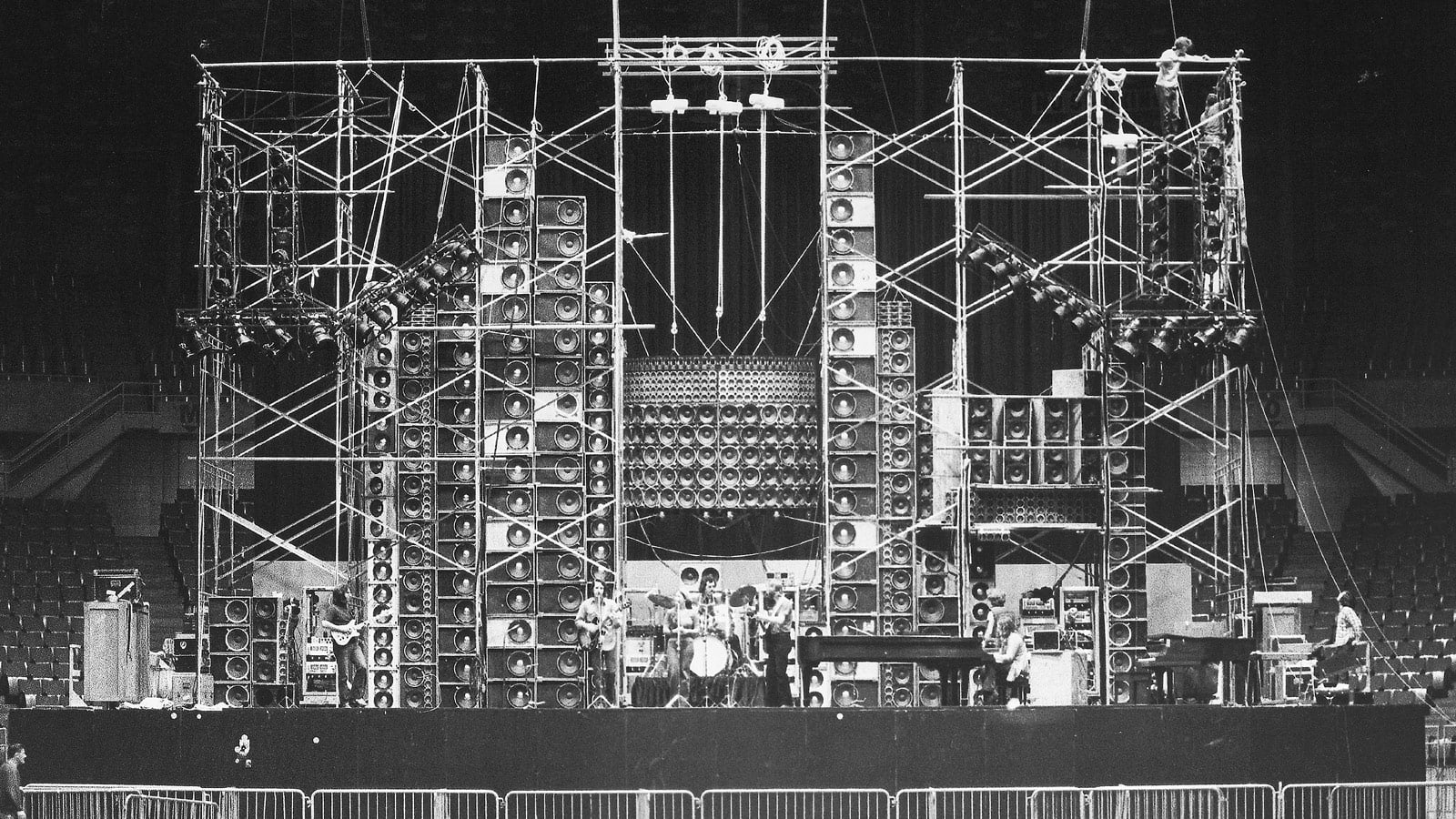

Beginning his professional career when he designed an amplification system for the Steve Miller Band that was used at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, John Meyer went on to work with the Grateful Dead on their legendary (and never duplicated “Wall of Sound,” and he’s amassed a truckload of patents as he pursued linear sound reproduction amplification and loudspeaker systems for live performances. He would even design customized subwoofers for Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios in order to reproduce the ultra-low end frequencies required for screenings of Apocalypse Now.

Founding Meyer Sound Labs in 1979, with his wife, Helen, John Meyer has continued refining and engineering new milestones in audio, incorporating technology and concepts from such disparate sources as military aerospace, chemistry, and materials design. The company is celebrating its 40th Anniversary with groundbreaking new loudspeakers that were showcased in recent demonstrations at AES NYC and have already surpassed sales expectations with their increased bandwidth, improved headroom, versatile application, and reduced price points. John Meyer graciously took the time to share some of his insights with me.

John and Helen Meyer in 1979.

John Seetoo: I understand your audio roots are in radio and film – your stepdad was a radio anchor and an uncle was a sound technician for Disney. Did that early exposure set your direction at a young age, or did you develop your affinity for audio on your own?

John Meyer: Yes, my uncle was doing sound for Disney. I saw his work when I was a kid, on “The Mickey Mouse Club” with the Mouseketeers, things like that. Also. there was a radio station in Berkeley – it’s still there – called KPFA, an FM station which was doing very high quality work when I was a kid in terms of live broadcasts, binaural broadcasts and things like that. So, I got interested in technology and earned my second class radio operator’s license, which allowed me to be much more technically adept. And so, from age 12 on I was really interested in sound. I even had my own program on KPFA called “Sampson Snails,” where I told fairytales from memory. That lasted about a year.

JS: Is it true that your first date with wife Helen was a trip to a hi-fi store to listen to the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album? What made you think it would make for a good first date experience, and did you already foresee her becoming your partner in building Meyer Sound?

JM: I had met Helen when she was a neighbor in Berkeley in 1967. I brought her the new Sgt. Pepper album but she only had a tiny record player that sounded awful. I brought her to the hi-fi shop so she could hear it properly. At this stage, Meyer Sound was still 12 years away, but we were discovering much of the new live music scene together. I realized I needed to find a way for the audience to have a quality sonic experience. We went on to solving many of the challenges in live sound and also continued as life partners and business partners from that Summer of Love in 1967 on.

JS: Given your experience in building the Grateful Dead’s “Wall of Sound” with McIntosh power amps and in other more traditional installations utilizing passive loudspeakers and horns, what prompted you to come up with and focus your designs on self-powered speakers?

JM: The amplifier is a very important part of a sound system. It literally is as critical as the speakers, and the two interact with each other. It’s very difficult when you buy from a third party, from a vendor that’s making only amplifiers, to get the kind of amplifier you need for the speaker you want to use. It was a big challenge during the hi-fi revolution in the fifties and sixties. And it got harder and harder going forward as the manufacturers for the home hi-fi market disappeared. It became clear that if we wanted to build high quality, great sounding speakers, we needed high-quality amplifiers. So, it became a priority that we were going to have to integrate all this together. Designing and building self-powered connects all the engineering teams, the mechanical engineering and the electronic engineering people, so they work together to optimize the balance between the amplifier and the speakers. And you can modify either one to take advantage. It’s kind of like cars were in the old days. You used to be able to buy a lot of parts for your cars. You could get this kind of transmission or that kind, but slowly, the car makers became less interested in having people change out things like that. It’s just not efficient.

JS: Due to SPL and performance space configuration differences between theatrical productions and rock concerts, how did you arrive at your designs for the UPA-1 and other Meyer Sound loudspeaker innovations and what considerations went into the progression to the latest models like the Ultra X-40? Was it merely continuing improvements in greater handling power, lighter weight and reduced price points, or have new factors entered into the equation?

JM: Well, what really matters is that during the hi-fi revolution in the fifties and sixties, mostly in the fifties, the idea was that you’d buy a particular kind of speaker, the kind of speaker you might find more suited for jazz, or another for rock and roll. But that makes it difficult because when working for the rental companies, they’d have some speakers for doing classical stuff, some speakers for doing jazz, some speakers for doing somebody like Elvis Presley. And the idea I got was, if we made the speakers what we call linear, meaning that they’re very transparent, you could use the same system for all genres.

A good linearity example in optics would be something that would record nature and record pop art, and do it all the same. You wouldn’t need a special camera for everything you want to shoot. So when we started working on the UPA, it was one of the first products that we really wanted to be truly universal, so you could use it for jazz, rock and roll and Broadway shows. We wanted to break that barrier and show that this could be solved. It would be much cheaper for a rental company to have one system that they can add to or subtract from, rather than having all of these different kinds of loudspeaker categories. So it became really part of the model, showing the practicality of linear theory. The ULTRA-X40, of course, is the new version of the UPA with everything we’ve learned. It’s kind of like a studio monitor in a practical road package that you can do shows with. It’s evolved that way.

JS: Linear sound is a goal that Meyer Sound Labs’ reputation has been successful at delivering for decades. The acoustic scientific theory and engineering design that needed to be drawn to achieve linear sound must have been a challenge. One curious aspect of one of your designs involved using ultra-low distortion drivers while incorporating intentional pre-distortion of a signal to ensure linear response. Can you explain how this principle works and how you arrived at it?

JM: I think we answered that in a previous question.

JS: Most people involved with sound reinforcement systems design would intuitively create a system with excellent sound for a small venue and then scale it up for larger spaces. If I understand correctly, you work in the opposite direction: you build mammoth systems for excellent sound in stadiums and then modularly break down the arrays to smaller components to accommodate smaller spaces. Can you explain how you developed this methodology and what elements need to be factored into the size reduction of your systems?

JM: When we first started working with the Grateful Dead, at the same time we built a big reinforcement system for a stadium in Oakland for announcements and prerecorded music playback. Then we made a modular section of that system so that we could then build up to a big system. So you want to make sure that the big system will work when you put it all together. A lot of companies would put these big speaker clusters together and then they would not work well when the installation was completely done. You want to make sure that if you’re selling someone the idea that you can buy a few of these speakers and keep adding to them to do bigger shows, you want to know it will perform as planned.

The legendary 1972 Grateful Dead “Wall of Sound.” Photo courtesy of Richard Pechner/rpechner.com

With the Grateful Dead, when we were first starting with the band, I said you could buy more and more of the units over time and then eventually if you do a stadium, you could bring them all together. In fact, when the Dead really did the big stadiums, they knew Frank Zappa had our systems, and they combined them together, which was a really new idea at the time and showed that you could then do really big shows with good sound reinforcement. It was based on the fact that you don’t want to disappoint the band or run into problems, which unfortunately still happens today. You hear out there about people trying things at shows and then they don’t work.

I don’t like to experiment in front of the customer. That’s really risky. This is their livelihood. I mean, we’re technical people. We’re on the sidelines, but they’re on the stage. It’s their show. If something goes wrong, they take the full blame, from the press, the audience, everyone. So you don’t want to disappoint them.

Part 2 of this interview will appear in Copper Issue 100.